![]()

Pre Production

The pre production stage is the first stage of any programme. This is when the planning and preparation that is needed to actually make the programme is done.

Pre production is very important and will usually take up nearly three quarters of the total time between getting a request to make a programme and its final delivery to the client.

This is the time that will need all your communication and management skills. Apart from designing and writing the programme you will have to meet people, negotiate with them, look after them, plan every last detail of the actual shooting and editing and be able to work out budgets and costs so that you offer a fair product for a fair price and make a fair profit.

Every time you go through this process it will get easier and more familiar. Your course will probably allow for this by asking you to write treatments, storyboards, scripts and so on as you practice making programmes. Eventually you will have to go to a client, take the brief and do all the planning yourself.

There are people in the industry who find this side of a production so absorbing and challenging that they make it their career. They are production managers and producers. They are responsible for the production rather than the shooting of it, which is left to the director and crew.

If you eventually intend to start your own production company you will need to become very skilled in this area, or be prepared to employ someone who is, unless you are going to produce small scale corporate type programmes which you can produce and direct. Two important jobs does mean two workloads but won’t necessarily mean two salaries!

If you have read the section called ‘An outline of our production’ you will see that two people run Ace Productions. Elaine looks after the clients and writes and directs the programme, while Simon looks after the management side and is responsible for bookings, logs and locations. It is one of their programmes that we will now follow.

There is no one way that a request for a programme will arrive. You could receive a phone call, a letter or fax, a personal approach or you could reply to a tender request in a trade paper. We will look at examples of phone and letter requests.

The Request for a Programme – By Phone

Phone calls are probably the most difficult to deal with because you will have to think on your feet, take notes, be very careful what you say and sound professional all at the same time.

Imagine this telephone conversation and see how many mistakes you can spot.

The phone rings and you pick it up:

‘Hello’

‘Is that Telly Productions?’

‘Yeah. Who wants to know?’

‘This is Jean Bright, marketing manager of Toys for All; we are looking for a promotional video. Is that the sort of thing you do?’

‘Yeah, all the time, and we won’t charge you an arm and a leg.’

‘Could we meet and discuss some details and prices?’

‘We’re pretty busy at the moment but if you want to pop in sometime tomorrow I can probably spare a couple of minutes. Or, better still, I am always in the Rose and Crown for lunch so I could see you there and buy you a beer.’

‘I have got a busy schedule at the moment, and some other phone calls to make, so perhaps I will ring you back.’

‘OK but make it first thing in the morning next time.’

You are right. Jean Bright did not ring back, or go to the Rose and Crown, and Telly Productions are still looking for their first job.

Often the really silly examples are the best because you know you wouldn’t respond like that. But what about the mistakes?

Always answer the phone in a professional manner. The company and your name should be part of the response. ‘Telly Productions, Pat speaking, how can I help?’ suggests a professional organization. This is a very important first contact.

Be honest. If you have done a promotional video before say so, but do not ‘name drop’, clients are looking for confidentiality and to be told that you have done a promotional video for their biggest rival is not going to help. A simple ‘Yes we have done promotional videos for other organizations’ is enough. If you haven’t, don’t say ‘No never, but we are always willing to give it a try’. Far better to say ‘We have done similar programmes, yes’.

Don’t ever refer to the cost, even if asked. You cannot put a price on a programme you know nothing about. Only if asked directly be honest and professional. ‘It would be unfair to both of us to put a price on anything until we have discussed your exact requirements. You will, however find our prices very competitive.’

If you are asked to meet and discuss it, there are two ways of dealing with this. Neither is right or wrong, just different. The first way involves you saying something like ‘Let’s get our diaries together, have you got a preferred day?’ Having sorted out a mutually convenient day the next problem is to sort out where. This is not as straightforward as it might appear. If, for example, you are working in your back bedroom, you hardly want clients there on a first visit do you? If you have an office, offer it as a second choice, so it is either ‘Could you warn security that I will be coming to see you?’ or ‘Shall I come to you or would you prefer to see our facilities here?’

The second way is arguably more professional and probably more time constructive. Don’t arrange to meet until you have something to discuss. How about ‘Perhaps it would be more constructive if you could send me some details of what you have in mind, then we could arrange to meet and discuss them?’ If you have even a rough idea of what is wanted it will be easier to guess a price range if asked.

Always ask for an address and contact number and remember to say thank you. So ‘Thank you for calling us. Could I take an address and contact phone number, please?’ will end your professional call and you will know that the potential client already has a positive image of your company. This is very important because, even if you do not get this job, Jean Bright might be impressed enough to offer your name to other potential clients that she talks to.

One final important point: you spend a lot of money on advertising to get the work in the first place. It is very helpful to know which adverts work and which don’t. Always ask how clients heard of you. Again there are no fixed rules about when you ask. The rule is ask nicely, ‘How did you get our number then?’ just won’t do! ‘May I ask how you found out about us?’ is about right.

All of this conversation, with names, addresses and any details must be written down. It is the first page of your production diary, under the heading ‘Requests for programmes.’ Even if you never hear any more from Jean Bright, she, and her company, are a useful contact when you send out your next mail shot.

The Request for a Programme – By Letter

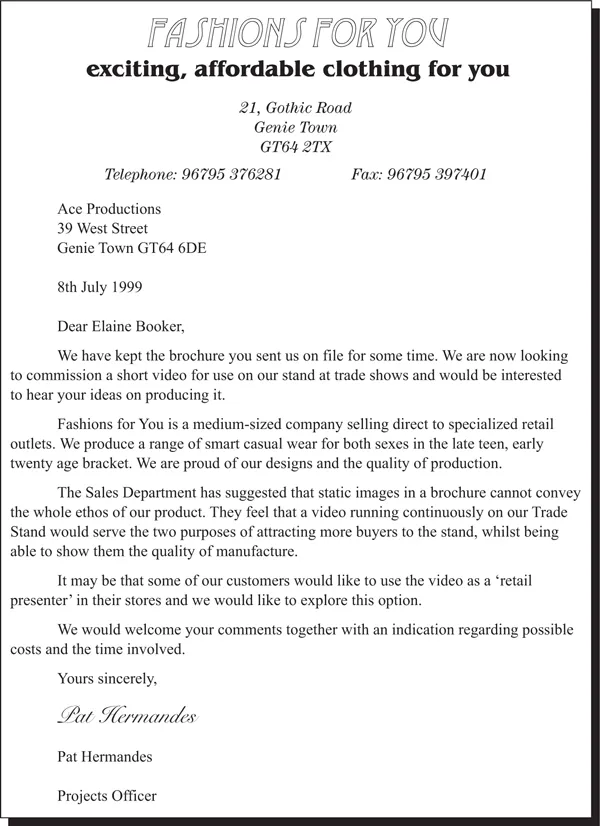

Look at this letter that has been received from Fashions for You. The first thing is to read it more than once so that you understand it, then ask some questions: What is it asking for? Is it a request for information? What information? Is it a request for a programme to be made? Is it a request for a meeting? How are you going to reply? By letter or phone?

The list of questions is almost endless. Two things depend on how you answer this letter. One is whether we get a programme to make, the other is whether I can write the rest of this book because this is the letter that Ace Productions got and upon which this book is based. Fashions for You and Ace Productions are relying on you!

What we need to do is learn as much as possible about what is being asked and, perhaps more important, what we are not being told. Let’s look at the letter in some detail and answer some of the questions. First look at the company logo. Under the name is something called their USP or KSP, this stands for unique selling point or key selling point: ‘exciting, affordable clothing for you’ is their identity of themselves. This is important to you because the programme will have to reflect this. They don’t sell ‘ordinary’ or ‘normal’ clothing; they sell ‘exciting, affordable’ clothing.

Business is about having an identity that makes you stand out from the competition. You will do well to remember exciting and affordable because you will drop these words into conversations with this client at meetings and use them in their programme.

It may be that your course requires you to invent your own company to make your programmes and files more realistic. Give some thought to your logo and USP. Ace Productions’ USP is ‘Video Programmes on Budget & on Time’ and you will see it on their paperwork. It is their identity that separates them from ‘normal’ companies.

The first paragraph is an important answer to the question ‘how did you hear of us?’, it is also a warning. They kept the brochure you sent them. You should keep a note somewhere in your business files showing who you sent mail shots to, when or whether they replied.

Why is it a warning? Think about it, if they kept yours they must have a file of ‘Production companies’. Most companies do, very few use telephone directories. You are not the only video producer in the world; other companies will have got this letter too. This would be normal. What you do next, with your reply, will determine whether you get a meeting. What you do at that meeting will determine whether you get the programme.

The next sentence shows this is a real enquiry, there will be a programme made. They have thought about it and this means they already have an idea about the content. They are intending to ‘commission a short video for use at trade shows’.

The second paragraph tells you who they are, what they do and whom they sell to. It also has another selling point you will use in the programme: they are proud of their designs and quality of productions. This is not a company that produces either rubbish or designer wear, but they do have exciting affordable, quality goods.

The third paragraph tells us how they see the video. This is not going to be a collection of static images; their brochure obviously does that. It wants excitement and movement. It must stop people walking past their stand. It is a sales facilitator type of programme. That means we make a programme showing exciting, affordable, quality clothing designed for the young adult of today, get people to stop and watch it, and then their sales people sell.

The fourth paragraph is not as simple as it seems. The company has obviously seen videos on other trade stands and they have also seen product videos in stores. These two videos are different types, aiming at different audiences. What works for one audience will not necessarily work for another. A compromise won’t work for either. What this paragraph says is that they want the video primarily for their stand, but they would like to explore the possibility of extending it to another audience. They don’t know how it can be done and want to explore the possibility with you. It is a trap. How you deal with this sort of innocent wording is crucial. It will come up again later in the book, so for the moment we will just store it away in our heads.

Our reply to the last paragraph will be the key to getting, or losing, the programme. Do not be tempted to write back and say ‘we do programmes like this all the time. It will be £5000 and will take a week’.

They have asked for an indication of price and time. We cannot do the programme until we have a full brief, we cannot cost it until we know what is involved; what if you find out later that their factory is in the Far East and it will take a week to shoot with six crew? There would not be much left of your £5000, or your week to produce, then would there? This requires some thought and is another trap. We will have to think of something that does not commit us, but does not lose us the programme.

Finally look at the person who sent the letter. Is Pat Hermandes male or female? Does it matter? It would if you decide to reply by phone and ask to speak to Mr Hermandes, only to be told ‘this is Miss Hermandes speaking’.

Look at the job title. What is a projects officer? Not a project manager. Not a marketing manager. Is this someone in an office who has been told to investigate the possibility of a video? Is Pat in charge of the budget? Can Pat make decisions? Is Pat even the client?

At this stage it doesn’t matter. Pat is our only contact. Later, if we get the commission, we will have to find out how much authority Pat actually has. We cannot have a situation where we need a decision now and are then told by Pat Hermandes that it will have to be referred to the procurement committee, which meets once a month.

Finally, we have spent a lot of time looking at, thinking about and developing this letter. All the thoughts, and questions, should have been noted down. Remember that everything goes into the production diary. We will need these immediate thoughts about what this letter says to form part of our reply. We should have not only the letter, but also our thoughts on paper beside us when we compose our reply.

Before we can reply, we need to think about the aims and objectives of this programme.

Aims

It is important to remember that a television programme is an audio and visual experience. This means that the whole thing must be thought out in both sound and picture. Programmes will not work if either is thought of in isolation. It is never a success to try and fit sound to existing pictures or pictures to existing sound. The only exception to this is possibly the pop video where the song exists first, and then pictures are fitted to reflect the mood or theme of the song. Sometimes this works reasonably well, but attempting it is a specialist skill.

The programme must have some sort of aim, without an aim the programme will wander ‘aimlessly’. The aim is an initial idea, often quite vague in nature, along the lines of, for instance, ‘we will do a programme on fashion’. The importance of an aim is that it gives something to focus on, a starting point, we now know the programme will concern itself with promoting stylish clothing. This germ of an idea gives us the concept of the programme that can be stated as an a...