![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

The multicultural dilemma

Michelle Hale Williams

Between October 2010 and February 2011, reigning leaders of major Western countries seemed to declare like falling dominoes that multiculturalism had failed as a strategy of social interpolation of immigrants with their host societies. Beginning with German Chancellor Angela Merkel and continuing with British Prime Minister David Cameron and then French President Nicolas Sarkozy, key speeches marked a turning point. Meanwhile, former leaders of Australia and Spain were coming forward to say the same thing publicly during this period of time (Daily Mail 2011). While American government officials were not joining in overtly, the scholarly critique of multiculturalism in America has been overt since the 1990s (Schlesinger 1992; Taylor 1994; Huntington 2004). Additionally, American politics reflects a growing critique of multiculturalism, whether manifest among mainstream party politicians, social movements such as the Tea Party, political pundits, or more fringe groups such as the American radical right, ranging from white supremacists to militias. The myth of multiculturalism appeared to be unraveling among countries of immigration.

This book considers the contemporary challenge of government in multicultural societies. The action on the part of several world leaders who appear to be giving up on the goal of functional multicultural societies signals a contemporary dilemma among countries with sizable immigrant populations or with increasing rates of immigration over recent decades. In such societies, hostility between the host population and the immigrant population continues to intensify absent the success of multiculturalism. Thus emerges the multicultural dilemma. The widely accepted and politically correct strategy for immigrant absorption, loosely formulated as a call to celebrate diversity while forging common political endeavors has largely produced identity crisis and conflict rather than harmony. Therefore, countries are left to ponder how to constructively manage the nation aspect of the nation-state. Furthermore, to the extent that national unity of purpose (common goals and principles) undergirds and proves an operative principle of democratic government, coping with the multicultural dilemma becomes an urgent priority for countries around the world. This book asks a central question, that is: how can ethnic difference be better understood and mediated by modern nation-states? Focus is on immigration and immigrants and the politics of ethnic identity formation with an assumption that changing patterns of migration precipitate the escalation of obstacles to integration or assimilation.

State strategies for immigrant incorporation

Gary Freeman has articulated four policy strategies employed by nation-states as they confront what he calls “immigrant incorporation” (Freeman 2004). On one extreme, states can choose complete and permanent immigrant exclusion. This typically manifests itself in highly restrictive citizenship laws. For instance, jus sanguinis principles may be operative restricting citizenship applications by hereditary rights. Additionally, a host society may show its disinclination toward the inclusion of immigrants by failure to allow social welfare state benefits to go to immigrants by virtue of their classification as non-citizens.

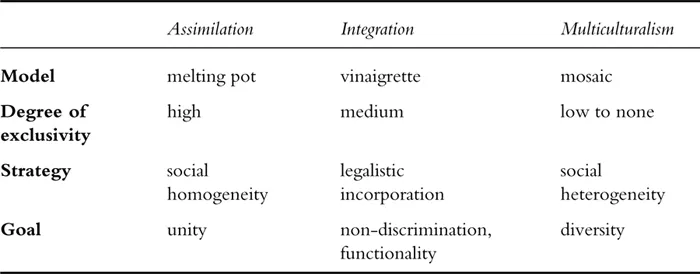

Few modern nation-states opt for complete exclusion, however, and even traditionally jus sanguinis-oriented states seem to be modifying their procedures in recent decades. The next three options are most common in the menu of choice for nation-states (Table 1.1). A slightly more inclusive state strategy than total exclusion permits immigrant incorporation through assimilation. Assimilation requires immigrants to blend in with their new host societies. Beyond assimilation, integration represents an even more inclusive state strategy whereby host societies provide clear legal and procedural channels for immigrant incorporation without requiring that they set aside all differentiating cultural manifestations of their native culture. Finally, multiculturalism offers the most inclusive strategy. It attempts to celebrate diversity while promoting harmonious coexistence. The three strategies with varying degrees of inclusiveness will be discussed in slightly more detailed comparison below.

Table 1.1 Variation in immigrant incorporation strategies

Assimilation is mutually exclusive from multiculturalism. Assimilationist policies require ethnic minorities to become essentially undifferentiable from the host population, embracing its culture and identity along with its language, customs, and traditions. Assimilation models a melting pot with a goal of sameness and unity. Integration presents an intermediate option that is not mutually exclusive of multi-culturalism. Instead, integration approaches multiethnic societies functionally and legalistically requiring equal treatment under the law, equal political access, and equal opportunities, especially those connected with or derived from citizenship. It often requires active steps toward desegregation and the removal of barriers for ethnic minority groups. Integration can be thought of as a vinaigrette, whereby the oil and vinegar separate in the cruet but blend nicely when shaken or on demand. Multiculturalism prefers a cultural mosaic rather than a melting pot within societies. Anthropologist Terence Turner defines multiculturalism saying “Multiculturalism represents a demand for the dissociation (decentering) of the political community and its common social institutions from identification with any one cultural tradition” (1993). It is the idea that multiethnic societies function best when ethnic groups retain their distinctive qualities absent persecution. Furthermore, it requires that each ethnic group receives equal treatment, especially in terms of the law, rights, and access to political resources. It rests upon the premise that ethnic groups that receive fair treatment from the government, through the democratic social contract that organizes such societies, will live together harmoniously in the nation-state. Multiculturalism presents an approach diametrically opposed to that of assimilation in many regards. Its goal is preservation of difference and diversity.

The multicultural experiment

The multicultural experiment appeared to come to a decisive halt in the Western world in late 2010 and early 2011. Speaking as the agenda-setters of their countries, key leaders spoke openly about the division and disharmony in their nation-states between native in-groups and immigrant out-groups. They reflected the frustration of policy-makers who had been trying to make multiculturalism work to no avail. While policies had been put into place to provide for the integration of immigrant communities in their host societies, they described social milieu in which intra-ethnic relations have deteriorated rather than improved. Conveying a political mood of grave concern, these public confessions implied that the rationale of multiculturalism is fundamentally flawed. While institutionalizing integration proved possible from the top down, governments had been unable to bring about the social accord presumed to result from multiculturalism’s preservation of ethnic identity and diversity.

The trend toward constructing multicultural societies spread widely during the mid-twentieth century. As the twentieth century drew to a close, the conventional wisdom had come to favor strategies of multiculturalism across societies rather than assimilationist models (Glazer 1997; Kymlicka 1999; Kymlicka 2001). Several factors contributed to this ubiquitous disposition among states in terms of their approach to citizenship and nation-statehood. First, liberalism predominated as the ideological orientation among advanced industrial societies, as well as among those societies aspiring to such rank. To the extent that the association between lliberalism and pluralism is proven and values such as equality and tolerance, the argument was made that liberalism presupposed multiculturalism. Significant philosophical debate on this issue followed. Anke Schuster (2006) argues against a causal connection, but credits several scholars with the assertion of such a connection including Kymlicka (1995), Taylor (1994), Gutmann (1994), and Parekh (2000). Regardless of the outcome of this debate, the connection between liberalism and multiculturalism seemed to appear in governmental agendas and policy directives worldwide as democracies determined to be more tolerant and inclusive of their pluralism by becoming more multiculturalist in their rhetoric, policy strategies, and approaches.

Another factor driving the pro-multiculturalism disposition common to states through the latter half of the last century was the postwar and postcolonial consensus among states favoring state accommodation of political and economic refugees. By the close of the twentieth century, emphasis was placed on sheltering asylum seekers. Additionally, during this time, economic migrants, or those seeking a better way of life for themselves and for their families (whether or not their families physically accompanied them) were commonplace. The notion prevailed at the time that economic migrants provided a service and a benefit to their host societies taking jobs that their own citizens would not. The “guest worker” concept suggested that economic migrants would come, work to benefit themselves and their host societies, and then return to their host country. However, even if immigrants decided to make their migration permanent, host societies generally retained the notion that they could incorporate these immigrants without great difficulty.

The deliberate and conscientious turn by governments toward building multi-cultural societies appeared pronounced in the last two decades of the twentieth century. The term was reportedly used first by a Canadian Royal Commission in 1965 and was used notably in both Canada and Australia in the 1970s “as the name for a key plank of government policy to assist in the management of ethnic pluralism within the national polity” (Ang 2005, 34). In the United States, the term emerged in the early 1980s in the context of public school reform where school curricula were accused of excessive Eurocentrism. West European usage of the term followed toward the latter half of the 1980s with discussions of minority inclusion among governments occurring widely. In Britain, the 2000 Parekh Report, named for its chairperson, Bhikhu Parekh, had been commissioned as a means of addressing the reconciliation of its growing cultural diversity (Ang 2005). In Germany, the July 2001 report on “Steering Migration and Fostering Integration” was the result of the labor of the Süssmuth Commission, named for chairperson Dr. Rita Süssmuth. This commission had been tasked with examining Germany’s challenge with multikulti, the national buzzword for multiculturalism championed by the progressive left including the German Green Party. Clearly advanced industrial societies were confronting a common dilemma in search of strategies for implementing multiculturalism.

Contemporary nation-states face an imperative of migration policy-making. James Hollifield described the emergence of a “migration state” whereby “regulation of international migration is as important as providing for the security of the state and the economic well being of the citizenry” (2004, 885). In looking across democracies at countries and their policies toward immigrant incorporation, Castles and Miller (2003) classify countries into three categories in terms of their strategies. First, Germany, Austria, and Switzerland with their legacies of jus sanguinis citizenship are classified as differential exclusionist. Second, France, Britain, and the Netherlands comprise a category of assimilationist. Finally, the United States, Canada, Australia, and Sweden exemplify multiculturalism. Criticism of the classification scheme includes the critique that some countries fit multiple categories, underdeveloped theoretical criteria for inclusion, and the inability to place certain countries in any category at all (Freeman 2004). Additionally, static classification proves difficult as policy shifts and adjustments to conditions have been common across countries even prior to the dramatic changes in the autumn of 2010.

One key area for country-specific policy comparison revolves around citizenship and naturalization procedures. The Dutch naturalization policies were characterized for a time as relatively liberal globally in terms of allowing relative ease and little red tape with becoming a Dutch citizen, despite a more recent trend toward greater restrictiveness. The multiculturalist trend in Dutch migration policy is evident given that about 11 per cent of the Dutch population are foreign-born immigrants, yet only 4.5 per cent of the population do not hold a Dutch passport (Entzinger 2006). It is noteworthy here that even countries with traditionally jus sanguinis dispositions have experienced policy reversals in the era of multiculturalism by the end of the twentieth century. The German green card bill captures the change in Germany, as a demographic deficit led to a policy of allowing highly skilled immigrants to come to work with full temporary citizenship rights in fields with specialized labor shortages. It marked a major shift in German migration policy (Hollifield 2004) in the direction of greater multiculturalism.

Another area where migration policy terms vary pertains to economics including transnational trade, investment, and labor. To the extent that “trade and migration go hand in hand” (Hollifield 2004, 903), the increasingly international nature of economics has meant change in migration policy. Emphasis in advanced industrial economies on service sector trade has yielded increased migration of highly skilled workers (Bhagwati 1997). Yet some states allow more free movement of labor migrants, while others restrict this more heavily. Guest workers were commonly supplied to fill working-class labor shortages in economically advanced countries throughout much of the twentieth century. The United States openly recruited Mexican workers in the agricultural sector in the 1940s, although this policy was officially reversed with the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) (Castles 2004). Northwest European states allowed guest workers to migrate and contribute to their postwar reconstruction efforts following the Second World War (Miller and Martin 1982). Australia openly recruited healthy, Caucasian immigrants coming from other British Commonwealth countries in the 1940s to try to increase population size and geopolitical power. Australia was widely considered a rather open country for migration for labor purposes and joined the ranks of other countries recruiting skilled labor at the end of the last century. In sum, demands for labor have been common cross-nationally and context has determined whether more or less skilled workers were in demand at a given time. Generally speaking, the trend has moved from less skilled toward more skilled workers ...