![]()

Part I

INTRODUCTION

![]()

Chapter 1

Analogies, Metaphors, and Images: Vehicles for Mathematical Reasoning

Lyn D. English

Queensland University of Technology

Mathematics … is the study of the structures that we use to understand and reason about our experience—structures that are inherent in our pre-conceptual bodily experience and that we make abstract via metaphor.

—Lakoff, 1987, p. 355

One of the challenges facing research and development in mathematics education is how students mentally structure their mathematical experiences and how they reason with these structures in learning and problem solving (Davis, 1992). Our ideas on what students can learn, on what they should be learning, and on what they should be doing with their learning, depend on our concept of learning itself (Lakoff, 1987).

It is commonly accepted that effective mathematical learning requires active student participation in meaningful experiences which deal “in an accurate and relevant way with important parts of real mathematics” (Davis & Maher, this volume, p. 97). These experiences need to foster the construction of mental models or representations that comprise the important relations and principles of a domain (e.g., English & Halford, 1995; Fuson, 1992; Goldin, 1992; Greeno, 1991; Hiebert & Carpenter, 1992; Sfard, 1994). There has been considerable debate however, on how students construct these mental models, on what forms these models take and how they change with development, and on how students apply these models in different mathematical situations.

Recent developments in cognitive science provide exciting prospects for clarifying these issues. Because cognitive science draws on several disciplines, including psychology, philosophy, computer science, linguistics, and anthropology (Lakoff, 1987), it provides rich scope for addressing issues that are at the core of mathematical learning. The ideas presented in this volume reflect this interdisciplinary cognitive science approach. As such, they represent a move away from the traditional notion of reasoning as primarily propositional, “abstract and disembodied,” to the contemporary view of reasoning as “embodied” and “imaginative” (Lakoff, 1987, p. 368). From this latter perspective, mathematical reasoning entails reasoning with structures that emerge from our bodily experiences as we interact with our environment. These structures extend beyond finitary propositional representations (Johnson, 1987). Mathematical reasoning is imaginative in the sense that it draws upon a number of powerful, illuminating devices that structure these concrete or base level experiences and transform them into models for abstract thought. These “tools to think with” (Davis & Maher, this volume, p. 114) include analogy, metaphor, metonymy, and imagery. To date, insufficient attention has been given to the important role these play in mathematical reasoning.

My purpose in writing this chapter is to introduce the reader to these vehicles of thought, including the important role they play in the conceptual structure of mathematics, and how they can enhance mathematical learning, understanding, and problem solving. I also review briefly the contributions of each author and conclude the chapter with a number of issues for further study.

REASONING WITH ANALOGY

And, I cherish more than anything the Analogies, my most trustworthy masters. They know all the secrets of Nature, and they ought to be the least neglected in Geometry. (Johannes Kepler, cited in Polya, 1954, p. 12)

The human ability to find analogical correspondences is a powerful reasoning mechanism. Indeed, it is considered to be linked intimately to the evolutionary development of our capacity for explicit, systematic thinking (Holyoak & Thagard, 1995). As Holyoak and Thagard so insightfully illustrate, reasoning by analogy impacts on almost all avenues of our lives. For example, we use analogy in everyday problem solving, in decision making in law and politics, in addressing the deep issues of religion and philosophy, and in scientific and mathematical theory building.

Studies have shown that very young children use analogical reasoning under appropriate conditions (e.g., Alexander, White, & Daugherty, this volume; Goswami, 1992; Pierce & Gholson, 1994). There are many ways in which children use such reasoning, including as a source of hypotheses about an unfamiliar situation, as a source of problem-solving operators and techniques, and as an aid to learning and transfer (Halford, 1993). Despite the ubiquity of analogical reasoning, its role in students’ mathematical reasoning and learning has received little attention; this is in contrast to the substantial work that has been conducted in science education (e.g., Clement, 1993; Stavy & Tirosh, 1993) and in psychological studies of problem solving and transfer (e.g., Gentner, 1989; Holyoak, Novick, & Melz, 1994; Novick, 1992).

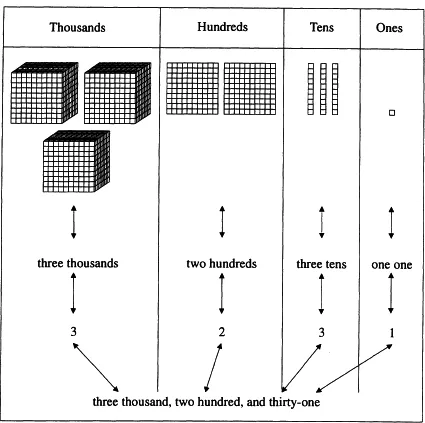

Reasoning by analogy is generally defined as the transfer of structural information from one system, the base, to another system, the target (Gentner, 1983, 1989; Vosniadou, 1989; see also Gholson et al., and English, this volume, for further elaboration). This transfer of knowledge is achieved through matching or mapping processes, which entail finding the relational correspondences between the two systems. It is this emphasis on corresponding relational structures (in contrast to superficial attributional correspondences) that has significant implications for mathematics learning, as can be seen in the chapters of this volume. An obvious example of reasoning by analogy in mathematics learning lies in children’s interpretation of concrete and pictorial/diagrammatic representations. These external representations act as the source for the learning of the target concept, as indicated in the base-ten block representation of the numeral 3231 shown in Fig. 1.1. Children’s manipulative experiences with these concrete materials provide the foundation for their construction of cognitive models of whole number concepts, as I explain in chapter 6.

For children to reason meaningfully with mathematical analogs, they need to understand the structure of the source and must be able to recognize the correspondence between source and target, that is, the mappings to be made should be unambiguous (see English & Halford, 1995, for further discussion). The importance of using analogs that clearly display the intended relational structure supports our earlier argument that mathematical reasoning is embodied, that is, abstract ideas inherit the structure of our physical, bodily, and perceptual experiences. Once children gain confidence in articulating the concept or generality conveyed by the concrete analog, they can begin to make the required “abstraction shift,” where the generality itself becomes the object of thought (Mason, 1989, p. 6); children can now manipulate their mental model of symbolic number.

At this point, it is worth reviewing the notion of mental models as these are fundamental to the mathematical reasoning we are addressing here. The importance of mental models in learning and problem solving has been well documented (e.g., English & Halford, 1995; Gentner & Stevens, 1983; Gholson et al., this volume; Greeno, 1991; Halford, 1993; Johnson-Laird, 1983; Johnson-Laird & Byrne, 1991; Rouse & Morris, 1986). Mental models are considered to provide the workspace for inference and cognitive operations (Halford, 1993), and are generally defined as internal structures that represent external reality, at least in an approximate way. That is, mental models have a similar relational structure to the reality they represent (Glasgow, 1994; Greeno, 1991; Holyoak & Thagard, 1995). Mental models compare with Johnson’s (1987) image-schematic structures that give “order and connectedness to our perceptions and conceptions” (p. 75). These image schemata are revisited later. Because of their relational structure, mental models are particularly important to mathematical reasoning. Indeed, as Johnson (1987) noted, “… there can be no meaning without some form of structure or pattern that establishes relationships” (p. 75). The experiences we provide our students thus need to encourage the development of mental models which comprise the essential relations and principles of a mathematical domain (English, chap. 6, this volume; Sfard, 1994).

FIG. 1.1. Analogical representation of a 4-digit whole number. From English and Halford (1995). Reproduced with permission of Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Both analogy and metaphor are important not only in the initial construction of these mental models but also in their subsequent development and refinement. For example, children’s explorations with tens- and ones- blocks assist them in constructing a basic model of the relationships within two-digit numbers. This mental model then becomes the source for children’s exploration of the relations in multidigit whole numbers (via manipulation of the concrete representation), and subsequently, for their introduction to decimal fraction ideas. Of course, a complete understanding of numeration entails many other relations, effectively developed through analogical reasoning (see e.g., English & Halford, 1995).

In the next section I give brief consideration to metaphorical reasoning, which shares many of the cognitive processes of analogical thinking but also has its own special features (as Anna Sfard demonstrates in her chapter).

REASONING WITH METAPHOR AND METONYMY

Reasoning with metaphors is considered a fundamental way of human thinking and communication, as can be seen in our everyday use of abstract concepts such as time and change (e.g., “Time is money”; “The time for a decision is drawing to a close”; “It suddenly dawned on her that the problem could be solved in a faster way”; Holyoak & Thagard, 1995; Johnson, 1987; Lakoff, 1987, 1994). Contemporary research on metaphorical reasoning interprets the notion of metaphor in a broader sense than the traditional, literary interpretation. That is, the power of a metaphor lies “in the way we conceptualize one mental domain in terms of another”; reasoning metaphorically is thus characterized by cross-domain mappings (Lakoff, 1994, p. 206).

We understand metaphor by finding a mapping between the target domain, that is, the topic of the metaphor, and the source domain (Holyoak & Thagard, 1995). The connection between the two domains however, is usually implicit. Like analogical reasoning, metaphorical reasoning can generate new inferences and lead to the construction of mental models based on the relational structure shared by the source and target. This can change our understanding of both the source and target.

As Lakoff and Núñez (chap. 2) and Sfard (chap. 13) demonstrate, metaphor is central to the structure of mathematics and to our reasoning with mathematical ideas. These authors provide examples of the many instances in which we employ metaphorical reasoning in our own understanding of mathematical ideas and in conveying these ideas to others. As Presmeg (this volume) notes, some metaphors are so much a part of the mathematics curriculum that we may no longer see them as metaphors (e.g., in our reference to an equation as a balance). Metaphorical reasoning can assist students in their interpretation of formal mathematical language which has different meanings from the familiar, everyday connotations. Terms such as, degree, field, function, group, power, root, set, divide, express, and reflect fit this category (van Dormolen, 1991). The use of metaphor is particularly helpful in developing an understanding of abstract mathematical concepts and procedures that are difficult to represent with concrete analogs. For example, we might implicitly compare a function with a vending machine, a vector with an arrow, an equation with a pair of scales, and our number system with points on a line (Matos, 1991; van Dormolen, 1991; see Lakoff & Núñez, this volume, for further examples). These examples involve cross-domain mappings in which the abstract mathematical idea (target), is understood in terms of a concrete, familiar domain (source), which as Lakoff (1994) pointed out, is usually spatial.

These cross-domain mappings are highly structured (Lakoff, 1994), and for the metaphor to be effective, the learner must make the appropriate relational mappings (as with analogies). Consider for example, the use of a line metaphor to represent our number system, that is, numbers are considered as points on a line. The “number line” (see Fig. 1.2) is often used to convey the notion of positive and negative number, to display number sequences and relations (including relations between whole and fractional amounts), and to illustrate simple integer operations.

While this metaphorical representation attempts to link a familiar domain (i.e., a simple line drawing) with abstract mathematical ideas (e.g., between any two rational numbers there are countless other rational numbers), students frequently have difficulty in abstracting these ideas (Dufour-Janvier, Bednarz, & Belanger, 1987). There is the tendency for students to see the number line as a series of “stepping stones,” with each step conceived of as a rock with a hole between each two successive rocks. This may explain why so many students say that there are no numbers, or at the most, one, between two whole numbers. These students are mapping only the clearly visible relations between the source and target domains, that is, they are linking the explicit marks on the line with the integers and ignoring any implicit relations (e.g., relations between whole numbers and fractions, implicit in the space between the marks). Although it can serve as an effective metaphor for our number system, the number line is a complex representation requiring students to integrate two forms of information, namely, visual and symbolic. The symbols can distract the student from any visual embodiment of abstract concepts (Bright, Behr, Post, & Wachsmuth, 1988; Hiebert, Wearne, & Taber, 1991; Larson, 1980).

This last example highlights the need to analyze the complexity of the metaphors and analogs we use with our students. If the intended mathematical relationships are difficult to discern, then the analog or metaphor can become the target of a student’s learning, rather than the source or the vehicle. That is, the student is faced with the problem of interpreting the metaphor itself, before she can even begin to use it in understanding the abstract mathematical concept. It is not surprising then, that students treat the source and target domains as separate entities, failing to see any corresponding relations between the two. This means students’ mathematical reasoning is disembodied from any meaningful experiences, which can account...