![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: RET in the built environment

Background

The Implementing Agreement on Renewable Energy Technology Development of the International Energy Agency (IEA-RETD) has the objective to support a significantly higher utilisation of renewable energy technologies (RET) by encouraging more rapid and efficient deployment of these technologies. RET are increasingly recognised for their potential role within a portfolio of low-carbon and cost-competitive energy technologies capable of responding to the dual challenge of climate change and energy security. Moreover, RET have the potential to reduce environmental pollution caused by fossil fuel-based energy sources.

The building sector presents a large opportunity for reducing CO2 emissions in a cost-effective manner. About 40 per cent of final energy consumption takes place in existing buildings, and buildings account for about 24 per cent of global CO2 emissions.1 At the same time, the building sector offers some of the largest potentials for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions at negative costs. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2007) estimates that globally about 30 per cent of the business-as-usual CO2 emissions in buildings projected for 2020 could be mitigated in a cost-effective way. There is a large potential for meeting the energy demand of buildings by means of district heating and cooling schemes or through the direct use of RET in buildings (IPCC, 2011).

However, as illustrated in previous studies by the IEA (IEA, 2007, 2008a, 2010; IEA-RETD, 2007) and other organisations (e.g. WBCSD, 2010; Wuppertal Institute, 2010; European Commission, 2010/11) various barriers prevent the accelerated uptake of RET and energy efficiency measures in the built environment. New and innovative business models may help to exploit the potential of a sustainable energy in the built environment by addressing one or more of these barriers.

The IEA-RETD therefore commissioned the project ‘Business models for Renewable Energy in the Built Environment (RE-BIZZ)’ to gain insights into the way new business models and/or policy measures can stimulate the deployment of renewable energy technology (RET) and energy efficiency (EE) in the built environment. The project aims at providing recommendations to both policy makers and market actors. This book presents the work undertaken within this project.

Scope of the report

Technological focus, market segments and country focus

The study focuses on business models for increasing the deployment of RET in the built environment. Where necessary, the report also addresses energy efficiency measures and how energy efficiency measures relate to the deployment of renewable energy, as energy efficiency plays an important role in reducing energy use in buildings. In addition, many existing studies, for example on barriers for reducing GHG emissions from buildings, focus on energy efficiency. Previous research commissioned by the IEA-RETD (IEA-RETD, 2010) suggests that the lessons from the promotion of residential energy efficiency may largely be transferred to programmes promoting the residential use of renewable energy.

The analysis covers renewable electricity, and heating and cooling. The following renewable energy technologies in buildings fall under the scope of the study:

•Solar PV (see Figure 1.1)

•Solar thermal for water and space heating (solar boilers) (see Figure 1.2)

•Small-scale wind turbines on the roofs of buildings for electricity generation

•Biomass heating (e.g. wood pellets)

•Heat pumps and small-scale district heating/combined heat and power (CHP) plants based on renewable energy (e.g. when installed by a property developer on a large housing or business complex)

•Heat and cold storage systems

•Micro-CHP systems may be included because, although they are not a RET, a micro-CHP system is generally more efficient than traditional electricity and heat production, and may be based on renewable energy in the future.

EE measures are not an explicit focus of the report. However, where the analysis does refer to EE measures, these could include the following:

•Insulation (wall, roof, floor, window, heating and water pipes, crack sealing)

•Low temperature room heating

•Heating boiler controls

•Heat recovery systems (ventilation system, shower) (see Figure 1.3)

•Other (water saving shower heads, weatherstrips etc.).

Figure 1.1 New houses with roof-mounted solar PV systems in the Netherlands (photo: ECN)

Figure 1.2 Solar thermal water heating system at the University of Michigan (photo: Clean Energy Resource Teams)

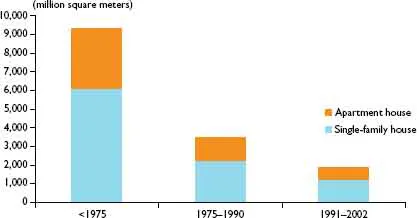

The study distinguishes between the following market segments: new versus existing buildings, owner-occupied versus rented, and commercial versus residential (if needed further split into multi-family dwellings, de/attached homes and stand-alone houses). Within the segment of commercial buildings, where required, the specific role of public building owners is addressed. Deploying RET and EE measures in existing buildings is especially important as in many OECD countries a large part of the housing stock has been constructed before comprehensive building related energy regulations were put in place (see Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.3 Colourful wind cowls which provide passive ventilation with heat recovery at the UK eco-village BedZED, a residential and workspace development in the London borough of Sutton (Photo: telex4)

Some parts of the study include country specific explanations. Case studies from a country or region are used to illustrate the business models. In addition, the business models are put into the context of the country specific regulatory environment. Where this is the case, the IEA-RETD member countries, i.e. Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, United Kingdom, are examined. The study may also refer to other countries and country situations which could be potentially interesting in the long term for the business models evaluated such as, but not limited to, China and the United States.

How to define business models for RET in the built environment

Research on business models originated during the rise of e-commerce and the development of other internet-based companies in the 1990s and early 2000s. Since then, business models have become an increasingly popular concept in management theory and practice. Today, the concept is being applied to an ever wider range of sectors and topics (Wüstenhagen & Boehnke, 2008; Osterwalder, 2004).

Figure 1.4 Age of the housing stock in Europe. About 50 per cent of building space was built before 1975 (WBCSD, 2010)

A large number of studies on the theory of business models exist, but so far there is no generally accepted definition of what a business model is, although the definitions generally state that it describes how a business creates value (Osterwalder, 2004; Osterwalder et al., 2005; Porter, 2001; Schafer et al., 2001). The approach for value creation can then be split into different aspects, including, for example, the strategic objective and value proposition, sources of revenue, critical success factors, core competencies, customer segments, sales channels (Weill and Vitale, 2001, see Table 1.1) and key activities and resources.

Other definitions are simpler, e.g. defining a business model as ‘the method of doing business by which a company can sustain itself, that is, generate revenue’ (Rappa, 2001).

Based on these considerations, we recognise the following distinction between a business case and a business model:

•a business case captures the logic and reasoning for initiating an activity, such as an investment in RET in the built environment. The reasoning includes a financial calculation demonstrating the profitability of the planned investment.

Table 1.1 Elements of a business model according to Weill and Vitale (2001) (adapted from Osterwalder, 2004)

| Element of the business model | Description |

Strategic objective and value proposition | Overall view of the target customers, product and service offering and the unique market position that the firm aims to achieve; defines the choices and trade-off inherent in the firms strategy and operation. |

Sources of revenue | A firm should have a realistic view on revenue sources. |

Critical success factors | In order to make business models successful, the critical structures have to be identified, e.g. by questioning industry assumptions and patterns of established business models. |

Core competencies | In-house competencies that a firm needs to possess to be successful. |

Customer segments | Important to understand which customer segments a firm targets and by what the specific value proposition for each customer segment is. |

Sales channels | The way and approach how a firm's products and services are offered. It is considered part of the firm's value proposition by Weill and Vitale (2001). |

•a business model describes the structure and strategy behind a business case, and includes elements such as value proposition, key activities, key resourc...