- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Psychology of Learning Science

About this book

Focusing on the teaching and learning of science concepts at the elementary and high school levels, this volume bridges the gap between state-of-the-art research and classroom practice in science education. The contributors -- science educators, cognitive scientists, and psychologists -- draw clear connections between theory, research, and instructional application, with the ultimate goal of improving science teachers' effectiveness in the classroom. Toward this end, explicit models, illustrations, and examples drawn from actual science classes are included.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education General1 A Constructive View of Learning Science

Shawn M. Glynn, Russell H. Yeany, and Bruce K. Britton

University of Georgia

If the students of today are to prosper in the 21st century, they must understand the basic facts, principles, and procedures of science. In other words, the students must be scientifically literate.

The world is becoming increasingly technical; science teachers are responsible for preparing students for this technology. Science teachers should emphasize the quality of their students’ learning rather than just the quantity: Conceptual understanding is more important than rote memorization. Science teachers should emphasize the process of science rather than just the content, because students who understand the process are better prepared to acquire science content on their own. Science knowledge changes quickly and the updating of one's knowledge is a lifelong activity.

Conceptually based, process-oriented instruction calls for a lot of hard work on the part of both teachers and students. Teachers and students must actively organize, elaborate, and interpret knowledge, not just repeat it and memorize it.

PSYCHOLOGY OF LEARNING SCIENCE

The psychology of learning science holds the response to the challenge of increasing students’ understanding of science. Throwing more science facts and principles at the students is not the answer. Increasing the number of students’ laboratory activities is not the answer either; a trendy emphasis on “hands on” will not, by itself, increase students’ understanding of science. What is additionally needed is a “minds on” emphasis in the learning of science. For example, high school students should be required to understand what is meant by important concepts in biology (e.g., photosynthesis and mitosis-meiosis), chemistry (e.g., chemical equilibrium and the periodic table), physics (e.g., gravitational potential energy and electromagnetic induction) and earth science (e.g., plate tectonics and precipitation). To test students’ understanding, they should be asked to explain these ideas. When the students’ explanations are not clear, they should be required to clarify them. The students must be able to explain concepts using their own words rather than repeating the words of a textbook author.

Teachers should require students to reason scientifically. One way they can do this is by modeling scientific reasoning for their students. In effect, teachers and students should become collaborators in the process of scientific reasoning. Together, teachers and students should construct interesting questions about science phenomena; simply telling students the answers has little lasting value. Teachers and students should guess, or hypothesize, about the underlying causes of science phenomena. Teachers and students should collect data and design scientific tests of their hypotheses. And finally, teachers and students should construct theories and models to explain the phenomena in question. Throughout all stages of this collaboration, teachers and students should be constantly “thinking out loud” (Glynn, Muth, & Britton, 1990). By means of the “thinking out loud” technique, teachers can help students to reflect on their own scientific reasoning processes (that is, to think metacognitively) and to refine these processes.

TRADITIONAL TEXTBOOKS AND METHODS

Why are teachers not routinely modeling scientific reasoning for their students? To some degree, the fault may lie with traditional textbooks and methods of instruction.

A school science curriculum can be placed on a continuum from “textbook-centered” to “teacher-centered.” In a textbook-centered curriculum, the textbook is the engine that drives the curriculum. A textbook-centered curriculum aspires to be “teacher-proof,” or able to support teachers who may lack important knowledge, training, and experience.

In a teacher-centered curriculum, a textbook may still play an important role, but the teacher has much more control over the methods of instruction. The teacher-centered curriculum assumes that the teacher knows a great deal about science, about methods of instruction, and about the way that children learn and develop.

Currently, the curriculum of the United States tends to be textbook-centered. According to Bill Aldridge (1989, p. 4), executive director of the National Science Teachers Association, “Consider the typical situation in the United States. Children study science in elementary school mainly by reading about it.” U. S. publishers refer to their product as a “program” rather than a textbook, because the “teacher's edition” prescribes precisely how concepts should be taught, and the textbook is accompanied by a host of resource materials, such as videotapes, software, overhead transparencies and masters, laboratory manuals, study guides, test item banks, posters, and motivational activities (e.g., physics fairs, competitions, and conventions).

Unfortunately, the present textbooks and associated methods of instruction are not particularly effective. According to the American Association for the Advancement of Science report, Science for All Americans:

The present science textbooks and methods of instruction, far from helping, often actually impede progress toward scientific literacy. They emphasize the learning of answers more than the exploration of questions, memory at the expense of critical thought, bits and pieces of information instead of understandings in context, recitation over argument, reading in lieu of doing. They fail to encourage students to work together, to share ideas and information freely with each other, or to use modern instruments to extend their intellectual capabilities. (1989, p. 14)

The present science textbooks and methods of instruction do not yet take into account recent discoveries in the psychology of how students learn science. Discoveries about the constructive nature of students’ learning processes, about students’ mental models, and students’ misconceptions have important implications for teachers who wish to model scientific reasoning in an effective fashion for their students. Eventually, these discoveries will have a significant impact on textbooks, methods of instruction, curriculum courses for future science teachers, and in-service workshops for current science teachers. But there is a need for something to be done now to communicate these discoveries to teachers, textbook authors, and college professors who train science teachers. The Psychology of Learning Science was written to address this urgent need.

CONSTRUCTIVE ASPECTS OF LEARNING SCIENCE

Learning, the process of acquiring new knowledge, is active and complex. This process is the result of an active interaction of key cognitive processes, such as perception, imagery, organization, and elaboration. These processes facilitate the construction of conceptual relations.

Science teachers sometimes view students as human video cameras, passively and automatically recording all of the information in a lesson or a textbook. Instead, teachers should view students as active consumers, who are selective and subjective in their perception. The students’ prior knowledge, expectations, and preconceptions determine what information will be selected out for attention. What they attend to determines what they learn. As a result, no two students learn exactly the same thing when they listen to a lesson, observe a demonstration, read a textbook, or do a laboratory activity. Ideally, students will challenge the information they are presented, struggle with it, and try to make sense of it by integrating it with what they already know.

How can teachers help students to learn science concepts meaningfully? The answer is to help students learn concepts relationally. That is, students should learn concepts as organized networks of related information, not as random lists of unrelated facts. Unfortunately, standardized tests of science achievement frequently fail to distinguish between students with relational learning and students with rote learning. If the students are asked to use the concepts in creative problem solving, then the advantage of relational learning over rote learning becomes apparent.

In order to learn a concept meaningfully, students must carry out cognitive processes that construct relations among the elements of information in the concept. Students should then construct relations between the concept and other concepts. Without the construction of relations, students have no foundation and framework on which to build meaningful conceptual networks. The meaningfulness of these networks depends on both the elements of information that comprise the networks and the relations that weld the elements together.

ORGANIZATIONAL AND ELABORATIVE PROCESSES

The most important questions that psychologists and science educators must answer are: (1) What processes should science students perform and what relations should they construct in order to comprehend science concepts? and (2) In what ways can these processes and relations be supported by instruction?

It is known that organizational and elaborative processes play a particularly important role in science learning. Studies done of experts and novices in fields such as physics (e.g., Chi, Feltovich, & Glaser, 1981) and medicine (Feltovich, 1981) have shown that experts not only have more knowledge than novices, but also better organized and elaborated knowledge.

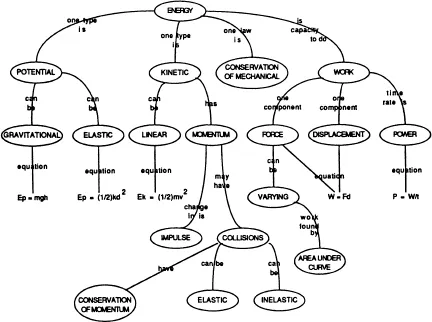

Organizational processes are essential for building conceptual networks. Science teachers can support students’ organizational processes by techniques such as concept mapping. A concept map is an effective way of depicting both the elements of information in a conceptual network and the hierarchical relations among the elements. Relations of other kinds, such as causal and temporal, are also specified in the map. The teacher can construct a concept map and use it to plan a lesson. For example, Fig. 1.1 shows a high school physics teacher's map of the unit “Conservation of Energy and Momentum,” which includes the concepts of work, power, energy, and momentum.

FIG. 1.1. A teacher's concept map. From “Building an Organized Knowledge Base: Concept Mapping and Achievement in Secondary School Physics,” by William J. Pankratius, 1990. From Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 27, p. 328. Copyright 1990 by the National Association for Research in Science Teaching. Reprinted by permission.

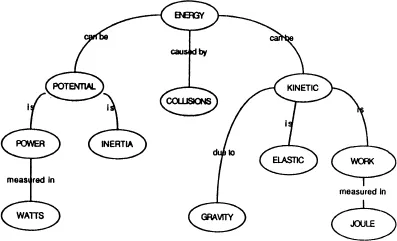

Students should construct their own concepts maps. The teacher can use the students’ maps to diagnose and remediate misconceptions (see Fig. 1.2). As the student learns more and more about the concepts in question, their concept maps will evolve, becoming more sophisticated, and eventually approximating those of the teacher (see Fig. 1.3). By comparing the concept maps that students produce over the course of instruction, the teacher can trace developments in students’ conceptual networks. Concept mapping should be an active, constructive activity: It is unproductive for the teacher simply to present a concept map to students and instruct them to memorize it.

FIG. 1.2. A student's preinstruction concept map. From “Building an Organized Knowledge Base: Concept Mapping and Achievement in Secondary School Physics,” by William J. Pankratius, 1990. From Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 27, p. 329. Copyright 1990 by the National Association for Research in Science Teaching. Reprinted by permission.

FIG. 1.3. A student's postinstruction concept map. From “Building an Organized Knowledge Base: Concept Mapping and Achievement in Secondary School Physics,” by William J. Pankratius, 1990. From Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 27, p. 331. Copyright 1990 by the National Association for Research in Science Teaching. Reprinted by permission.

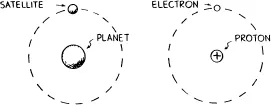

FIG. 1.4. An analog drawn between a gravitational field and an electrical field. From Conceptual physics (p. 496) by Paul G. Hewitt, 1987. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley. Copyright 1987 by Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. Reprinted by permission.

By means of elaborative processes, students connect new elements of information with elements they already know. Helping students to draw an analogy, such as that illustrated in Fig. 1.4, is an effective way of promoting elaborative relations (Glynn, 1989; Glynn, Britton, Semrud-Clikeman, & Muth, 1989). At the same time, teachers should ensure that students understand that analogies are double-edged swords. That is, an analogy can be used to explain correctly and even predict some aspects of a new concept; but at some point every analogy breaks down. At that point, misconceptions can begin. Students must understand this.

THE HUMAN INFORMATION-PROCESSING SYSTEM

Students are selective in their cognitive processing of information because their minds, which can be conceptualized as information-processing systems, are quite limited in the ability to...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- Part I: Frameworks for Learning Science

- Part II: Conceptual Development And Learning Science

- Part III. Methods And Media For Learning Science

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Psychology of Learning Science by Shawn M. Glynn,Bruce K. Britton,Russell H. Yeany in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.