- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding International Art Markets and Management

About this book

This groundbreaking text brings together experts in the field of visual art markets to answer some fundamental questions:

- Is art a good investment?

- Why is the art market dominated by America and Western Europe?

- Where are the key emerging markets and what are the next good buys in art?

Providing readers with an understanding of the challenges facing art market 'makers' (dealers, auctioneers, collectors and artists) and the decision-making process experienced by market 'players' and investors, this exciting text merges the key theories with examples of practice in a highly accessible style.

Written by an international array of experts from the US, the UK and China, this book is essential reading for all those studying or interested in art markets and management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Understanding International Art Markets and Management by Iain Robertson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art & Business. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art & Business1 Introduction

The economics of taste

Iain Robertson

No arts; no letters; no Society; and which is worst of all continual fear and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

(Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, 1651, ch. 13, p. 62)

On 5 May 2004 at 7.25 p.m. New York time, in the space of five minutes Picasso’s ‘Boy with a Pipe’ was hammered down to an anonymous bidder for $93 million, a price which rose to $104 million (£58 million) after Sotheby’s added its colossal $11 million commission. A number of things can be said about this event. The first is that ‘Boy with a Pipe’ is now either the most or, in real terms, the third most expensive work of art ever sold at auction. The second is that the prices paid for art and antiques since the late 1980s are the highest ever. If the extravagant Duke of Saxony had been pitched against the Picasso buyer in a bidding battle of similar magnitude for Raphael’s ‘Sistine Madonna’ (a painting the Duke acquired in 1754) he would have needed 163 times more cash. The third is that the capital returns on the Picasso have earned the vendor the equivalent of 64 per cent interest per annum over 54 years. The fourth is the morally suspect circumstances in which the work was sold, with the wife of its original owner, Mendelssohn- Barholdy, allegedly having sold the painting to a dealer against the wishes laid down by her deceased husband in his will. What does all this tell us about the art market, its past, present and future? Indeed, what is the art market? This book aims to give you the answers.

Art, some argue, stands between us and the bleak life vision encapsulated in Hobbes’s epigraph to this chapter. Public sector curators, the descendants of Shaftesbury’s leisured, landed class of gentlemen philosopher who achieved virtue through taste, are the self-appointed custodians of this ‘treasure’. Yet, how disinterested, how unsullied by Hobbes’s life are these connoisseurs of beauty? A profession by the early nineteenth century, connoisseurship imagined that it might reveal pictorial beauty through forensic analysis. Giovanni Morelli, the founding father, searched for the artist’s signature brush mark in an inconsequential fragment or detail and his method informed the processes by which the likes of Bernard Berenson and Max Friedlaender made their attributions. These pictorial flourishes are not always a cast iron guarantee of authorship, but as Peter Schatborn, who revised Benesch’s list of Rembrandt drawings in the early 1990s, says the stylistic traits are the most important elements in determining authenticity. These people are important because the entire art market edifice rests on their pronouncements. The reduction of aesthetic judgement and valuation to a quasi-science is the reason that we have an art market, but how much of its credibility lies in the suspension of our disbelief? How much of the market is predicated on our desire for order and on our understanding that value today means money?

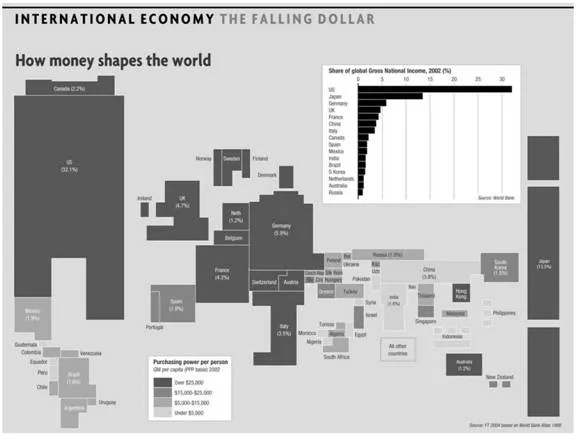

Plate 1.1 Economic world map (Financial Times, 2004 based on World Bank Atlas, 1998)

Art and money might still seem like uncomfortable bedmates, but in this book the relationship is sacrosanct. Art, here, is presented as a luxury commodity,1 an ‘experience good’ that has to be tested or consumed before its true quality is revealed. It is also treated as an ‘information good’, since so much of its value is tied to an idea. The acquisition of art, a tangible ‘consumption good’ with ‘social capital’, is also seen as a positive addiction; the more that it is consumed, the more that it is desired. On the other hand, this book avoids any attempt to correlate monetary value with artistic quality or to express normative views on the quality of art. The great difficulty, however, is that so much of the value of art is tied to the ‘judgements’ of the commercial art establishment, that enjoy a monopoly of taste. The monopolists have access to privileged information that is not made universally available and so the market is drastically distorted in favour of the few. It is the élite nature of this market mechanism that maintains art’s high unit value and encourages the perception that it is the ultimate consumer good.

This book examines art from a number of positions. The dominant one is economic and informed by Hobbes’s vision of a bourgeois capitalist society in which perpetual motion, prompted by fear (the fear of death) leads to endless struggles for power. In this world, man is motivated by ‘appetites’ and ‘aversions’ and stimulated to act by the action of ‘externall objects’. A crucial aspect of Hobbes’s grand design is that ‘appetites’ continually change and are different in different men, and are incessant and of different strengths in different men. A man’s power is relative to others and, ‘The value, or WORTH of a man, is as of all things, his Price; that is to say, so much as would be given for the use of his Power’ (Leviathan, Ch. 10, p. 42). Some men, Hobbes asserts, have unlimited desires, but all men seek to increase their power at the expense of others. The only society that can contain Hobbes’s hungry creatures peacefully, is the Capitalist.

The international art market operates, with finesses, almost entirely on this model of bourgeois society laid out by Hobbes in Leviathan.

In affirmation of Hobbes, Bruno Frey declares that the economic approach to the study of art starts with the preferences or values of individuals whose views are shaped to a great extent by institutions (Frey, Peacock and Rizzo in Towse, 2003). This approach stops just short of saying what is and is not art: ‘As economists we have nothing to say on this subject; let the experts define the arts as they please, and then try to measure them economically’ (Brosio, Peacock and Rizzo in Towse, 2003, p. 17). Art is thus defined by individual actors, determined by exogenous developments and subject to changes in value, correlated to changes in taste, over time (Brosio, Peacock and Rizzo in Towse, 2003). Taste is impossible to ‘capture’ economically, which makes the task of achieving price transparency all the harder. We argue, using Hobbes’s resolutive-compositive method, that because art is determined by institutions with a monopoly of taste, art is only art when it has passed through certain mechanisms. Since money is the accepted medium of exchange for the transference of power, of which taste is one manifestation, art is only art when it has been exchanged for money. Transactions will, by definition, take place within the system. Art has by extension, therefore, latent art potential when it rests in a conduit before a sale, and is not art if it fails to appear in an art market conduit.

There is a growing body of literature dealing with the market for art. Most of it is focused on the role played by the public sector in capturing taste, arguing for or against the necessity of public arts subsidy. Frey, for example, argues sensibly for the need for the public sector to capture certain economic effects, such as public good. The Neo-Classical economist, Grampp, suggests that art should be treated like any other commodity. The Jonas Chuzzlewit school of economics - ‘Do other men, for they would do you’ (Dickens, Martin Chuzzlewit, Ch. 11) - is close to the reality of art market behaviour, but it has many detractors. Some writers believe that the instrumentalrational approach adopted by Neo-Classical economists in assessing the value of art to be fundamentally wrong. Those writers (Becker for example) might propose a sociological-economical network approach. Then there are the art historians, like Reitlinger, Wood and Cumming, who employ art-historical critiques alongside price histories.

The art that this book deals with is confined to the world of paintings, drawings sculptures (and their derivatives in the form of multiples), antiques and antiquities. All this art is purveyed through specialist retailers. The sales outlets are commercial galleries and the art fairs they attend, antique shops, auction houses, ‘dirt’ markets and commodities sold in so-called art warehouses by independent specialist traders, in some department stores and the artist’s studio. Two complications should be immediately evident. The first is the extreme difficulty of tracking even a small percentage of the transactions conducted daily on the international art market and the second is the implied ability of the retailers to determine what is art rather than leave it to the artist, traditional connoisseur or museum curator.

Economic determinism, which is based on the premise that economic growth promotes democratization, ensures re-election and is the key to international power, is, according to Niall Ferguson (2001), close to being conventional wisdom - particularly in the United States. Ferguson goes on to argue, persuasively, that the value of money is sustained by political power and that power in turn is determined by societal demands which are often irrational. Culture is one of those irrational demands. We do not actually need it to survive, but it is certainly a strong want. The absorption, and later export, of their culture by powerful democratic governments helps define our world. Art and antiques are a sub-set of this broadest sense culture, and being commodities are particularly affected by money. The direct association between art and antiques and money elevates our commodity to the highest reaches of the capitalist tree. In short, art and antiques are the most easily translatable of the cultural commodities into the universally understood medium of exchange - money - and are consequently, on one level, the easiest to understand.

The art market is remarkable but not unique in having a substantial degree of ongoing support from the state in the form of grants to public museums and galleries. It is positively and negatively affected by pubic sector inter-ventionism. Other commercial industries in Europe, if not in America, are also periodically subsidized: agriculture, car manufacture, the mining and steel industries to name four, but the arts are criticized because they are unproductive and appeal to a minority of the population. The counter arguments are that the marketplace is unable to capture all of art’s value, and the pleasures and rewards of art should be accessible to all. The art that is supported by the public sector is of a particular type, and many practitioners and intermediaries argue that the vast range of production over the last hundred years or so is ignored in favour of a thin commercial cutting-edge. This has happened because public sector accession policies are opaque and undemocratic and fed by favoured networks. The fact that today’s political élite is not necessarily its cultural élite might appear to challenge this assumption, but the arts establishment (an agenda-driven interest group) on both sides of the Atlantic is adept at presenting arguments to satisfy the paymaster. These arguments cover a range of effects that fall within the public interest. They permit a former director of the Arts Council, Luke Rittner, to say after the sale of Picasso’s ‘Boy with a Pipe’ that ‘It would be a tragedy if this wonderful picture were to be kept from public view’ (Wapshott, 2004).

One is tempted to say the public couldn’t care less, but then most governments squeal on the twin pikes of access and excellence. I am inclined to agree with Robert Hughes when he says that art, like war, is a minority taste.

The public sector performs a dual function. It validates the art made today and authenticates the art of the past. It prevents, through selection and in conjunction with commercial art dealers and brokers, the market from being over-loaded, a situation that would lead to a fall in art’s unit value. But it hoards and fails to release works back onto the market. There are, for example, only three Rembrandts still in private hands (Alberge, 2003). The prevention of the movement of this portable asset from one set of collectors to another is justified by a series of public good and national pride arguments. There is also an art historical argument that maintains that public gallery collections add to the understanding of an artist or movement. There are equally strong counter arguments. Many works of art, especially religious artefacts, are best seen in the churches, temples and grottoes from which they were appropriated. Special exhibitions are just as capable of bringing great works together as are permanent museum displays. A work of art, which is made for trade, loses much of its meaning when it is wrenched from the market and institutionalized. The real reasons for the restrictions placed on the flow of art owe more to political expediency, intellectual posturing and precedent than convincing argument.

The UK political arts establishment appears to group de-accessioning beside free admittance to public collections. I would agree that once a work ‘rests’ in a public institution the work is public property and admittance should be free. If, on the other hand, a museum decides to sell one of its assets it should be allowed to benefit financially from the transaction. The two views can co-exist quite happily. The preciousness with which we treat our art in times of peace is matched only by our total disregard for it in times of war. Iraq is simply the latest example.

The use of art for utilitarian purposes has formed an important part of public policy in the UK since the Myerscough report in 1987. Since then there have been other reports written on the economic benefit of the arts to the general economy. UNESCO produced a report on the cultural flows of selected cultural goods from 1980 to 1998 and the Department of Culture Media and Sport produced its second examination into the monetary value of the cultural industries in 2001. These enquiries and their findings are of little help to the trade. They are aimed at persuading Treasuries to continue to fund the public sector. It is fair to say that the market does not actually need the public sector but it would rather not have to do without it.

The efficient markets hypothesis (EMH) has governed the way we view financial markets since 1970 (Fama, 1972). An efficient market is one in which security prices always fully reflect the available information. Today, the idea that financial markets (arguably the world’s most perfect) can be efficient has been strenuously challenged by behavioural finance and the concepts of limited arbitrage and investor sentiment. Behavioural finance maintains that the biased, the stupid and the confused operate in competitive markets in which at least some arbitrageurs are fully rational. These factors, combined with a haphazard knowledge on how real-world investors form their beliefs and valuations, lead to very low levels of price prediction (Shleifer, 1999). If these ‘realities’ are true of the financial markets how much truer are they of the art market where Baumol (1986) cited in Towse (2003, p. 58) has observed:

- On financial markets, a high number of homogeneous, substitutable stocks and shares are bought and sold, whereas the degree of substitutability is almost nil in the case of artistic products, given the fact that they are unique.

- The owner of a work of art enjoys a monopoly, whereas a stock is owned by a number of investors, who, theoretically, act independently of one another.

- The transactions relative to a particular stock or share take place in time almost continuously, whereas transactions concerning a particular work of art may be several decades apart.

- The fundamental value of a financial asset is known: it is the present value of the expected flow of income; on the contrary, the work of art has no long-term equilibrium price.

- The costs of holding and transacting are much higher for works of art than for stocks and shares: insurance costs are high, there are charges borne by the seller and the buyer at auction, although on the other hand the taxes incurred by these goods may be more advantageous.

- Finally, art, unlike stocks and shares, does not provide positive monetary dividends: its ownership may imply negative dividends in the form of insurance and restoration costs; it does, however, afford psychological dividends in the form of cultural consumption and services.

Part I of this book takes a topographical view of the art market, mapping its structure. It sees it within a global context and aligns it to other markets and takes into account human behaviour. In Chapters 2 and 3 I look first at the internal forces that drive today’s art market locomotive and then at how these same forces have shaped past art markets. I use financial terms to give sense to the art market and break it down into category, sector, type and commodity. The art market is not global like the food and drinks market, but it is international and operates from select centres around the world. I show that without the wealth developed by bankers and accrued from global trade, the art market would have remained undeveloped. In Chapter 4, Eric Moody questions whether these forces are manageable, and whether the market is, as Adam Smith has it, guided by an invisible hand, or indeed significantly biased in favour of a self-appointed élite. Derrick Chong examines, in Chapter 5, the three prominent relationships in the contemporary art market; dealer-artist, dealer-collector and collector-artist and looks at the art market from the Classical economic perspective of production- distribution-consumption. In Chapter 6, Renée Pfister shows how the price of a picture depends on where it is sold. The cost of importing Rothko’s painting, ‘No. 9’, to the EU would, she explains, add $458,722 to its $8.95 million sales price excluding national sales tax. The same work would attract $686,519 ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: The Economics of Taste

- Part I: The structure and mechanisms that fuel the art market

- Part II: The behaviour and performance of the main markets for art

- Part III: Conclusion