eBook - ePub

The Initial Period of War on the Eastern Front, 22 June - August 1941

Proceedings Fo the Fourth Art of War Symposium, Garmisch, October, 1987

- 528 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Initial Period of War on the Eastern Front, 22 June - August 1941

Proceedings Fo the Fourth Art of War Symposium, Garmisch, October, 1987

About this book

Beginning with Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, this volume draws upon eye-witness German accounts supplemented with German archival and detailed Soviet materials. Formerly classified Soviet archival materials has been incorporated.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Initial Period of War on the Eastern Front, 22 June - August 1941 by David M. Glantz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Prelude to Barbarossa

The Red Army in 1941

DAVID M. GLANTZ

Over the course of three symposia, we have investigated how the Red Army eventually solved its basic offensive problems during the Russo-German war, problems which became readily apparent during the first two years. Central among those many problems was that of developing a capability for achieving operational success in offensive operations. That meant, in essence, Soviet creation of a mobile armored and mechanized force, new combat techniques to govern the operations of that force, and command and control systems which would enable that force to develop tactical success into operational and, hence, strategic success. This process progressed from its first tentative steps in late 1942 into a major Soviet capability in 1945. Now we shall look at the problems the Soviets encountered when they attempted to develop the capability for conducting deep operational maneuver, problems which, as we shall see, were woefully apparent to all parties in 1941.

We shall investigate in detail the problems of the Red Army in the initial period of the Russo-German War or, as the Soviets refer to it, the Great Patriotic War. We shall do so by surveying the expectations of the Soviets on the eve of war: in particular, how the Red Army was to function in theory. We shall examine its strategic plans, its operational and tactical techniques, and its organizational structure. We shall then view the Red Army as it attempted to practice war during the first critical months after the Germans launched Operation Barbarossa. What interests us most are the answers to three questions. First, what was the gap between theory, in terms of Soviet expectations, and practice, the reality of combat? Second, what did the Soviets do to close that gap? And third, what fundamental lessons have the Soviets derived from their close examination of the initial period of war, a topic which itself has become a major area of contemporary concern to the Soviets, both from the standpoint of German offensive operations and from the standpoint of Soviet defensive measures? Today, the Soviets articulate that issue by asking the question: in the initial period of war, what must a nation do to achieve quick victory or, conversely, avoid rapid defeat? The events of June and July 1941 remain a critical element of military experience which the Soviets continue to exploit when attempting to answer that momentous question.

The Red Army of the 1920s was essentially a foot-and-hoof army: an infantry and cavalry force with very limited capability for developing tactical success into operational or certainly strategic success. The Soviets identified this problem very early. In the 1920s, they pondered a whole series of problems and major questions, many of which the Western powers pondered too. The most important questions were: “How does one escape the crushing weight of firepower which produced the linear warfare experienced in the First World War? And how does one restore maneuver to the modern battlefield?” To answer these questions, the Soviets drew upon some Western experiences in the First World War, for example German operations in 1918, and they drew upon their own experiences in the Russian Civil War, a war of maneuver conducted across vast expanses. The Soviets, in essence, focused their attention on how to restore mobility and maneuver to warfare.

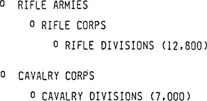

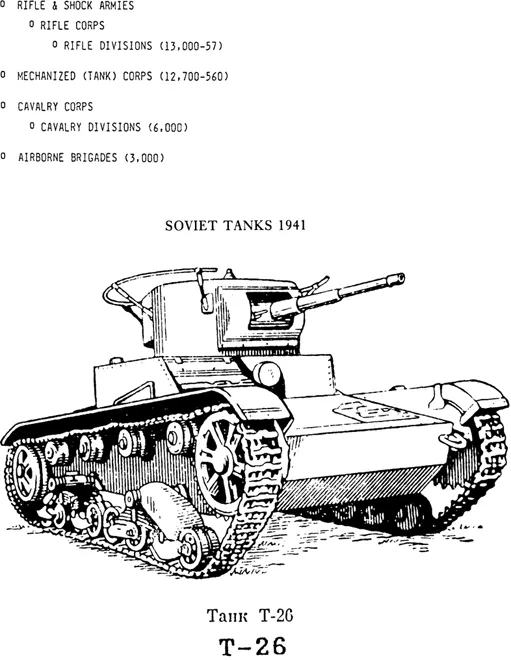

The Soviet force structure in the 1920s was very large, but it lacked the ability to conduct deep sustained maneuver (see Figure 1). Large rifle armies were subdivided into rifle corps, which in turn were subdivided into rifle divisions. The traditional mobile arm consisted of cavalry corps, which were subdivided into cavalry divisions. The experiences of the First World War, and to some extent those of the Civil War, evidenced the inability of cavalry to function effectively given the crushing weight of firepower characterizing twentieth-century warfare.

FIGURE 1 RED ARMY FORCE STRUCTURE IN THE 1920s

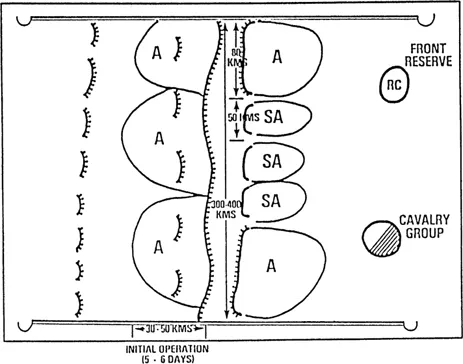

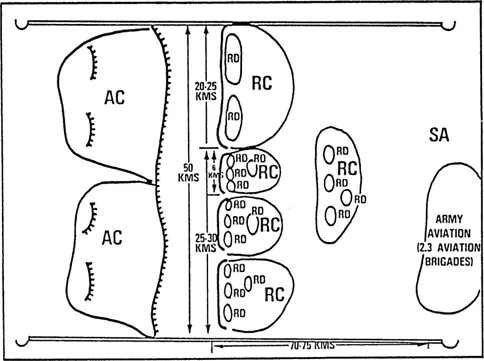

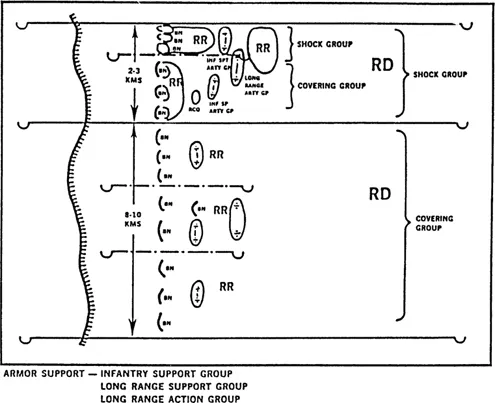

The Soviets employed this foot-and-hoof force structure in a rather conventional way. In 1930 Soviet forces at front (army group) level operated in the following general pattern (see Figure 2). Heavy shock armies were to conduct the penetration operation in order to smash through the enemy’s tactical defenses, and thereafter, cavalry groups consisting of single cavalry corps or multiple cavalry corps were designated to exploit the tactical success of rifle forces into the operational depths. It was not an adequate system by any means. At the army level the same general pattern existed. Soviet Army commanders relied upon heavy infantry formations and lacked mobile units possessing resilience and hence, sustainability (see Figure 3). Rifle corps blasted through enemy tactical defenses and their success was exploited by rifle corps lined up behind, in virtual second echelon. At the division level, the same pattern held true. The Soviets relied on infantry shock groups, as the Soviets called them, to achieve the tactical penetration and covering groups to hold along secondary axes (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 2 FRONT OPERATIONAL FORMATION (OFFENSE), 1930

FIGURE 3 ARMY OPERATIONAL FORMATION (OFFENSE), 1930

FIGURE 4 RIFLE DIVISION COMBAT FORMATION (OFFENSE), 1930

In the late 1920s the Soviets began to perceive the solution to their problem. The solution seemed to rest in the creation of motor-mechanized armored forces. It is, however, one thing to theorize about change and altogether another to actually effect change in practice. By 1929 the Soviets had incorporated into their Field Service Regulations the promise of conducting deep battle in the future, the Russian term glubokii boi. Deep battle meant battle conducted by mechanized and armored units designed both to support infantry and to penetrate tactical defenses, thus it was a tactical concept. Shortly after, the Soviets began creating mechanized and armored forces; first tank battalions, then mechanized and tank brigades, and finally even larger forces as the Soviet Union progressed in the 1930s. Figure 4 shows some of the earliest Soviet concepts for the use of those infantry support tanks. Various tank groupings were formed to support the initial assault and to assist advancing troops as they penetrated into the tactical depths. The 1929 Field Service Regulation (USTAV) gave direction to Soviet efforts and, of course, it was the Five Year Plans, beginning in the late 1920s, that provided the wherewithal, the weaponry necessary to implement this concept. It was a very short step indeed from producing tractors to producing tanks and the Soviets made that step quickly.

By the mid-1930s the Soviets had fully developed and implemented the concept of deep battle (glubokii boi). They had also constructed a force structure that could actually translate those theories into practice. Figure 5 shows the force structure that had emerged by 1936. The structure included the traditional rifle and shock armies, which were in turn subdivided into rifle corps and divisions. The significant point here was the fact that armor forces were included in each level of command. Within the lower-level rifle forces this armor was designed essentially to provide infantry support. The numbers shown are personnel and armor strengths according to the TOE or establishment of each force. Incidentally, shock armies were nothing more than heavy rifle armies designated with the task of conducting the main attack.

FIGURE 5 RED ARMY FORCE STRUCTURE IN THE 1930s

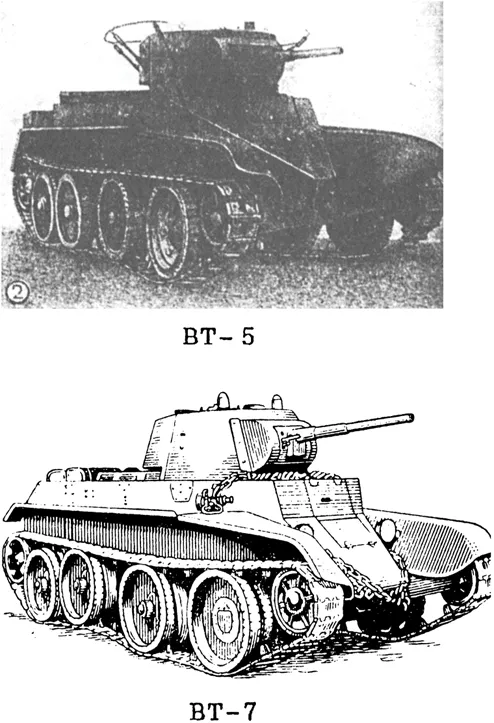

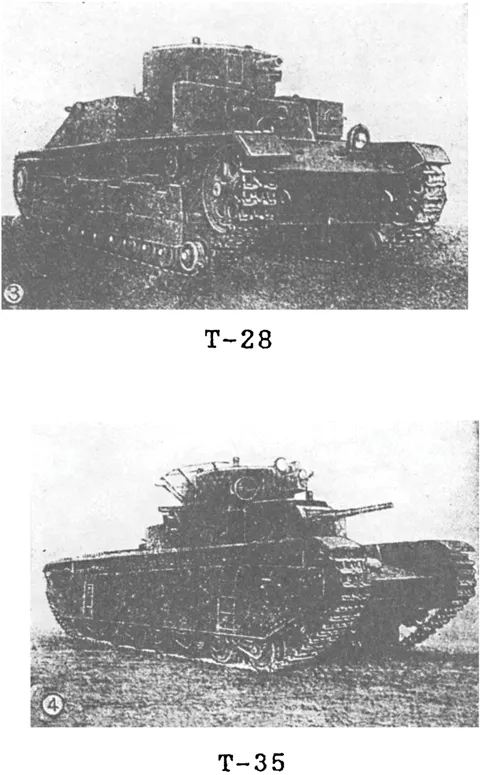

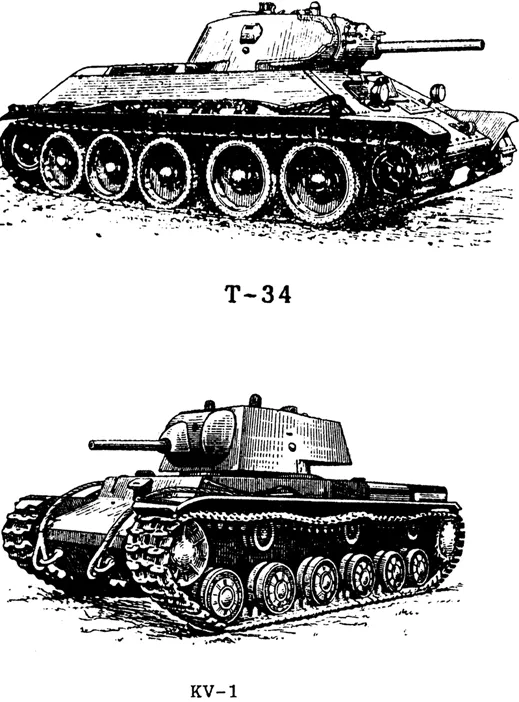

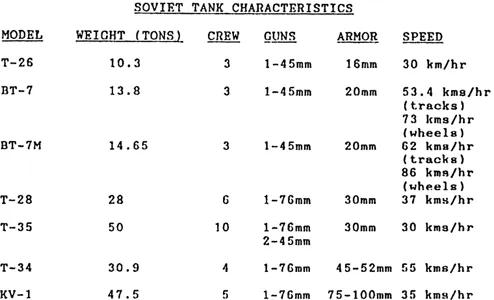

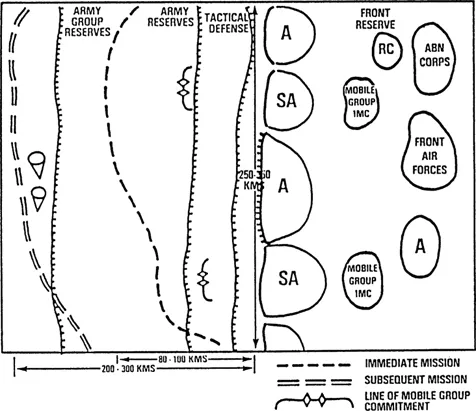

The most important development, however, occurred in the realm of mechanized forces. In 1930 the Soviets created an experimental mechanized (tank) brigade and by 1932 had four of these brigades. By 1936 they had increased the size of these forces to corps and by then they possessed four mechanized corps and a host of mechanized brigades, tank regiments and tank battalions. In other words, they had created armored and mechanized forces that would function at every level of command, to provide both infantry support and a maneuver capability to the Red Army. The mechanized corps of 1936, which we will look at more closely in a moment, had 560 tanks and a personnel strength of roughly a division equivalent. The Soviets still maintained cavalry corps and cavalry divisions, but added to them heavy armor contingents to fight side by side with the horse units. There was a vertical dimension to these maneuver forces as well. The Soviets created airborne brigades in the 1930s and slowly expanded the number and the size of these forces by 1941. The concept from the very start was to foster close cooperation between the ground mobile arm and the vertical dimension, the airborne arm. The new Soviet tank corps (the mechanized corps of 1936 was renamed tank in 1938) consisted of two tank brigades, a rifle machine-gun brigade, and various support units totalling roughly a division’s personnel strength and 560 medium and light tanks (see Figure 6). In addition, the Soviets had light tank brigades and heavy tank brigades, which were principally used for support of rifle units.

FIGURE 6 TANK FORCES, 1938

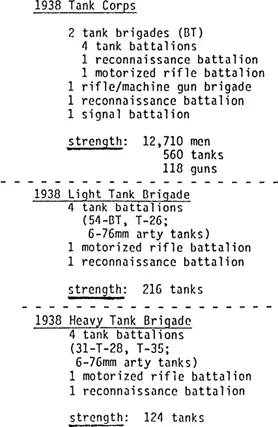

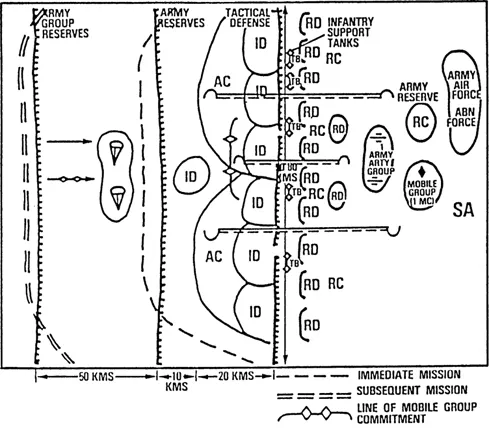

The 1936 Field Service Regulation set out how this new mechanized force was supposed to operate. This is the scheme the Soviets projected at front level (see Figure 7). Shock armies, which were heavy combined arms armies, were designated to conduct the penetration operation to achieve the tactical breakthrough. Thereafter a mobile group (podvizhnaya gruppa )would exploit through the enemy tactical defenses into the operational depths. Figure 7 shows the lines denoting depth of mission (intermediate mission and subsequent mission). It also shows the airborne corps, in existence by 1941, created to cooperate with ground mobile groups in the depths of the enemy’s defenses. Normally a front would contain one or two mechanized corps to function as its mobile group.

FIGURE 7 FRONT OPERATIONAL FORMATION, 1936–41

At the army level there were also mechanized forces integrated throughout by virtue of the 1936 Regulation. This is a shock army configurated to conduct offensive operations (see Figure 8). Tank brigades provided infantry support and a mobile group in the form of a mechanized corps conducted the exploitation operation. Again, an airborne force operated at shallower depths to cooperate with the mobile group. The basic concept shown by this simple diagram, in theory and in practice, would not change for 50 years. The only problem for the Soviets involved converting complex theory into effective practice.

FIGURE 8 SHOCK ARMY OPERATIONAL FORMATION, 1936–41

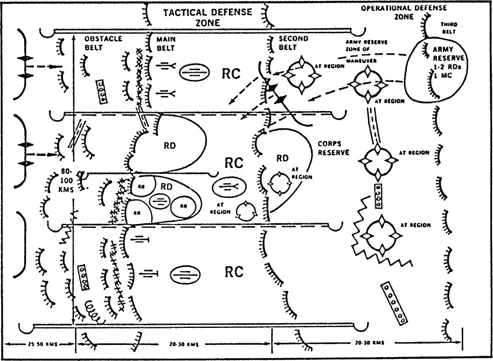

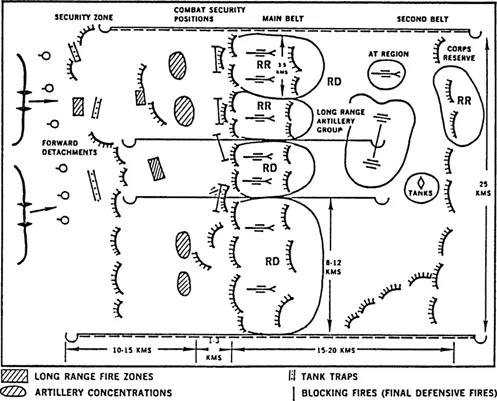

Now just a word about Soviet defensive concepts, since the Soviets were most concerned about defense just before, and especially after, June 1941. According to the 1936 Regulation a Soviet army was supposed to defend in a single echelon of rifle corps, while the corps themselves organized in multiple echelons (See Figure 9). By this time the Soviets had developed the concept of the antitank region as the principal barrier to enemy armored attack. Antitank regions were supposed to be laced throughout the depths of the rifle corps’ defense. The Soviets also planned to use their mechanized corps on the defensive, as a counterattack force to strike against enemy penetrations into the army defensive sector. At corps level the same general pattern pertained, with Soviet use of deeply echeloned defenses and increasingly strong antitank defenses. At least in theory, antitank defense involved the integration of antitank guns down to regimental level and the integration of tanks and antitank regions into the tactical defense of a corps (see Figure 10).

FIGURE 9 ARMY OPERATIONAL FORMATION (DEFENSE), 1936–41

Figure 10 CORPS COMBAT FORMATION (DEFENSE), 1936–41

The Soviets experienced a considerable number of problems in the late 1930s. The purges that literally lopped the head off the Red Army by liquidating half of the officer corps certainly had an adverse impact on Soviet combat performance after 1937 and 1938. But Soviet problems went well beyond the purges. There were some very real experiences that caused the Soviets to question the utility of having a large mechanized force. In Spain for example, the Soviets sent a large armored contingent to support the Loyalist side in the Spanish Civil War. A considerable number of prominent Soviet military figures participated in that experiment. The Soviets generally concluded, as a result of combat in Spain, that armored forces were indeed fragile on the battlefield unless they were fully integrated into a well articulated combined arms force. Tanks proved very vulnerable to artillery fire, and when their supporting infantry was stripped away they were very vulnerable to destruction by enemy infantry as well. When they returned from Spain, many Soviet military leaders recommended the creation of smaller armored units of more balanced combined armed nature.

The Soviets also had rather poor experience using armor in the Finnish War of 1939–40. The one mechanized corps they used accomplished virtually nothing and ended up providing just infantry support. Also in 1939, when Soviet forces rolled into eastern Poland two tank corps took part in the operation. Marshal Eremenko, who was associated with one of those tank corps, commented that the Soviet cavalry corps performed far better than the tank corps, since the tank corps moved at a snail’s pace and were constantly hindered by mechanical and logistical problems.

In fact, the entire Red Army’s logistical state in 1939, in terms of maintenance, and fuel and ammunition supply was poor. Support was insufficient to sustain those large mobile groups as well as the Red Army in combat. Consequently, in late 1939 the Soviets abolished their tank corps, and in their place created a number of smaller entities, one of which was the 1939 motorized rifle division (see Figure 11). This was supposed to be a more balanced combined arms force, and it had a small tank complement of 37 tanks. Shordy after, the Soviets created a second type of mobile division, the motorized division, which consisted of two motorized rifle regiments and a tank regiment with a total strength of 275 tanks. These divisions were supposed to replace the larger and more cumbersome tank corps that had performed so badly in the preceding months. The Soviets maintained in their force structure a variety of tank brigades (see Figure 12). The 1940 light and heavy tank brigades were tailored to provide basic infantry support and were fairly heavy with 258 and 156 tanks respectively. Most of these tanks were older heavy, medium, and lig...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- 1. Introduction: Prelude to Barbarossa

- 2. The Border Battles on the Siauliai Axis 22–26 June 1941

- 3. The Border Battles on the Vilnius Axis: 22–26 June 1941

- 4. The Border Battles on the Bialystok–Minsk Axis: 22–28 June 1941

- 5. The Border Battles on the Lutsk-Rovno Axis: 22 June–1 July 1941

- 6. The Smolensk Operation: 7 July–7 August 1941

- 7. Conclusions

- Index