![]()

Unit 1

1. Demonstrate an understanding of reactance, resonance, transformers and transfer and the practical application of these components and circuits

2. Demonstrate an understanding of semi-conductor devices, displays and transducers and the practical applications of these components.

![]()

26

Sine wave driven circuits

Capacitors and inductors in direct current (d.c.) circuits cause transient current effects only when the applied voltage changes. In an alternating current (a.c.) circuit this is a continuous process. Capacitors in such a circuit are therefore continually charging and discharging, and inductors are continually generating a changing back-electromotive force (emf). Circuits containing resistors, capacitors and inductors are described as complex circuits and an alternating voltage will exist across each component proportional to the magnitude of current flowing through it so that a form of Ohm’s law still applies.

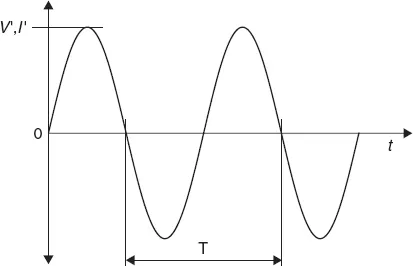

In the explanation that follows, the symbols

V′ and

I′ are used to mean peak a.c. values (

Figure 26.1) of alternating signals. Root mean square (r.m.s.) values are represented by

Vrms and

Irms; that is,

Irms =

I′/. The symbols

v and

i represent instantaneous values of a.c. signals and

V and

I will have their usual meaning of d.c. values. So, we may write

v = V′ sin (2

πft).

Figure 26.1 The peak value and period of a sine wave of voltage or current

For a resistor in an a.c. circuit,

V′ =R × I′ and the value of resistance found from the variant form of this equation,

R =

, is the same as the d.c. value,

V/I. In a capacitor or an inductor, the ratio

V′/I′ is called

reactance, with the symbol

X. Because this is a ratio of volts to amperes, the same units Ω (ohms) are used as used to express d.c. resistance, but it must be remembered this is a frequency-dependent reactance and not a resistance.

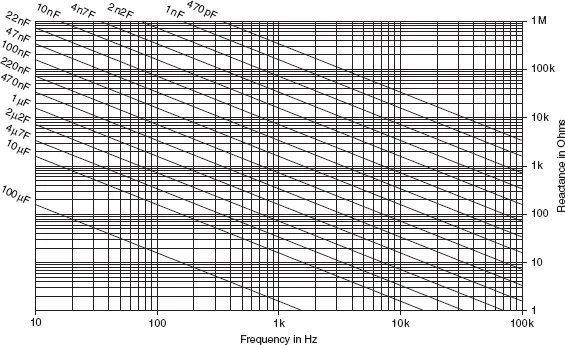

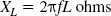

A capacitor may, for example, have a reactance of only 1 KΩ at a given frequency, but a d.c. resistance that is unmeasurably high. An inductor may have a d.c. resistance of 10 ohms, but a reactance of 5 KΩ or more. The reactance of a capacitor or an inductor is not a constant quantity, but depends on the frequency of the applied signal. A capacitor, for example, has a very high reactance to low-frequency signals and a very low reactance to high-frequency signals, as indicated in Figure 26.2.

Figure 26.2 Chart of capacitive reactance at audio frequencies

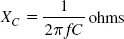

The reactance of a capacitor V′/I′ can be calculated from the equation:

where f is the frequency of the signal in Hz and C is the capacitance in farads. Figures 26.2 and 26.3 show the values of capacitive reactance for a range of different capacitors calculated for a range of frequencies. These charts are intended as a guide so that you can quickly estimate a reactance value without the need to make the calculations.

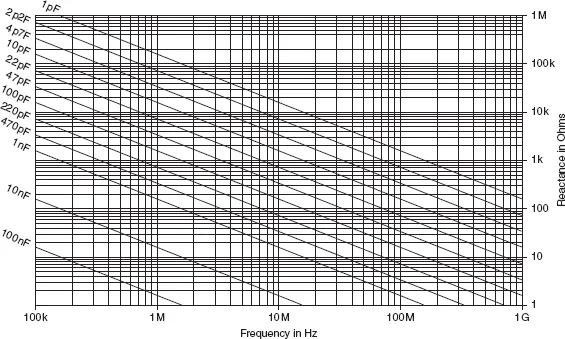

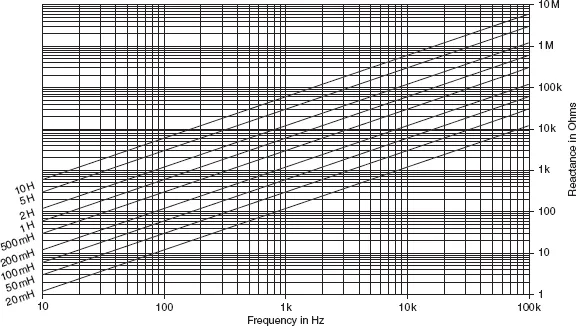

The reactance of an inductor varies in the opposite way, being low for low-frequency signals and high for high-frequency signals. Its value can be calculated from the equation:

where f is the frequency in Hz and L is the inductance in henries. Figures 26.4 and 26.5 show the values of inductive reactance which are found at various frequencies.

Figure 26.3 Chart of capacitive reactance at radio frequencies

Figure 26.4 Inductive reactance at audio frequencies

Figure 26.5 Inductive reactance at radio frequencies

Note: inductors are now less common in circuits other than power supply and radio (transmission and reception) applications. The increasing use of integrated circuits (ICs) and digital circuitry has made the use of inductors unnecessary in a very wide range of modern applications.

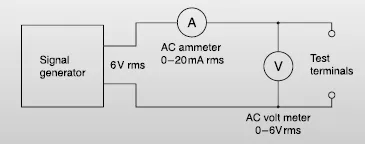

Connect the circuit shown in Figure 26.6. If meters of different ranges have to be used, changes in the values of capacitor and inductor will also be necessary. The signal generator must be capable of supplying enough current to deflect the current meter which is being used.

Figure 26.6 Circuit for practical

Connect a 4.7 μF capacitor between the terminals, and set the signal generator to a frequency of 100 Hz. Adjust the output so that readings of a.c. voltage and current can be made. Find the value of V′/I′’ at 100 Hz.

Repeat the measurements at 500 Hz and at 1000 Hz. Tabulate values of XC = V′/I′ and of frequency f.

Now remove the capacitor and substitute a 0.5 H inductor. Find the reactance at 100 Hz and 1000 Hz as before, and tabulate values of XL = V′/I′ and of frequency f.

Next, either remove the core from the inductor or increase the size of the gap in the core (if this is possible), and repeat the measurements. How has the reactance value been affected by the change?

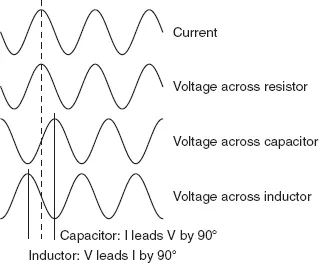

There is another important difference between a resistance and a capacitive or inductive reactance and this can be demonstrated as follows. With the aid of a double-beam oscilloscope, the a.c. waveform of the current flowing through a resistor and the voltage developed across it can be displayed together (Figure 26.7). This shows that the two waves coincide, with the peak current coinciding with the peak voltage, etc. If this experiment is repeated with a capacitor or an inductor in place of the resistor, you will see from the figure that the waves of current and voltage do not coincide, but are a quarter-cycle (90˚) out of step.

Figure 26.7 Phase shift caused by a reactance

Comparing the positions of the peaks of voltage and of current, you can see that:

• For a capacitor, the current wave leads (or precedes) the voltage wave by a quarter-cycle.

• For an inductor, the voltage wave leads the current wave also by a quarter-cycle.

An alternative way of expressing this is that, for a capacitor, the voltage wave lags (or arrives after) the current wave by a quarter-cycle, and for an inductor, the current wave lags the voltage wave by a quarter-cycle.

The amount by which the waves are out of step is usually defined by the phase angle. The current and voltage waves are 90° out of phase in a reactive component such as a capacitor or an inductor.

A useful way to remember the phase relationship between the current and voltage is the word C-I-V-I-L, meaning C–I leads V; V leads I–L. The letters C and L are used to denote capacitance and inductance, respectively.

If we take a few measurements on circuits containing reactive components we can see that the normal circuit laws used for d.c. circuits cannot be applied directly to a.c. circuits.

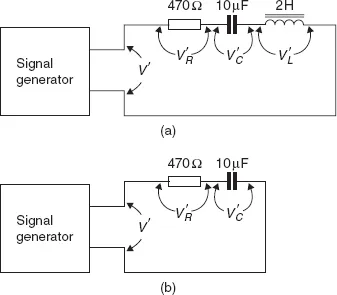

Consider, for example, a series circuit containing a 10 μF capacitor C, a 2 H inductor L and a 470 ohm resistor R, as in Figure 26.8(a). With 10 V a.c. voltage, V′ at 50 Hz applied to the circuit, the a.c. voltages across each component can be measured and added together: V′c + V′L + V′R. You will find that these measured voltages do not add up to the voltage V′ across the whole circuit.

Figure 26.8 Series circuits: (a) RLC, and (b) RC circuit for practical example

Connect the circuit shown in Figure 26.8(b). Use either a high-resistance a.c. voltmeter or an oscilloscope to measure the voltage V′R across the resistor and the voltage V′C across the capacitor. Now measure the total voltage V′ and compare it with V′R + V′C.

The reason why the component voltages in a complex circuit do not add up to the circuit voltage when a.c. flows through it is due to the phase angle between voltage and current in the reactive component(s). At the peak of the current wave, for example, the voltage wave across the resistor will also be at its peak, but the voltage wave across any reactive component will be at its zero value. Measurements of voltage cannot, however, indicate phase angle. They can only give the r.m.s. or peak values for each component, and the fact that these values do not occ...