- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Animals in Celtic Life and Myth

About this book

Animals played a crucial role in many aspects of Celtic life: in the economy, hunting, warfare, art, literature and religion. Such was their importance to this society, that an intimate relationship between humans and animals developed, in which the Celts believed many animals to have divine powers. In Animals in Celtic Life and Myth, Miranda Green draws on evidence from early Celtic documents, archaeology and iconography to consider the manner in which animals formed the basis of elaborate rituals and beliefs. She reveals that animals were endowed with an extremely high status, considered by the Celts as worthy of respect and admiration.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Animals in Celtic Life and Myth by Miranda Green in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE NATURAL WORLD OF THE CELTS

Modern urban dwellers are cushioned, to an extent, from the rhythm of the seasons, from the immediate effects of good or poor harvests and of the health and fertility of flocks and herds. But in any pre-industrial and essentially rural society, the association of communities with the natural environment and their dependence on it are both close and direct. The world of the Celts was no exception. The single farm or small nucleated settlement was the home of many Celtic peoples, and even the large communal centres, like Danebury in Hampshire or Bibracte in Burgundy, were not so very far removed from the surrounding countryside.

For the Celts, the effect of this constant interaction with nature manifested itself in many ways. The pre-Roman Celtic artist, who expressed himself mainly, though not exclusively, through the medium of metalwork, chose as his themes the plants and animals by which he was surrounded in his daily life.Anthropomorphic representation was of less interest to the Celtic metalworker. Sometimes the foliate and zoomorphic designs depicted were fantastic, unreal and full of imagination, but these fantasies do not conceal the fact that the artist had a deep understanding of his subjects. The bronzesmith and blacksmith appreciated, indeed revered, the beauty and the elegance of animals and the sinuous curves of foliage, and, by exaggerating some of their features, enhanced and promoted their aesthetic qualities.

The natural world of the Celts is nowhere manifested more clearly than in the realms of religion, ritual and myth. For the Celts, the supernatural forces perceived in all natural phenomena could not be ignored but had to be appeased, propitiated and cajoled. In Celtic religion, it was the miraculous power of nature which underpinned all beliefs and religious practices. Thus, some of the most important divinities were those of the sun, thunder, fertility and water. These were the pan-Celtic deities: the celestial gods, the mother-goddesses and the cults of water and of trees transcended tribal boundaries and were venerated in some form throughout Celtic Europe. Every tree, mountain, rock and spring possessed its own spirit or numen.

The divine sun was represented by the symbol of the spoked wheel as early as the later Bronze Age: in pre-Roman and Romano-Celtic Europe, the solar force was manifest as an anthropomorphic divinity who none the less retained his original wheel motif to represent the moving sun in the sky. The spirit of the sun was capable of creating and destroying life: it could fertilize or shrivel the crop in the ground; it was a promoter of healing and regeneration, and was even able to light the dark places of the underworld. Water was acknowledged as a powerful force, again from early in European prehistory. For the Celts, the numina of rivers, marshes, lakes and springs were potent supernatural beings who, like the sun, could both foster and destroy living things. Water was perceived as mysterious:it falls from the sky and fertilizes the land; springs well up from deep underground and are sometimes hot, with therapeutic mineral properties; rivers move, apparently with independent life; bogs are capricious, seemingly innocuous but treacherous. All these aquatic forces were venerated, propitiated and given offerings. In the Romano-Celtic period huge, wealthy cult establishments grew up around curative springs presided over by such divinities as Sulis at Bath in Britain and Sequana near Dijon in Gaul.

Single trees, woods and groves were sacred. Before the historical Celtic period, open-air sanctuaries, like the sixth-century BC Goloring enclosure in Germany, had as their cult focus a sacred post or living tree. This tradition was maintained by communities all over Celtic Europe, from the fourth century BC until (and indeed beyond) the end of official paganism in the fourth century AD. Thus, at the third-century BC ritual enclosure of Libenice in Czechoslovakia, there were sacred wooden pillars or trees that had been adorned with great bronze torcs or neckrings as if they were cult statues.At the opposite corner of the Celtic world, the late Iron Age shrine of Hayling Island in Hampshire was built around a central pit holding a post or stone.The Romano-Celtic sanctuary of the Mother-Goddesses at Pesch in Germany had a great tree as a cult focus. At Bliesbruck in the Moselle, numerous sacred pits were filled with votive offerings which included the bodies of animals and tree-trunks. Romano-Celtic iconography emphasizes the importance of trees in cult expression: altars to the Rhineland Mothers and the sky-god are decorated with tree symbols. The groups of public monuments known as ‘Jupiter-Giant Columns’ were composed, in part, of tall pillars carved to represent trees. The ancient Roman writer Pliny refers to the sacred oak of the Druids. Epigraphy alludes to Pyrenean deities called Fagus (Beech-Tree) and ‘the God Six-Trees’. The sanctity of trees seems to have been based on their height, with their great branches appearing to touch the heavens; their longevity; and the penetration of their roots deep underground. They thus formed a link between the sky, earth and underworld. In addition, trees reflected the cycle of the seasons, with the ‘death’ of the deciduous tree in winter and its miraculous ‘rebirth’ with the burgeoning of new leaf-growth in the spring. The Tree of Life allegory was perhaps enhanced by the fact that animals use trees both for shelter and for food.

The sanctity of natural phenomena and of all elements of the landscape led inevitably to the veneration of the animals dwelling within that landscape. Accordingly, wild and domesticated species were the subject of elaborate rituals and the centre of profound belief-systems. The Celts depended on domestic beasts for their livelihood, on wild creatures for hunting and on horses for warfare. This intimate relationship between human and animal in so-called secular life stimulated the concept of beasts as sacred and numinous, whether in possession of divine status in their own right or simply acting as mediators between the gods and humankind.Animals were sacrificed in rituals which sometimes involved eating all or part of the carcase but, on other occasions, the animal was very deliberately left unconsumed, as an unsullied gift to the supernatural powers who had provided humans with these beasts and who demanded offerings which meant a very real loss to the community. The sacrifice of animals must have represented more than simple offerings of valuable commodities.Examination of the evidence for religion in the Romano-Celtic period, when images and epigraphy present us with clues as to how the divine world was perceived, shows us a whole range of deities whose names, cults andidentities were intimately associated with, and indeed dependent upon, the animals depicted with them. This intimacy reached its peak in the perception of gods in human form taking on the features of the beasts themselves – hooves, horns and antlers. Moreover, sacred animals could be envisaged and depicted not only as the normal creatures recognizable within the everyday world but also as fantastic beasts whose multiple horns or composite form remind us, indeed, of the weird and wonderful creatures of the Book of Revelation: ‘and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns . . .’ (Revelation 12.3).

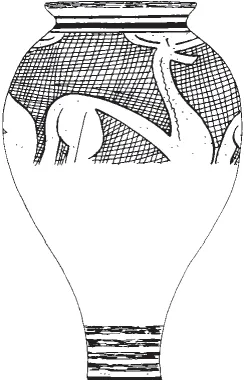

Figure 1.1 Iron Age pot with deer motif, Roanne, Loire, France. Paul Jenkins, after Meniel.

A major theme which is explored in this book is the close link between the sacred and the mundane. It is quite impossible to separate the profane and spirit worlds, or the ritual from the secular aspects of society. Such a division is spurious and should not be attempted. It is certain that ritual pervaded most, if not all, aspects of life and was confined neither to specific ceremonies nor to formalized religious structures. The association between humans and animals expresses very clearly the conflation of cult and the everyday: the killing of animals, whether for food or for sport, had a ritual aspect; warfare was closely bound up with ceremony and religion; for the Celtic artist symbolism, sometimes overt religious symbolism, was central to his repertoire. The vernacular sources, too, show us a world where heroes straddle the realms of the mundane and the supernatural, where animals can speak to people and where divine beings can change at will between human and animal forms. These early Celtic documents open a door on a world of shifting realities and ambiguities, where animals interact closely with both humankind and the gods. To the Celts, animals were special and central to all aspects of their world.

2

FOOD AND FARMING: ANIMALS IN THE CELTIC ECONOMY

‘All the . . . country produces . . . every kind of livestock’.1 The domestication of farm animals by humans can be traced back, in parts of the Old World, to around 5000 BC.2 By the beginning of the Iron Age, in the eighth century BC, the peoples of temperate Europe had a diverse economy which included cereal and garden cropsand the rearing of animals, particularly cattle, sheep, pigs and horses.3 This mixed farming has been afeature of many, ifnot most, of past European societies.4

There is no doubt that intensive husbandry of animals was practised in both Gaul and Britain during the Celtic Iron Age. The Celts were so good at stock-raising that the Greek geographer Strabo had occasion to comment:‘They have such enormous flocks of sheep and herds of swine that they afford a plenteous supply of sagi [woollen coats] and salt meat, not only to Rome but to most parts of Italy’.5 The vernacular sources of Ireland and Wales show us a Celtic society which relied on its cattle, sheep and pigs and in which a cow or a pig represented wealth.

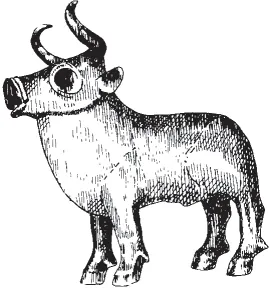

Figure 2.1 Bronze figurine of a bull, sixth century BC, Býciskála Cave, Czechoslovakia. Height: 11.4cm. Paul Jenkins.

We have a problem in attempting to assess the stock-rearing aspect of farming during the Iron Age because almost all our information necessarily comes from bones, and these are notoriously difficult to interpret. For example, much bone waste from homes and farms has either been destroyed by acid soils or has been comminuted by the gnawing of dogs and pigs, with the result that the smaller, more fragile, bones of fish, chickens and very young animals have often vanished from the archaeological record.6 Again, there are very few good bone reports from modern excavations: none the less, in Britain we benefit from the exhaustive bone reclamation from Danebury (Hants) and Gussage All Saints (Dorset) and their careful respective analyses by Annie Grant and Ralph Harcourt. For northern France, the work of Patrice Meniel and Jean-Louis Brunaux has enhanced considerably our knowledge of Iron Age pastoral farming.

There is a peculiar relationship between humans and animals, a rapport born of the many features they have in common.7 Domestic animals lived and worked in a close and symbiotic association with humankind. They were tended, protected and fed but this caring was the means to a productive and profitable end – whatever was useful to humans. In a pastoral farming community, every part of an animal may be utilized: milk, wool, manure and muscle (for traction or transport) when it is alive; hides, meat, fat, blood, sinew and bone when it has been slaughtered.

There are certain general characteristics of Celtic domestic beasts and their use in Gaul and Britain. One is the small size of cattle, sheep, pigs and horses relative both to Roman strains and to present-day species.Larger, improved animals were present by the later Iron Age, possibly because of Roman influence but also perhaps because of better nutrition.At the time of the Roman occupation, both Gaul and Britain necessarily intensified their cereal production, giving cattle better fodder from the cereal waste and, at the same time, better pasture had been available by the later Iron Age because heavier soils, yielding lusher grass, were being exploited.8 A second feature of animal utilization has been the use of beasts in ritual activity (see chapter 5). A third is the very limited use made of wild animal resources for food (see chapter 3). Hunting was practised but was clearly not a significant source of food. An exception to this trend may have pertained at Val Camonica in northern Italy, where the evidence of the rock art – if it is a true reflection of daily life – suggests that stock-rearing played a very secondary role to hunting.But even here, pastoral farming clearly fulfilled the basic needs of the Celtic Camunians, for meat, eggs, dairy products, leather and wool.9 Some Iron Age sites used all the natural resources available to them: thus, at the Glastonbury lake village wading-birds and fish were caught, in addition to the raising of sheep for their meat and wool.10 Athenaeus tells us that the Celts who lived near water ate fish11 which they baked with salt and cumin.

PASTORAL FARMING AND STOCK MANAGEMENT

Generally speaking, the most common animals to be found on Celtic farms were cattle, sheep, pigs and horses. In addition, there is evidence of goats, ranched deer, farm dogs (used as guard dogs, sheepdogs and waste-scavengers) and cats to keep down vermin. But within this general scenario, there were certain differences between settlements, and changes occurred through time. An interesting view of hillforts is that the function of some may have been either wholly or partially as stock enclosures.12 Thus in the late period of Danebury (between 400 and 100 BC) the middle earthwork may have been added to form an enclosure or paddock for the protection of stock. When the outer earthwork was built, additional corralling space became available: this represents either an alteration in the system of farming in the latest phases of the hillfort, the existence of larger flocks and herds, or possibly increased tension resulting in the need for greater protection for stock.13 Certainly by the first century AD stock enclosures were a feature of a great many Iron Age farmsteads in Britain,14 and this may reflect an increasing population with a consequent ...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FIGURES

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- 1: THE NATURAL WORLD OF THE CELTS

- 2: FOOD AND FARMING: ANIMALS IN THE CELTIC ECONOMY

- 3: PREY AND PREDATOR: THE CELTIC HUNTER

- 4: ANIMALS AT WAR

- 5: SACRIFICE AND RITUAL

- 6: THE ARTIST’S MENAGERIE

- 7: ANIMALS IN THE EARLIEST CELTIC STORIES

- 8: GOD AND BEAST

- 9: CHANGING ATTITUDES TO THE ANIMAL WORLD

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY