eBook - ePub

Towards the Museum of the Future

New European Perspectives

- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Towards the Museum of the Future

New European Perspectives

About this book

Towards the Museum of the Future explores, through a series of authoritative essays, some of the major developments in European museums as they struggle to adapt in a rapidly changing world. It embraces a wide range of European countries, all types of museums and exhibitions and the needs of different museum audiences, and discusses the museum as communicator and educator in the context of current cultural concerns.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Towards the Museum of the Future by Roger Miles, Lauro Zavala, Roger Miles,Lauro Zavala in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Museum Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

New Worlds

New Worlds

Europe has seen a phenomenal resurgence in the building of museums during the 1970s and 1980s, exactly one hundred years after the last great boom which gave us, among many others, the magnificent buildings of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (1876), the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (1885), and the Grande Galerie de Zoologie of the Natural History Museum in Paris (1889). We have long ago lost the certainty that neoclassicism is the ‘correct’ style for museum buildings, despite its ghostly reappearance in recent work such as the Sainsbury Wing of London’s National Gallery. Ian Ritchie discusses in Chapter 1 the recent boom in new buildings and major refurbishment programmes in terms of today’s pluralism in architecture as, throughout Europe, key cities compete to establish their individual identity through museum culture.

‘Identity’ has become a keyword in the way museums present themselves in today’s complicated world, in which museum functions have also become increasingly complex. Ruedi Baur, Pippo Lionni and Christian Bernard discuss the role of a graphic identity in establishing a corporate spirit, which serves both to unify diverse functions within a museum and to present them as a coherent whole to the outside world. This leads them to views on the relationships between the museum as image, container and contents – central concerns of Ian Ritchie’s contribûtion – that signal continuing debate on the proper balance between these aspects of museums and their functions. These are long-standing topics of discussion which, it seems, recent developments in Europe have done nothing to resolve, and may even have exacerbated. The subject is taken up by Jan Hjorth in Part 2 of this book (Chapter 7), with the thought that exhibitions, if they are not to abuse their visitors, should strike a balance between education and design.

Despite the construction of many new buildings, perhaps more than half of Europe’s museums are housed in buildings that originally served other functions. There is a touching belief among planners and architectural historians that almost any redundant building can be made usable, and therefore ‘saved’, by converting it into a museum. Enthusiasts wishing either to start up or expand a museum, and having no money to do otherwise, are forced to go along with this notion, notwithstanding the problems it causes them. Thus science centres (though there are a few outstanding exceptions such as Heureka in Finland) have generally, on account of their financial precariousness, had to house themselves where they can. Nevertheless, as Melanie Quin makes clear in Chapter 3, science centres have developed with great vigour in Europe over the last ten years, propelled by the example of the United States and a concern for the public understanding of science. Their strong community spirit, reflected in the sharing of ideas and in the formation of ECSITE (European Collaborative for Science, Industry and Technology Exhibitions), contrasts strongly with the situation among more traditional museums, where separate development is still the order of the day.

The heritage debate centres on English attempts to turn history into an experience, to make the past knowable by, characteristically, making displays out of the people as well as for the people. England, with its huge voluntary membership of the National Trust and its official conservation body, English Heritage, and with its new cultural ministry, the Department of National Heritage, provides fertile soil for this approach and for the critical discussion that has come with it. As Robert Lumley explains, ‘heritage’ served as a metaphor for England’s troubled identity in debates of the 1970s and 1980s (see Chapter 4). However, it would be wrong to view this as a uniquely English subject, for questions about the presentation of history to serve political and ideological purposes are never far below the surface in museums, regardless of type or country. This is particularly true of open-air or folk museums which, since their origins in Scandinavia (Skansen in Stockholm dates from 1891), have spread throughout Europe, and in which, in former Soviet-bloc countries such as Yugoslavia and Rumania, folk culture was celebrated to keep alive a sense of national identity. Europe’s many current uncertainties over nationalism and nationality suggest that the heritage debate has far to run.

1

An Architect’s View of Recent Developments in European Museums

Introduction

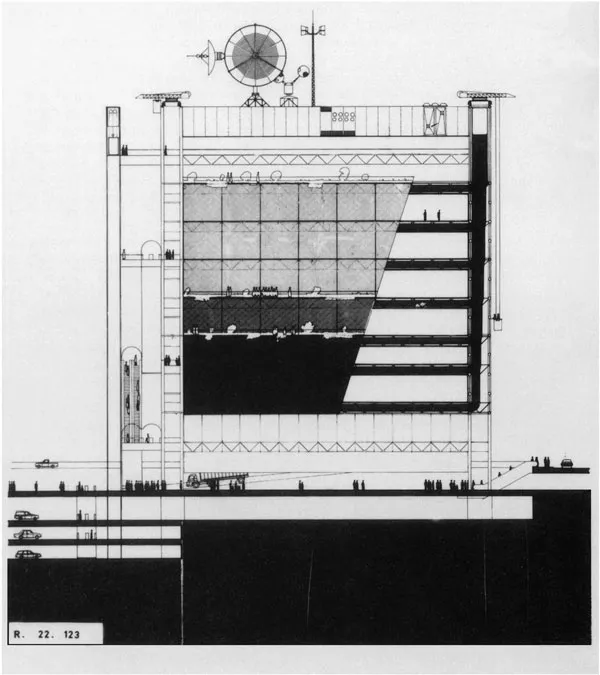

There is little doubt that the Pompidou Centre in Paris (Figure 1.1), 1972–7, represented a dramatic shift in museum design and the image of museums in contemporary cultural life. Conceived as a technically and spatially flexible container for art, books, research and exploration, it provided, on an enormous scale, the opportunity for virtually any cultural content to be housed, including small objects, paintings, sculptures, site happenings, music, etc. This approach produced very large floor plates, whose intrinsic spatial characteristics were uniform although far from ‘neutral’, with the presence of the large-span beams and colour-coded servicing elements dominating the spaces.

Figure 1.1 Pompidou Centre, Paris

However, this internal architecture was not necessarily the most significant aspect of the Pompidou Centre. The very nature of its entrance and its celebratory escalators took away the ‘front steps’ to high culture. It was, in its very essence, populist and freely accessible, and the strength of the public piazza in front of the building gave additional emphasis to the informality of the concept. There was no longer any notion of having to be ‘educated’ to participate in culture. The polemic created by the Pompidou Centre was not only architectural but also political. It represented the beginning of a renaissance in French government policy towards expressing belief in its own time and culture. This renaissance is still active today, having enjoyed the support of three French Presidents, opposing political parties in government, and the introduction of a certain autonomy for Paris through the re-establishment of the City Council and role of the Mayor. This renaissance is significant in as much as Paris was already, together with London and New York, a traditional centre of museum culture.

In 1978 the city of Frankfurt, co-ordinated by the Mayor Walter Wallman and the two main political parties (the Social Democrats (SPD) and the Conservatives (CDU)), agreed to redefine the image of Frankfurt and to promote the city as being much more than a financial centre. The key component of this change was the renewal of the urban landscape, into which would strategically be placed cultural institutions. Within the following decade, thirteen such institutions have been conceived, often by internationally renowned architects, and not without controversy.

This city of 500,000 people, in spending 11.5 per cent of its budget on culture, succeeded in transforming and enhancing its urban fabric and in completely changing the international perception of Frankfurt. Thus Frankfurt has, more than any other European city not previously a cultural centre, influenced through political will other non-capital European cities to invest in culture, and in particular in museums. This phenomenon has swept through Spain and, to a lesser but still significant degree, Italy. It is perhaps pertinent to ask why, in the last decade or so, European cities, one after the other, have decided to invest in museums. It is clear that these cultural typologies have become the kings, queens and sometimes aces in each city’s hand as they vie with each other across Europe (and the world) for attention. France, largely through its museums, has been in the vanguard in implementing a ‘cultural industry’, first and foremost in Paris, but also in the provinces.

Thus three factors – the need for cultural facilities responding to our own age; the desires and quest for public awareness of recent cultural developments; and the desire for national and capital identity in a rapidly shrinking world – have also created an industry in both an economic and social sense. France, recognising the tendency of a leisure-orientated society in the 1960s along with many other western countries, constructed a coherent strategy which has resulted in Paris remaining at the top of the world’s cultural capitals; its major provincial cities emerging strengthened in the wider European context and its smaller towns sharing in the cultural facilities boom of the 1980s.

It is certainly the European context which has become the challenge for many cities. Europe, whose identity is an ongoing accident of history, is in a sense no longer an embryonic community of countries, but has become one of the world’s primary geographical zones, in which the principal players are now, and in the foreseeable future, the cities within it. The political power of the elected mayors in France, Germany and Spain, married with their respective visions to improve the quality of life, has led to the combination of urban design and public buildings as a major vehicle to carry forward these political objectives into reality.

New Museums

To place in perspective the recent developments in museum design, it is first necessary to recall, with a precise but brief note, the development of European museums up to recent times. In essence, they began with collections, and if we go far back to the sacking of Corinth (AD 146) and Syracuse (212), the plundering of artefacts was on such a scale that apparently an entire area of Rome was set aside for trade in these art objects. This trading inevitably led to the arrival of collectors. It is the collector who began the process which led to the notion of museums. It is equally true that the nature of the collections subsequently conditioned the physical and spatial qualities of the buildings in which to house them. There is no denying that museums initially evolved as a result of the individual collector’s wishes and demands, and not those of the public who first came to visit these collections. Initially, these collections were in ‘houses’ (for example, Medici in Florence, François I in Paris). As their collections grew, the ‘professional curator’ appeared (Donatello at the Medici’s, Leonardo da Vinci in Paris). In 1780, Grand Duke Leopold brought together the extensive Medici collections at Uffizi, which was opened to the general public in the 1830s (Leopold II), at which time it took the name Museo degli Uffizi. The physical nature of the display space at the Uffizi was a series of corridors. Throughout Italy during the early 1800s, the ‘grand families’ of Italy (e.g. the Borghese, Franese in Rome, the Dorias in Genoa, Este in Ferraza, etc.) vied with each other through the qualities and size of their respective collections which embellished their palazzi. Each in turn found the necessity to create a ‘display nucleus’ – gallery(ies), curator, restorer and collector. This nucleus is essentially still present today.

In parallel, in England, notable families were behaving in a similar way; and in 1757 the British Museum opened in Montague House. It was an assembly of private collections made over to the realm. Only after this stage did the very first signs of purpose-designed galleries appear: Sir John Soane’s Dulwich Gallery (1814) and Sir Robert Smirke’s British Museum (1823). A number of European capitals enlarged their ‘houses’ or ‘palaces’ with specific galleries (e.g. the Egyptian Wing of the Louvre, 1823) over the next few decades. In fact, the desire of the educated European to visit these collections became insatiable. The museum had arrived, and was a place where you studied and learnt from the past.

It was in 1851, with the Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, that the first ‘display’ (and on a huge international scale) of the present with suggested interpretations for the future first appeared. This was very significant in that it was a purpose-designed public exhibition space which did not have the decorated facades of classicism, which had already been the ‘norm’ with public museums and galleries during the nineteenth century (Figure 1.2). I suggest that because of the historical nature of the museum collections, a classical architectural facade in front of enfilades of rooms and corridors was deemed culturally appropriate. In fact, the world exhibitions that followed in Paris (1867), Philadelphia (1876) and Paris again (1878) illustrated very clearly through their pavilion buildings an architectural taste for style, often quite independent of the contents on display. National identity was often expressed through each pavilion’s architecture.

...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Frontmatter page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Photographic Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1 New Worlds

- 1 An Architect's View of Recent Developments in European Museums

- 2 Some General Thoughts on Corporate Museum Identity The Case of the Villa Arson, Nice1

- 3 Aims, Strengths and Weaknesses of the European Science Centre Movement

- 4 The Debate on Heritage Reviewed

- Part 2 New Services

- 5 Visitor Studies in Germany Methods and Examples

- 6 Families in Museums

- 7 Travelling Exhibits The Swedish Experience

- 8 ‘Why are you Playing at Washing up Again?' Some Reasons and Methods for Developing Exhibitions for Children

- 9 Museum Education Past, Present and Future

- Part 3 New Analyses

- 10 The Rhetoric of Display

- 11 The Medium is the Museum On Objects and Logics in Times and Spaces1

- 12 Some Processes Particular to the Scientific Exhibition

- 13 The Identity Crisis of Natural History Museums at the End of the Twentieth Century

- Index