- 180 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Architecture and Technology

About this book

Many books have covered the topics of architecture, materials and technology. 'New Architecture and Technology' is the first to explore the interrelation between these three subjects. It illustrates the impact of modern technology and materials on architecture.

The book explores the technical progress of building showing how developments, both past and present, are influenced by design methods. It provides a survey of contemporary architecture, as affected by construction technology. It also explores aspects of building technology within the context of general industrial, social and economic developments. The reader will acquire a vocabulary covering the entire range of structure types and learn a new approach to understanding the development of design.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Trends in architecture

1.1 An Overall Survey

Architectural styles and trends have been discerned and described ever since ancient times. The objective of this chapter is to build on this tradition by describing these trends while placing particular emphasis on the second half of the twentieth century. Whilst other chapters will be dealing with the technological aspects and diverse specific areas of architecture, this one will focus on the changes in architectural styles, but not at the expense of ignoring the corresponding technical, aesthetic, social and other influences. The intention is not to compile a comprehensive history of architecture, and the chapter is restricted to aspects relevant to the subject of the book: to the impact of technological progress on new architecture. For expediency, the discussion is divided into three 40-year periods: 1880–1920, 1920–60 and from 1960 to the present. As the subject of this book is contemporary architecture, the first period will be discussed only in perfunctory terms. More emphasis will be given to the second one, and still greater detail to the final and most recent period.

Whilst this book is devoted to the contacts between architecture and technology, one should not forget the other aspect of architecture as being also an art, indeed one of the fine arts. It has in particular a close affinity with sculpture. In some stylistic trends (for instance in the Baroque and in the Rococo) the division between these two branches of art was scarcely perceivable. In modern times architecture was more inclined to separate itself from sculpture although certain (e.g. futurist) sculpture did receive inspiration from modern architecture. Later, during post-modern trends, sculpture again came close to architecture so that some architectural designs were conceived as a sculpture (Schulz-Dornburg, 2000). However, in all that follows in this book we focus attention on the interrelationship of (new) architecture and technology.

On the other hand, up-to-date (high-tech) technology may be directly used for new forms of architectural art. Such forms, as for example the application of computer-controlled contemporary illumination techniques, are part of the subject matter of this book and will be discussed at the appropriate place.

1.1.1 The period 1880–1920

It was this period that saw the end of ancient and historical architectural styles, such as Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Byzantine and the later Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, thus paving the way for twentieth-century modernism. Independence was achieved by what were former colonies as, for example, in Latin America. The benefits of scientific revolution and industrial development were reaped mostly by the leading powers of the day: Great Britain, the United States, France, Germany and Japan. Their conflict resulted in the First World War of 1914–18. At the end of this war it seemed that society was being impelled by democracy and the ideas of liberal capitalism and rationalism, and it was hoped that scientific and economic progress would provide the means for solving the world's problems.

During this 40-year period the construction industry progressed enormously. Even earlier in the 1830s, railway construction was expanding at first in the industrialized countries, later extending to other parts of the world. The growing steel industry provided the new structural building material. A few decades later, the use of reinforced concrete began to compete with steel in this field.

Figure 1.1 The Eiffel Tower, Paris, France, 1887–89, structural design: Gustave Eiffel, 300 m high. One of the first spectacular results of technical progress in construction. © Sebestyen: Construction: Craft to Industry, E & FN Spon.

The progress in construction during this period was perhaps best symbolized by the Eiffel Tower, designed by Gustave Eiffel (1832–1923) (Figure 1.1), a leading steel construction expert of his time. In fact, the Tower was built for the Paris World Exhibition in 1889 and the intention at the time was that it should be only a ‘temporary’ exhibit. Originally 300 metres high, it was taller than any previous man-made structure. More than a century later, during which it has become one of the best-loved buildings in the world, it is still standing intact.

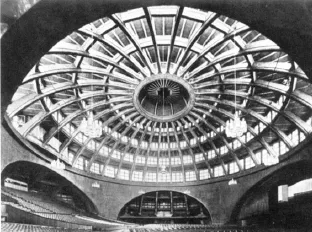

A subsequent engineering feat was the Jahrhunderthalle in Breslau (now Wroclaw), designed by Max Berg (1870–1947) (Figure 1.2), and completed in 1913, a ribbed reinforced concrete dome, which, with its 65-metre diameter, was at its time of construction the largest spanning space yet put up in history. In this heroic period, such technical novelties as central heating, lifts, water and drainage services for buildings became extensively used.

In architecture and the applied arts, there were attempts to revive historical styles, such as the neo-Gothic and neo-Renaissance. Later, the mixture of these historical styles and their reinterpretation gave rise to the Art Nouveau or Jugendstil movements, collectively known as the ‘Secession’, which literally meant the abandonment of the classical stylistic conventions and restraints. A similar style was propagated in Britain by the designer William Morris (1834–96), and in America by his followers, in the Arts and Crafts movement, whose aim was to recapture the spirit of earlier craftsman-ship, perhaps as a reaction to the banality of mass production engendered by the Industrial Revolution. Consequently, a schism occurred amongst artists, designers and the involved public, between those who advocated adherence to the old academic style and tradition and ‘secessionists’, who favoured the use of new techniques and materials and a more inventive ‘free’ style. Also during this period some architects, both in Europe and America, began to experiment with the use of natural, organic forms, such as the Spaniard Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926) in Barcelona and the American Frank Lloyd Wright (1869–1959) (Plates 1 and 2); the latter; in addition, drawing on local rural traditions and forms. Amongst European protomodernists, the Austrian Adolf Loos (1870–1933), the Dutchman Hendrik Petrus Berlage (1856–1934) and the German Peter Behrens (1868–1940) merit mention. Using exaggerated plasticity and extravagant shapes, the German Erich Mendelsohn (1887–1953) and Hans Poelzig (1869–1936) were important figures in the lead into modern architecture.

Figure 1.2 Jahrhunderthalle, Breslau (Wroclaw), Germany/Poland, 1913, architect: Max Berg. The first (ribbed) reinforced concrete dome whose span (65 m) exceeds all earlier masonry domes. © Sebestyen: Construction: Craft to Industry, E & FN Spon.

1.1.2 The period 1920–60

Early modernism

The period has been defined as the period of ‘modernism’, when architecture finally broke completely with tradition and the ‘unnecessary’ decoration. With the end of the First World War in 1918, the traditional authority and power of the ruling classes in Europe diminished considerably, and, indeed, in some cases was completely eliminated through revolutions. Even in the victorious nations, such as France and Britain, the loss of life and sacrifice on a vast scale amongst ordinary people fuelled resentment against the establishment.

Germany, having lost the war, was in turmoil and the Austro-Hungarian monarchy ceased to exist altogether. In consequence, the political and economic realities of the time in Europe and elsewhere were most conducive to breaking with tradition, and in this, architecture was no exception.

In Europe, the first focal point of the new aesthetics, modernism, was the school of design, architecture and applied art, known as the Bauhaus, founded by Walter Gropius (1883–1969) in 1919 in Weimar, Germany. Whilst adopting the British Arts and Crafts movement's attention to good design for objects of daily life, the Bauhaus advocated the ethos of functional, yet aesthetically coherent design for mass production, instead of focussing on luxury goods for the privileged elite. Gropius engaged many leading modern artists and architects as teachers, including Paul Klee, Adolf Meyer, Wassily Kandinski, Marcel Breuer and László Moholy-Nagy, just to mention a few.

The early Bauhaus style is perhaps best epitomized by its own school building at Dessau, designed by Walter Gropius in 1925, a building of a somewhat impersonal and machined appearance. Gropius was succeeded as Director by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) in 1930. Perhaps his best works of the period were the German Pavilion for the International Exhibition at Barcelona and the Tugendhat House at Brno, Czech Republic in 1929 and 1930 respectively. Mies van der Rohe can be counted as one of those architects who genuinely exercised a tremendous influence on the development of architecture. His Tugendhat House influenced several glass houses (Whitney and Kipnis, 1996). We can also see his influence on the architecture of skyscrapers and other multi-storey buildings.

In the Netherlands, influenced by the Bauhaus, but also contributing to it, Theo van Doesburg, Gerrit Thomas Rietveld and Jacobus J. Oud were members of the ‘De Stijl’ movement, which itself was influenced by Cubism. Their ‘Neoplastic’ aesthetics used precision of line and form. The culmination of early Dutch modernism was perhaps Rietveld's (1888–1964) Schröder House, built in 1924 at Utrecht (Figure 1.6).

In France the most influential practitioner of modernism was the Swiss-French architect Charles Edouard Jeanneret, universally known as Le Corbusier (1887–1965). His early style can best be seen in the two villas: Les Terrasses at Garches (1927) and the Villa Savoye at Poissy (1930), where the floors were cantilevered off circular columns to permit the use of strip windows. Flowing, plastically-modelled spaces and curved partition walls augmenting long straight lines characterize both buildings. Le Cor-busier also influenced the profession through his theoretical work Towards a New Architecture published in 1923 as well as through his activity abroad and in international professional organizations. The creation of the CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne) in 1928 underpinned the movement towards modernism, industrialization and emergence of the ‘International Style’.

A realization on an international scale of this trend was the residential complex in Stuttgart, Germany, in which seventeen architects participated. Gradually, in several European countries modernism became dominant. Some of the countries in which eminent representatives were to be found (e.g. France, Germany, Great Britain and the Netherlands) receive mention later; while other countries (e.g. Italy) although not cited directly had equally outstanding architects.

Along with the aesthetic transformation of architecture, technical progress was also remarkable, and nowhere more so than in the United States, where in the late 1920s, following the achievements and examples of the Chicago School some 25 years before, there was a further period of boom in the construction of skyscrapers. The Empire State Building in New York, designed by architects Shreve, Lamb and Harmon, completed in 1931, symbolizes what is best from this period. With its 102 storeys and a height of 381 metres, it remained for 40 years the tallest building in the world. Another construction of great symbolic value was the Golden Gate Bridge at San Francisco, California. This is a suspension bridge with a span of 1281 metres and was completed in 1937.

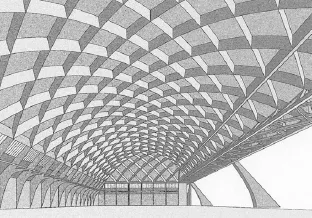

Meanwhile in Europe, wide-spanning roofs were constructed without internal support by a new type of structure: the reinforced concrete shell based on the membrane theory. The Planetarium in Jena, Germany (constructed between 1922 and 1927), with a span/thickness ratio of 420 to 1 is a prime example. Additionally, wide-spanning steel structures (space frames, domes and vaults) were developed.

Figure 1.3 Airplane Hall, Italy, designer: Pier Luigi Nervi, 1939–41, floor surface 100 [H11003] 40 m, vault assembled from pre-cast reinforced concrete components. An early (pre-Second World War) example of prefabrication with reinforced concrete components. © Sebestyen: Construction: Craft to Industry, E & FN Spon.

The promising economic progress of the 1920s received a severe jolt in 1929 as a result of the worldwide economic crisis that was to last for about three years. Although by the early 1930s there was again an upswing in the economy, new political events affected the course of modern architecture. Germany, as had Italy several years earlier, became a fascist dictatorship in 1933. Modernism, however, was an anathema to ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Trends in architecture

- 2 The impact of technological change on building materials

- 3 The impact of technological change on buildings and structures

- 4 The impact of technological change on services

- 5 The impact of invisible technologies on design

- 6 The interrelationship of architecture, economy, environment and sustainability

- 7 Architectural aesthetics

- 8 The price of progress: defects, damages and failures

- 9 Conclusion

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access New Architecture and Technology by Gyula Sebestyen,Christopher Pollington in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.