![]()

1

JUSTICE IN AND TO THE ENVIRONMENT

Never allow yourself to be swept off your feet; when an impulse stirs, see first that it will meet the claims of justice.

(Marcus Aurelius, Meditations)

INTRODUCTION

Justice is no mere abstraction. Finding justice and doing justice is a continuous human task. It is the activity which in any society gives politics and the law their purpose. The activity has both a material and a discursive dimension. It has to do with what we are, what we do and what we say. What we are and do is materially real. How we relate to others is discursively real, a matter of communicated explanations via words. The struggle for justice is about how we explain the basis of a good and proper relationship between ourselves and others. In defining this relationship we define who and what we are and who and what ‘the other’ is.

This task is continually expanding as new actors enter the struggle: new perspectives are inscribed in the debates, new problems are defined for society, in short, as politics in the broadest sense takes new forms. The question of justice is today being reshaped by the politics of the environment. For the first time since the beginning of modern science we are having to think morally about a relationship we had assumed was purely instrumental. In the ancient world humans were seen as the instruments of nature or ‘the gods’. In the modern world the position was reversed; a disenchanted ‘nature’ became an infinite pool of resources to be made into things of use to us. Today the relationship between humans and the rest of the natural world is again being redefined. At the precise moment when it became clear that we humans had this planet in the palm of our hand, it also became clear that we are likewise held by it. Just when we became free and separated from the earth we discovered the nature of our attachment to it.

The word ‘environment’ today seems scarcely adequate to describe that to which we are attached. The planet, and indeed the universe, seems much more than the surroundings of a human person to be defined only in relation to the human. Yet our experience of nature is necessarily localised. Even from space a person may view the planet Earth as a whole but interact mostly with the little bit of nature she takes with her as ‘life support’. We experience our own small part of ‘nature’ which we look out on, interact with, breathe, eat, drink, touch, hear and smell. This is our environment. It can be very good for us or very bad. Some people live and work in delightful environments. Others exist in oppressive and ugly environments. For some what was once a harmonious and healthy relationship with their environment is transformed suddenly into a risky and dangerous one.

Who are ‘we’? There are two meanings of ‘we’: ‘we the people’ and ‘we humans’. ‘We the people’ are always defined by a place within humanity, both social and geographical. So there is a distributional question: who gets what environment – and why? As to ‘we humans’, there are qualities we share as a species, and we humans have now to consider our relationship with the non-human world. The struggle for justice as it is shaped by the politics of the environment, then, has two relational aspects: the justice of the distribution of environments among peoples, and the justice of the relationship between humans and the rest of the natural world. We term these aspects of justice: environmental justice and ecological justice. They are really two aspects of the same relationship.

SITUATING JUSTICE

We take an approach which situates the discussion of justice in actual events. Many texts on environmental ethics begin by posing questions which assume a societal, or even global, frame (Hardin, 1968; Commoner, 1972; Drengson, 1980; Tokar, 1987; Spretnak and Capra, 1986; Sessions, 1989). These ‘big questions’ commonly address: the capacity of the earth’s resources to support its human population; the capacity of the biosphere to absorb human wastes; climate change as a result of human agency; the rapidly increasing rate of extinction of non-human species; the exploitation of the environment of the poorer nations to maintain the lifestyle of the richer; the systematic discounting of the interests of unborn generations; the massive injury to the forests and seas; and the industrial use of animals. Conclusions are then drawn about the kind of society and morality we have to develop to prevent these things happening: the society of ‘our common future’ (Brundtland Report, 1987).

Ultimately, political and environmental ethics must address this ‘big picture’ because so many ecological and social problems have a systemic or structural basis. We need political–ethical frameworks which can help humanity to address those threats which it faces collectively. Nevertheless, if the struggle for justice is a real world process then we must make clear how abstract conceptions are connected with real world events. Threats to the environment, however global, are manifested in specific places and local contexts. If society is to change to accommodate new conceptions of justice, it is necessary to demonstrate in an immediate and concrete way why the existing means of dealing with environmental conflicts are inadequate. Social change on the scale which may well be necessary for global society to carry on the task of finding and delivering justice in and to the environment is likely to proceed in a somewhat piecemeal and incremental way. However, incremental change, as we have seen repeatedly in this century, can have far-reaching consequences (Swyngedouw, 1992).

Our point of departure, then, is not the big picture of ‘our common future’, but examples of actual and public conflicts over the environment. The broader struggle against social forms which produce environmental injustice, biospheric destruction and the maldistribution of environmental risk begin as engagements with specific conflicts.

In 1995 three incidents occurred which tell us something about the nature of environmental conflict. These incidents are a small and not necessarily representative sample of the many reported and unreported cases of exploitation which, taken together, present a threat to the ecological integrity of the planet. They are the kinds of issues on which, in one way or another, judgement is passed. The first was the unsuccessful attempt by the Anglo-Dutch transnational corporation, Shell, to sink one of its obsolete oil rigs in the North Atlantic; the second was the conduct by France of a series of underground nuclear tests in Pacific atolls; the third was the mining of metallic ores by the Australian transnational corporation Broken Hill Pty Ltd (BHP) in Papua New Guinea.

Disposal of the ‘Brent Spar’

When oil-drilling rigs become obsolete their owners must find a way of disposing of them. The first Norwegian rig to be decommissioned had been brought ashore for dismantling. But Shell, the joint owner with Exxon (Esso), decided it would dispose of the British Brent Spar rig by towing it out into the North Atlantic and sinking it in deep water. Shell obtained approval from the British government for the dumping. But there are many oil rigs around the world which are reaching the end of their life, and the principle of dumping at sea was vigorously opposed by the green movement in Europe. The rig is a steel and concrete tube the size of an upended aircraft carrier. The main environmental hazard is allegedly caused by the oil waste and radioactive scale contained in the tanks. It was feared these poisons would eventually seep out into the sea.

The international activist organisation, Greenpeace, launched a political campaign including a consumer boycott in Europe aimed specifically at Shell. The main focus of the campaign was Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands. Governmental action in Europe was mobilised around the Oslo and Paris Conventions which regulate the disposal of waste into the North Sea. The 1972 Oslo Convention covers the prevention of sea pollution by dumping from ships and aircraft, and the 1974 Paris Convention covers the prevention of marine pollution from land-based sources. These Conventions were drawn up within the framework of the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

The consumer boycott had an immediate effect on Shell’s fuel sales, which slumped by 30 per cent, and the company was dismayed by the tarnishing of its carefully cultivated image of environmental responsibility. This image was, however, finally ruined in late 1995 by the publicity given to the company’s involvement with the Nigerian government in the violent suppression of protest against Shell’s environmental degradation of the land of the Ogoni people of Nigeria.

Intergovernmental action in Europe led by the German government, rather than the consumer boycott, was probably in the end decisive. The German government, applying the precautionary principle, insisted that the risk was substantial (Johnson and Corcelle, 1989: 294–5 and 301).

On 21 June, at the very moment that the British Conservative Government was stoutly defending Shell in Parliament, Shell capitulated to the political and consumer pressure and the tugs towing the rig turned around, providing a powerful visual symbol of victory for the green campaign. Greenpeace won this battle, but the vast oil rig still has to be disposed of. It is true that disposal on land may render the process more open to scrutiny, but whether the process will create any less pollution of the air, soil or water remains to be seen. Even if the process of disposal is potentially open to public scrutiny, it will most probably not attract the media attention brought to bear on the single dramatic event of a sinking at sea. The focus of the issue was the distribution of risk rather the production of risk (Lake and Disch, 1992; Dryzek, 1987), a critical ecological distinction which we will address in Chapter 5.

Paradoxically the great political triumph of Greenpeace was later acknowledged by that organisation to have been of doubtful value to the environment. In the rapid mobilisation of opposition, accurate information was in short supply. The representation of risk became the principal objective of those opposed to the dumping. Greenpeace retreated from its earlier position that marine disposal of the rig posed a threat to the environment. Whatever the actual risks involved may or may not have been, they were never subjected to careful examination and judgement. Winning the battle became an end in itself.

French nuclear tests in the Pacific

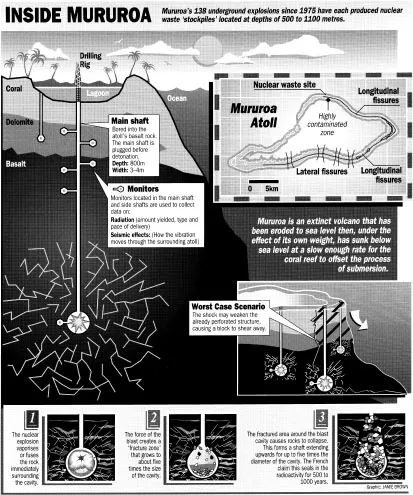

On 7 September 1995 the French government carried out the first of six nuclear tests on Mururoa and Fangataufa atolls in the Pacific. The French Prime Minister said, ‘the nuclear tests will incidentally (sic) not have any impact on the environment because they are carried out at very great depths in solid rock’. Other experts disagree. The French newspaper, Le Monde, has published photographs reportedly taken by French divers in Mururoa lagoon in 1987 which show cracks three metres wide and several kilometres long in the volcanic structure. Pierre Vincent, the French vulcanologist, considers it possible that a flank of the basalt rock below water level could shear off and fall into the sea. The evidence suggests that such shearing is a normal event in volcanic explosions as was demonstrated when Mount St Helens exploded and the north flank of the mountain broke away. Computer simulations carried out in New Zealand suggest that radiation may already be leaking into the sea through cracks in the basalt, and will in any case do so sometime in the next hundred years (Cookes, 1995). Dr Tilman Ruff, a physician at the International Health Unit of the Macfarlane Burnet Centre for Medical Research, Melbourne, writes that there is:

clear evidence, documented by the brief and limited independent scientific and medical missions that have visited French Polynesia, of extensive damage to Mururoa; venting and early indications of long term radioactive leakage from underground nuclear explosions; well documented outbreaks of ciguetera fish poisoning caused by the nuclear test program; and adverse social effects of nuclear colonialism.

(Ruff, 1995; see Figure 1.1)

Whether or not actual damage to the atolls has yet occurred, whether or not the islands are yet leaking radiation, there is a very definite risk, indeed a probability, that radiation will escape in future. Ulrich Beck (1995) has observed that the discourse over the environment is primarily a discourse of risk. The experience of a nuclear accident at Chernobyl has alerted the world to the devastating and widespread effects of a nuclear leak into the environment. Even if the risk is small, the disaster risked is enormous. It is all the more shocking that the military nature of the test programme makes adequate public scrutiny of the risk impossible. No sanctions are available which would make the national interest coincide with the global interest. The evidence cannot emerge to provide any test of truth about present damage. Protests from other nations, the opinion of French people, and pressure from non-government organisations had little immediate impact. The French government stopped testing when it suited the French government.

Of course, reasons of state supplement reasons of the economy. France’s continued development of nuclear weapons supports a nuclear industry situated in Monsieur Chirac’s particular constituency, the Paris region (Chirac was the first Mayor of Paris, and still occupies that position in addition to the presidency). The nuclear tests were to result in the final certification of the warhead of the M 45 multi-warheaded missile carried by a new generation of nuclear submarines, the SNLE-NG (Ruff, 1995). Australia, while protesting loudly in public, sells uranium ore to France which is used in the French nuclear reactors which produce the fuel for the nuclear devices.

Figure 1.1 French nuclear tests: inside Mururoa Atoll

Source: Detail from a diagram by Jamie Brown, published in The Age, Melbourne, 12 August 1995

Mining in Papua New Guinea

Since the mid-1970s the Australian mining corporation, BHP, in close co-operation with the government of Papua New Guinea has developed one of the biggest open-cut copper and gold mines in the world. The Papua New Guinea government has taken a 30 per cent equity stake in the mine. The mine is at Mount Fubilan in the northern mountains near the source of the Tedi river (Ok Tedi). Ok Tedi is part of Papua New Guinea’s biggest river system, the Fly River, which flows into the Gulf of Papua. The mine has gouged an enormous crater in the mountain, destroyed the local rain forest and discharges about 80,000 tonnes of limestone sludge per day into the upper reaches of the Ok Tedi (see Figure 1.2). The sludge contains many chemicals and minerals including copper particles in concentrations of up to 18 per cent of the waste.

Since mining began in the mid-1980s, over 250 million tonnes of waste have been dumped into the river. During the wet season, when river levels rise very quickly, an impervious blanket of mine sediment is deposited on the forest floor downstream. In places this blanket is more than a metre thick. For about thirty square kilometres along the river flood plain, the forest has died. The Government of Papua New Guinea has admitted that the environmental damage cannot be repaired (according to Mines Minister Iangalio as reported in the South East Asia Mining Newsletter 10 Sept 1993, p. 5). The mining will continue for at least another fifteen years and over a billion tonnes of sludge will be dumped.

The environmental damage is large, almost certainly irreversible and largely unpredictable. The ecology of the Fly River system has been changed by the sediment, and if claims that the river system is now biologically dead are exaggerated, the future effect of the dumping is largely unknown. There has been no independent environmental monitoring of the environmental damage. The only assessment is done by consultants paid by the mining company. It is known, however, that fish have vanished from some parts of the Ok Tedi, that the area of rain forest dying from the sediment will extend much further along the river flood plains as mining continues and that the bed of the river has been raised by more than a metre of contaminated silt over seven years.

In 1984 the mining company (Ok Tedi Mining Ltd) tried to build a tailings dam to contain the sludge but the dam collapsed in the course of construction and the company gave up the effort. BHP claims that a tailings dam is impossible to build in the geologically unstable terrain with an annual rainfall of up to 10 metres. Moreover an unsafe dam would of course pose the threat of catastrophic flood to the 30,000 downstream villagers. But there is no doubt that the villagers have already suffered. Their river-bank gardens have been destroyed, fishing has become impossible and the wild boar they used to hunt have disappeared.

The project has enormous significance for the Papua New Guinea economy. The nation was the sixteenth most indebted in the world in 1991. The debt stood at 130 per cen...