- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How We Write is an accessible guide to the entire writing process, from forming ideas to formatting text. Combining new explanations of creativity with insights into writing as design, it offers a full account of the mental, physical and social aspects of writing. How We Write explores: how children learn to write the importance of reflective thinking processes of planning, composing and revising visual design of text cultural influences on writing global hypertext and the future of collaborative and on-line writing. By referring to a wealth of examples from writers such as Umberto Eco, Terry Pratchett and Ian Fleming, How We Write ultimately teaches us how to control and extend our own writing abilities. How We Write will be of value to students and teachers of language and psychology, professional and aspiring writers, and anyone interested in this familiar yet complex activity.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Writing in the head

Chapter 1

The nature of writing

The aim of this book is to answer the question ‘How do we write?’ Writing is a peculiar activity, both easy and difficult. The more you think about how you do it, the more difficult it becomes. Everyday writing tasks, such as composing a shopping list or jotting down a reminder seem to be quite straightforward. You have an idea, you express it as a series of words and you write them down on a piece of paper. It is a natural and effortless process.

Yet we celebrate great writers as national heroes. Shakespeare, Eliot, Austen, Rousseau, Tolstoy, Joyce, Steinbeck, Sartre—they too expressed ideas as words on paper, but somehow they managed to transcend the everyday world and produce works of great insight, elegance and power.

There seems to be an unbridgeable gulf between everyday scribbling and great creative writing. It is not only a matter of having original ideas, though that certainly helps, but of being able to express them in just the right way, to communicate clearly or to excite passion.

Asking authors and poets how they work just widens the gulf. The descriptions you find in books of quotations seem to delight in separating creative writing from the everyday world. Thus, great writing is ‘the harmonious unison of man with nature’ (Thomas Carlyle), ‘the exquisite expression of exquisite impressions’ (Joseph Roux) or even ‘the achievement of the synthesis of hyacinths and biscuits’ (Carl Sandberg).1

Even The Elements of Style, for many years the handbook of writers and the arbiter of good prose style, has no explanation of the writing process, just questions and mysteries:

Who can confidently say what ignites a certain combination of words, causing them to explode in the mind?…These are high mysteries…. There is no satisfactory explanation of style, no infallible guide to good writing, no assurance that a person who thinks clearly will be able to write clearly, no key that will unlock the door.2

With advice like that, it is no wonder that many would-be creative writers give up after the first few attempts and stick to shopping lists.

Alternatively, we can look inwards and try to analyse our own writing processes. There is no doubt that words well up from somewhere within ourselves and that we can mull them over in our minds, selecting some, rejecting others, before expressing them on paper. But the mental activities that cause particular words to appear in the mind, that allow words to flow smoothly on to paper one moment and then dry up the next, are hidden below consciousness.

So, lacking a coherent account of the writing process, we lapse into metaphors or rules learned at school. I have already called on the familiar hydraulic metaphor in the previous paragraph, through phrases such as ‘well up’, ‘express’, ‘flow’, ‘dry up’. Other metaphors for writing include pyrotechnics (‘burning with ideas’, ‘fired the imagination’), exploration (‘searching for ideas’, ‘finding the right phrase’) and bodily functions (‘inspire’, ‘writer’s block?’). Sigmund Freud, as you might expect, had the last word on metaphors for writing. He argued that since ‘writing entails making liquid flow out of a tube on to a piece of white paper’, it sometimes ‘assumes the significance of copulation’.3

There is nothing wrong with metaphors (I shall be relying on them at various points in this book) so long as they are enabling. But a metaphor can too easily become a substitute for understanding. If we were to accept the hydraulic metaphor then we should need to look for ways to ‘turn on the flow’ when ideas ‘dry up’ or to ‘mop up the overspill’ of words that ‘gush out’ from the ‘wellspring of the imagination’. We would soon be so immersed in the metaphor that we could only think through it. Metaphors should be adopted with care, so that they assist in describing writing, but do not act as a barrier to new ways of thinking.

What of the rules for good writing taught at school? The ones I learned have helped me through some tricky moments. They are an odd bunch of edicts: ‘a story should have a beginning, a middle and an end’, ‘put each new idea into a paragraph’, ‘start each paragraph with a reference back to the preceding one’, ‘don’t end a sentence with a preposition’, ‘make a plan before you write’, ‘think about your reader’. Most rules for writing are grounded in common sense and good practice. They can be good companions, always at hand to offer advice when in need, but they don’t constitute an explanation of writing, nor a means to understand or develop your own writing abilities. And like most rules of everyday living, they are most useful when learned and then selectively ignored.

This was the extent of our understanding when I first became interested in how to write during the 1970s. There were numerous rules of grammar and style to be learned, a few general principles, some pervading metaphors and many unanswered questions.

Over the past 20 years these questions have begun to be answered and we now have a surprisingly full and consistent account of how people write. It began with the pioneering work of John Hayes and Linda Flower who studied writing as a problem-solving process.4 They adopted the simple but revealing approach of asking writers to speak aloud while writing, to describe what they were thinking. Through a painstaking analysis of these ‘think aloud protocols’ they built up a model of the writing process that has inspired a generation of writing researchers. An important contribution of Hayes and Flower was to study writing as it happens.

During the 1980s researchers found new ways to investigate the processes of writing, through analyses of pauses, directed recall (where writers are probed about a writing assignment they have just completed) and collaborative assignments where the writers are observed as they work together. They have built up an account of how we write that describes in detail the main component processes of writing: planning, idea and text generation and revision. This can explain how writers adopt different strategies according to their inclinations and needs. It offers a plausible explanation for problems such as writer’s block. And it provides valuable help for teachers and students of writing. The model of writing as problem solving is one important foundation of this book.

But for all its successes, writing as problem solving is just another metaphor. It has borrowed from the language of cognitive psychology, so that some writing researchers talk not about ‘exquisite impressions’ and ‘innermost feeling’, but about the ‘central executive’, ‘goals’ and ‘memory probes’. They show diagrams of the writing process in terms of arrows shunting information between boxes marked ‘long-term memory’, ‘working memory’, ‘cognitive processes’ and ‘motivation/ affect’. This has the effect of depersonalising the writing process, of making it appear as a self-contained mechanism, within but separate to the person who performs it.

More recently, writing has been analysed as a social and cultural activity. A writer is a member of a community of practice, sharing ideas and techniques with other writers. How we write is shaped by the world in which we live, with cultural differences affecting not just the language we use but also the assumptions we have about how the written text will be understood and used. The study of writing is itself influenced by culture, with some researchers concentrating on the teaching of writing within a multi-cultural society and others concerned more with writing as a professional and business activity.

This book does not reject these models of writing, but aims to incorporate them into a general account, by considering the writer as a creative thinker and a designer of text within a world of social influences and cultural differences. It attempts to resolve some of the paradoxes that face us when we try to understand how we write, such as:

- writing is a demanding mental activity, yet some people appear to write without great effort;

- most writing involves deliberate planning, but it also makes use of chance discovery;

- writing is analytic, requiring evaluation and problem solving, yet it is also a synthetic, productive process;

- a writer needs to work within the constraints of grammar, style and topic, but creative writing involves the breaking of constraint;

- writing is primarily a mental activity, but it relies on physical tools and resources from pens and paper to word processors;

- writing is a solitary task, but a writer is immersed in a world of social and cultural influences.

The book is organised around an account of writing as creative design which I shall sketch out in brief here.

An episode of writing starts not with a single idea or intention, but with a set of external and internal constraints. These are some combination of a given task or assignment (such as the title for a college essay), a collection of resources (for example tables of data about a company’s performance that need to be pulled together into a business report), the physical and social setting in which the writer is working (such as in front of a word processor in a newspaper office, or holding a pen and staring at a blank sheet of paper in a classroom), and aspects of the writer’s knowledge and experience including knowledge of language and of the writing topic.

Writing is, necessarily, constrained. Without constraint there can be no language or structure, just randomness. So, constraints should not be seen as restrictions on writing, but as means of focusing the writer’s attention and channelling mental resources. They are not deterministic, dictating thought in the way that the terrain dictates the path of a ball rolling downhill, nor are they like the rules of writing I listed earlier, guidelines to be picked up or discarded at will. Rather, they are the products of learning, experience and environment working in concert to frame the activity of writing. Constraints on writing can be modified, but to change them a writer needs to understand how they operate, and one skill of a writer lies in applying constraint appropriately. The notion of ‘writing as constraint satisfaction’ is one of the key themes of the book.

Because an episode of writing begins with a set of constraints rather than a single goal or idea, there is no single starting point. The point when a teacher hands out an assignment to a student might seem to be the obvious start for classroom writing, but it just adds one more constraint. The student may already have been collecting notes and attending classes that form the resources for the writing episode. Similarly, a poet or novelist may spend many months incubating ideas, taking notes and doing research, before starting a recognisable draft. Preparing mentally and physically are normally called pre-writing activities, but they all form an essential part of the writing process.

Constraints act as the tacit knowledge that prompts a writer into selecting a particular word or phrase. As we draft out a text we have no conscious control over the flow of words. The act of transcribing ideas into words ties up mental resources, so that we think with the writing while we are performing it, but we cannot think about the writing (or about anything else) until we pause.

A simple experiment will confirm this. Try to write an easy piece of prose (such as ‘what I have done since I woke up this morning’) and at the same time recite the nine times table. You will find yourself alternating between writing and reciting; it is not possible to do both at once. Nor is it possible simultaneously to write and think about the text’s structure. The only conscious action you can perform while producing text (apart from speaking it aloud) is to stop. If follows, therefore, that a writer in the act has two options: to be carried along by the flow of words, perhaps in some unplanned direction, or to alternate between reflection and writing. Most writers are unable to sustain prolonged creative text production (although, as we shall see later, it appears that a few prolific writers can do so), and so, in the words of Frank Smith,5 when we write we ‘weave in and out of awareness’.

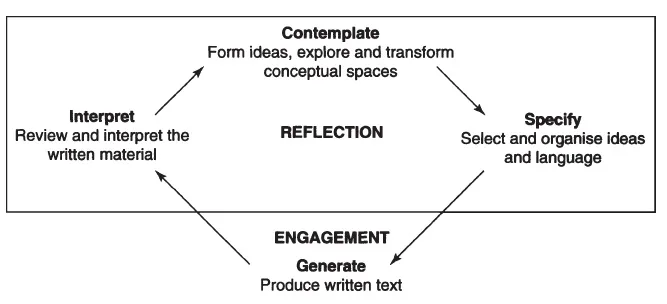

Figure 1.1 shows the cycle of engagement and reflection that forms the cognitive engine of writing. An engaged writer is devoting full mental resources to transforming a chain of associated ideas into written text. At some point the writer will stop and bring the current state of the task into conscious attention, as a mental representation to be explored and transformed.

Figure 1.1 The cycle of engagement and reflection in writing

Often this transition comes about because of a breakdown in the flow of ideas into words. It might be due to some outside interruption, a noise or reaching the end of a sheet of paper, or it might be because the mental process falters: the ideas fail to materialise or the words stop in mid-sentence. The result is a period of reflection.

Reflection is an amalgam of mental processes that interact with engaged writing to form the essential activity of composing text. It consists of ‘sitting back’ and reviewing all or part of the written material, conjuring up memories, forming and transforming ideas, and specifying what new material to create and how to organise it.

At the most general level, the differences between individual writers can be described in terms of where the writer chooses to begin the cycle of engagement and reflection (whether the writer starts with a period of reflection and planning, or with a session of engaged writing) and how it progresses. Each of the core activities—contemplate, specify, generate, interpret—can be carried out in different ways and writers can learn techniques (such as brainstorming and freewriting) to support and extend them.

This is a rather mechanistic account of the writing process. It doesn’t capture that agony of waiting for words that refuse to flow, or the delight of conjuring up an unexpected, novel idea. My account of the writing process needs to address the ways by which we create original meaning. How can we summon up a novel idea while writing, seemingly out of nowhere? How does a writer generate original phrases to express well-worn concepts? How have great writers been able to turn a broad topic (such as ‘pride and prejudice’ or ‘the origin of species’) into a creative masterpiece?

Fortunately, there is no need to develop a separate theory of creativity in writing. There is much overlap between creativity as part of writing and creative thinking in other areas such as science or music. The underlying mechanisms of creativity— such as daydreaming, forming analogies, mapping and transforming concepts and finding primary generators (key ideas that can drive a generative act)—do not rely on language (although they may involve it) nor are they unique to writing. There have been some recent, and convincing, attempts to explain creativity in psychological terms. Chapter Three shows how these can be applied to creative writing.

For much everyday writing, the account I have sketched out so far is sufficient (though far from complete as yet). A writer generates ideas, creates plans, drafts a text and reviews the work, in a cycle of engagement and reflection. But texts longer than a couple of paragraphs generally conform to an overall structure, a macrostructure, that frames the style and content of the text and organises the expectations of the reader. In general, we expect a novel to establish a scene, introduce characters, pose and resolve problems and reach a resolution. A typica...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part One Writing in the Head

- Part Two Writing with the Page

- Part Three Writing in the World

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access How We Write by Mike Sharples in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.