![]() PART I

PART I

Overview![]()

CHAPTER 1

Bringing Emotional Labor into Focus

A Review and Integration of Three Research Lenses

ALICIA A. GRANDEY • JAMES M. DIEFENDORFF • DEBORAH E. RUPP

I have to have a smile on my face. Some mornings that’s a little difficult … You’re concentrating on what you’re doing. It’s a little difficult to have that smile all the time. I have one particular girl who says to me,‘What? No smile this morning?’ So I smile. Clerks are really underpaid people.

(A hotel clerk, Terkel, 1972, p. 247)

Approximately 30 years ago, sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild (1979) published an article on emotion management in work and family roles, followed by her groundbreaking book in 1983: The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. In this work she proposed that the rise of the service sector was creating a new form of labor – emotional labor (EL) – where the worker manages feelings and expressions to help the organization profit. Such labor is illustrated in the quote above, from Studs Terkel’s (1972) acclaimed book, Working. What is clear from Hochschild’s book, and the above quote, is that a personal and enjoyable behavior – a smile – can also be a product available for public consumption in exchange for a wage.

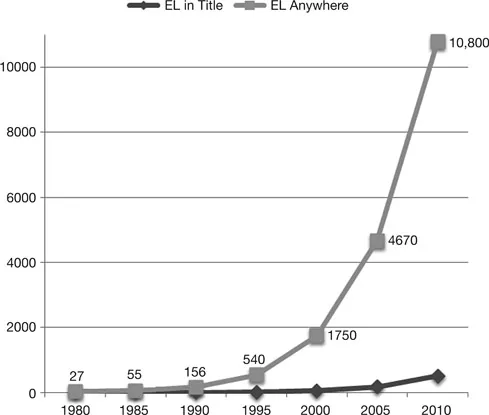

Hochschild’s (1983) naming of this form of labor sparked several lines of research over the last three decades. In fact, close to 10,000 articles have referred to EL; notably, over half of those articles were published since 2006, showing exponential growth in the attention to this concept (see Figure 1.1). In the broader context, EL is part of the growth of attention to emotions in sociology (Thoits, 2004; Wharton, 2009), psychology (Gross, 1998b), and the “affective revolution” in organizational behavior (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1995; Ashkanasy, Härtel, & Daus, 2002; Barsade, Brief, & Spataro, 2003). In sociology and organizational behavior (OB) particularly, the interest in EL is linked to the growth of the service sector worldwide (see www.cia.gov, The World Factbook), and more attention to interpersonal job demands (e.g., teams, client contact) (Humphrey, Nahrgang, & Morgeson, 2007). Though the service sector is often the focus of EL research (e.g., health care provider, teacher, paralegal, call center worker, fast-food cashier), many researchers consider EL to be a central component of any job requiring interpersonal contact (Diefendorff, Richard, & Croyle, 2006; Sloan, 2004). Thus, the ideas of EL can be applied to a majority of the current workforce.

Figure 1.1 Growth of published academic research on “emotional labor/labour”.

With three decades of study, we consider the time to be right to take stock of the emotional labor field by gathering the perspectives of experts from a variety of disciplines and theoretical orientations. The chapters of this book are intended to recognize the diverse research perspectives of EL (e.g., psychology, sociology, management, marketing) and the different ways of conceptualizing and investigating EL (e.g., event/episode, individual, group, organization, culture). These chapters review past research and identify key issues for future work to consider. The chapters outline methodological, theoretical, and practical issues in the literature as well as asking new questions in each of these areas. For example: How do personal abilities versus interpersonal power influence the way emotions are managed at work (Part 1)? How does physically proximal versus technology-mediated service differ in the management and performance of emotions (Part 2)? How does the global service economy – and the culturally diverse interactions that occur – change the experience of EL (Part 3)?

As a starting point, this introductory chapter focuses on defining EL. As the concept of EL has become more popular, its definition has broadened and the boundaries between the construct and other related constructs have become blurred. So, we start by asking the question:What exactly is EL, or perhaps more importantly, what is it not? In the present chapter, we review the conceptual development and measurement of EL over time and then propose a framework aimed at differentiating the concept of EL from other related concepts. We hope that some consensus can be reached regarding the definition and conceptualization of EL and that an agenda for future research on this increasingly relevant and important topic can be developed.

EMOTIONAL LABOR CONCEPT: THREE FOCAL LENSES

The answer to the question “what is EL?” is more complex than it may seem. We propose that there are three main “lenses” or perspectives that researchers use to “see” EL, but that using all three will result in the clearest vision. In Table 1.1, we compare the definitions, measurement, and outcomes of the three lenses: EL as Occupational Requirements, EL as Emotional Displays, and EL as Intrapsychic Processes. Though all three were originally part of Hochschild’s (1983) original conceptualization, different lenses tended to be used by different disciplines. The lens of EL as Occupational Requirements tends to be the focus in sociology (e.g., Lively & Powell, 2006; Wharton, 1993); the lens of EL as Emotional Displays tends to be the focus in organizational behavior (e.g., Ashforth & Humphrey, 1993; Rafaeli & Sutton, 1987), and EL as Intrapsychic

TABLE 1.1 Viewing Emotional Labor (EL] Through Three Focal Lenses

| EL as Occupational Requirements | EL as Emotional Displays | EL as Intrapsychic Processes |

|

| EL Definition | Jobs that require managing feelings to create an emotional display in exchange for a wage | Expressions of work role-specified emotions that may or may not require conscious effort | Effortfully managing one’s emotions when interacting with others at work |

| Key Publications | Hochschild (1979, 1983) | Rafaeli & Sutton (1987, 1989) | Morris & Feldman (1996) |

| Wharton (1993) | Ashforth & Humphrey (1993) | Zerbe (2000) |

| | Grandey (2000) |

| Central Concepts | Emotion work or management = done in private for personal motives | Emotional harmony = feelings, displays and emotional expectations are congruent (i.e., “affective delivery”) | Surface acting = way of modifying expressions to meet job expectations (i.e., suppress, fake) |

| EL Jobs = frequent interactions with public, must induce feelings in others, and management controls emotion | Emotional deviance = expressions are incongruent with expectations (i.e., “breaking character”) | Deep acting = way of modifying feelings to meet job expectations (i.e., refocus, reappraise) |

| Feeling/Display Rules = norms for how one should feel/display with others | Authenticity = extent to which expressions appear to be genuine | Emotional dissonance = state of tension when there is a discrepancy between feelings and displays |

| Measurement Approach | Qualitative (interviews, observation); O*Net | Observer ratings of expressive behavior | Actor’s self-reports |

| Proposed Outcomes | EL is functional for the organization but dysfunctional for the employee | EL is functional for organization and employee; only dysfunctional if highly effortful and inauthentic | EL as deep acting is functional to organization and employee; surface acting and dissonance are dysfunctional |

Processes tends to be the focus in psychology (e.g., Grandey, 2000; Morris & Feldman, 1996). These disciplinary roots explain why the lenses are often used separately rather than in combination, and contribute to the blurring of the EL concept. Our goal is to make transparent the assumptions of these lenses, so that future researchers can see EL more clearly.

Focal Lens #1: Emotional Labor as Occupational Requirements

In the first focal lens, EL is a type of occupation, a parallel concept to physical labor or cognitive labor. Hochschild (1983) suggested that the shift toward services, rather than goods, created jobs that required the task of pleasing customers to turn a profit. EL was proposed to be distinct from emotion management (i.e., emotion regulation, emotion work), which was performed in a private context for personal use. In viewing EL through this lens, certain jobs require EL and others (i.e., those lacking frequent customer interaction) do not.

Focal Definition and Measurement

The central tenet of EL within this perspective was that it occurred in jobs requiring the managing of emotions in exchange for a wage. High EL jobs were defined by Hochschild (1983) as having three characteristics: 1) frequent interactions with the public (i.e., customers), 2) the expectation of inducing emotions in others, and 3) the management or control of these emotional interactions. Jobs with all three characteristics are clearly EL jobs, though others may be argued to be EL jobs if they have one or two of these characteristics (see Table 1.2). Based on this definition, Hochschild (1983) provided a list of “high EL jobs” in the appendix of her book, which she acknowledged was “no more than a sketch, a suggestion of a pattern that deserves to be examined more closely” (p. 234). Caring work (i.e., nurses), professional services (i.e., paralegals), and enforcement services (i.e., bill collector, police) have all been studied as EL jobs but do not have the same level of the three characteristics (Thoits, 2004; Wharton, 2009).

With its roots in sociology, qualitative research approaches are often used to provide rich descriptions of specific job contexts and employee experiences within this domain. Hochschild (1983) conducted observations and interviews with flight attendants and bill collectors, illustrating the variety of emotion expectations (i.e., warmth and calm versus anger and intimidation), and identifying how management socialized emotional norms. Sociologists have conducted in-depth observational studies of emotional labor in prototypical low-status jobs such as fast-food server and cashier (Leidner, 1993; Tolich, 1993) as well as professional jobs such as police detective and paralegal (Lively, 2000; Stenross & Kleinman, 1989).

Focal Concepts

The qualitative approaches used in conjunction with this lens have yielded key EL concepts. Hochschild (1983) found that people working in EL occupations are socialized into certain feeling rules, or norms about how employees “should” feel when interacting with customers, clients, and patients. Others began to focus on display rules, or the expressive requirements of the job (Thoits, 2004). Wharton and Erickson (1993) reviewed three types of display rules: 1) Integrative display rules: the requirement to show positive emotions (e.g., liking, empathy) that “bind groups together” (p. 463); 2) Differentiating display rules: the requirement to show negative emotions (e.g., hostility, contempt) to create differences between others; and 3) Masking display rules: the requirement to show neutral emotions (e.g., calm) to convey impartiality and authority.

Status and gender were also central concepts within this perspective. The basic assumption of Hochschild’s (1983) work was that there is an imbalance of power in EL jobs with higher power (and often male) customers being able to act more freely on their feelings than lower power (and often female) employees (Hochschild, 1983; Thoits, 2004). As a result, employees in EL jobs were found to experience a loss of personal control resulting in self-alienation, emotional estrangement, and a host of social- and health-related problems. This may be particularly problematic in contexts with integrative (or deferential) display rules which also tend to be lower status and female-gendered jobs (Thoits, 2004). Occupations with differentiating (bill collectors, drill sergeants; Sutton, 1991) or masking (surgeons, police; Stenross & Kleinman, 1989) display rules tend to be more male-dominated and higher status.

Emotional display rules have been commonly studied as individuals’ perceptions of job requirements with customers (Diefendorff & Richard, 2003; Gosserand & Diefendorff, 2005; Schaubroeck & Jones, 2000) and other interaction partners (Diefendorff & Greguras, 2009; Sloan, 2004; Tschan, Rochat, & Zapf, 2005), permitting quantitative comparisons of EL requirements across jobs (e.g., Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Lively & Powell, 2006). This approach captures variation in the EL required of jobs, rather than categorizing jobs dichotomously as EL or not. In recent years, research has operationalized display rules as a) manipulated job requirements (Goldberg & Grandey, 2007; Trougakos, Jackson, & Beal, 2011), b) shared in work units (Diefendorff, Erickson, Grandey, & Dahling, 2011); and c) expert-coded descriptions of emotional demands by job title (Glomb, Kammeyer-Mueller, & Rotundo, 2004).

Focal Outcomes and Evidence

A key assumption of this lens is that requiring emotions in exchange for a wage is uniquely distressing to employees. This is examined in two broad ways: 1) comparing outcomes for employees in high-EL and low-EL occupations, and 2) comparing financial motives versus other motives for performing emotion work.

Hochschild stated that “emotional labor is sold for a wage … I use the synonymous terms emotion work or emotion management to refer to these same acts done in a private context” (p. 7). She recognize...