- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Action Analysis for Animators

About this book

Action Analysis is one of the fundamental princples of animation that underpins all types of animation: 2d, 3d, computer animation, stop motion, etc. This is a fundamental skill that all animators need to create polished, believable animation. An example of Action Analysis would be Shrek's swagger in the film, Shrek. The animators clearly understood (through action analysis) the type of walk achieved by a large and heavy individual (the real) and then applied their observations to the animated character of an ogre (the fantastic). It is action analysis that enabled the animation team to visually translate a real life situation into an ogre's walk, achieving such fantastic results.

Key animation skills are demonstrated with in-depth illustrations, photographs and live action footage filmed with high speed cameras. Detailed Case Studies, practical assignments and industry interviews ground action analysis methodology with real life examples. Action Analysis for Animators is a essential guide for students, amateurs and professionals.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Study of Motion

Asking Ourselves Some Key Questions

Let’s begin by asking ourselves a few questions regarding the study of motion.

We should start with the question, Why should animators undertake the study of motion?

It would seem perfectly feasible to argue that animators can produce work of a good standard and that is more than acceptable for all manner of productions without the need for such study. There are plenty of examples of self-taught artists who have gone on to become masters of their craft, not only leading the way for others to follow but creating seismic shifts in art and design and in the process becoming towering figures of genius within art history. Such remarkable individuals should be celebrated for their contributions and be seen for what they are: remarkable.

But such people are in the minority. The vast majority of people who work as creative artists within various traditions developed their talents along more conventional roads, studying at schools, colleges, or universities; a few fortunate ones have had the opportunity to study in the studios of established practitioners.

During a lecture and screening given by Richard Williams, the animation director of Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), at the Bristol School of Animation at the University of the West of England, he spoke of how the old masters of animation influenced him in the development of his craft and how the study of movement had helped him better understand the nature of performance-based animation. Although he was not apprenticed to the likes of Ken Harris, Art Babbitt, Grim Natwick, or Milt Kahl, he did have the opportunity to work closely with them. He studied their methods and processes and took what they had learned and applied it to his own work. He also made a systematic study of human movement; in doing so, he made his own major contribution to the art form. The way I see it, if this level of study is good enough for Richard Williams, it is good enough for me and my own students.

The one thing that none of these great animators depended on was the use of simple tricks or formulas. Don’t get me wrong; tricks, tips, and dodges have their place and allow an animator to develop his or her animation skills to a certain degree. They will even allow a student to imitate the work of others. However, if this approach is taken as the sole way of learning and creating animation, it can only lead to students developing their craft by rote, creating little other than formulaic animation. Through in-depth study of the craft, serious students will be able to gain real understanding of the underpinning principles of timing and dynamics. Ultimately this study will allow them to create for themselves a path toward making performance-based animation with originality. Without a doubt, a good grounding in processes, techniques, and methodologies, coupled with intense study of an art form, will enable animation students to make progress toward their goals.

However, neither the tricks of the trade nor rigorous study are a substitute for talent. Talent is something we are all born with to different degrees. Although the potential we possess for anything from playing football or singing to animating varies from person to person, we all have some potential in all these areas. Our job is therefore to develop our talents to their full potential. Perhaps it is fortunate that we do not all have the same capacities, since there would then be no giants among us—no Picassos, no Mozarts, no Pelés, no Hemingways, and no Winsor McCays or Tex Averys.

I have often heard people claim that they can’t draw. They can, it’s just that they haven’t yet learned how to do it or haven’t developed their full potential for drawing. The same is true for animation. Of course, natural talent will take you so far, but through study, talent can be further developed through patience, practice, and the systematic application of what you have learned.

That brings us to the next question: How should an animator undertake the study of motion?

We need to establish from the outset that there is no one process that will provide animators with all the answers they need for the study of motion.

They must identify and then use the most appropriate methods for their particular needs. Often this will be simply referencing a text such as this one; occasionally it will involve other very specific processes.

Gaining an in-depth understanding of motion is clearly best done through actually making animation; this is experiential learning. As with most things in life, having a good instructor or mentor will ensure that you learn at a faster rate and at a deeper level. When I first began animating in the early 1980s, I had absolutely no idea what I was doing, and I knew it. The one thing I was sure of was that to progress within the industry, I had to learn my craft. Learning the principles of animation and the mechanics of the production process was difficult enough, but compared to learning the intricacies and subtleties of human movement, these things were a breeze. When it came to mastering performance and acting, I am still learning after 20-odd years. In this regard I firmly believe that we never stop learning.

I was lucky enough to study under two first-rate but little-known animators, Chris Fenna and Les Orton, within a studio environment. For the best part of two years I studied their drawings, their animation timings, and the way they handled dynamics, which gave me a great start in developing my own understanding. It also enlightened me to the fact that different animators are suited to different kinds of performance. This level of first-hand experience is invaluable to the trainee animator who wants to come to grips with the demands of animation and the importance of the study of motion.

A collection of reference material is absolutely vital to the animator who wants to develop her craft. These days there is so much material available to the serious student of motion and animation as to be a little confusing; books, DVDs, animation, live-action film, Web sites, and online learning material all have their parts to play. Much of this material was unavailable to me as a young animator, though there were some good texts. One of the very best was the classic Timing for Animation, by Harold Whitaker and John Halas. I couldn’t afford my own copy, so I made copies of nearly the entire book using the studio photocopier; then, with my first paycheck, I bought my own copy, which I still treasure and use to this day. Now there are plenty of texts that provide good insight into processes of animation, and the Focal Press catalogue provides perhaps the greatest range of texts on all manner of topics from major contributors.

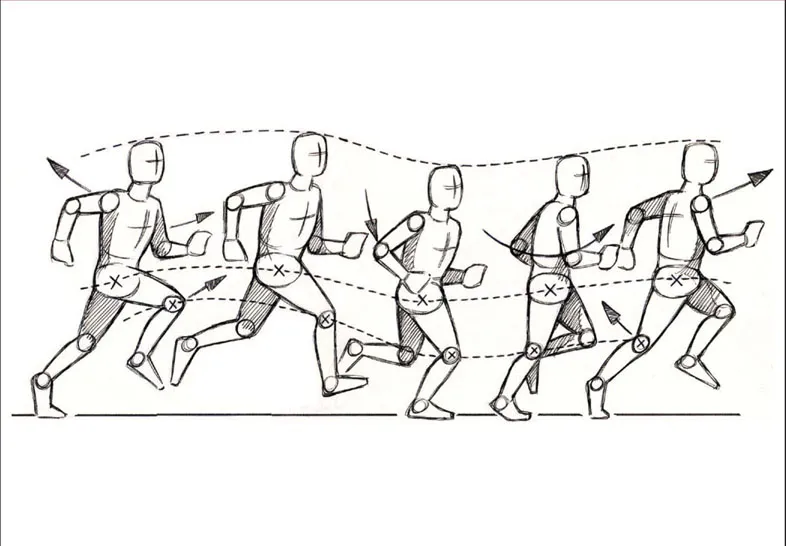

Watching and studying animation, not simply as a member of the audience being entertained but as part of your serious study of animation, will bring major rewards. You will find that going through parts of an animated sequence that is of interest to you a single frame at a time will help you analyze the movement. Begin by looking at the overall results in real time, then slowly focus your attention on the individual elements of the movement. Then, by single-framing the action, you will find that you gain a deeper insight into the separate actions and the way they interrelate. You will need to do this over and over again, checking each part of the motion in turn. This kind of analysis will enable you to gain insight into the way the master animators achieved those great performances. This idea is covered in more detail in the chapter on methodologies for analysis.

I began my own studies in action analysis by looking at the Disney classics Snow White, Bambi, and Pinocchio. I then moved on to studying the work of Tex Avery and Chuck Jones to gain an understanding of their particular brand of cartoon animation. Studying animated movement in this way does not necessarily help the student develop her directing skills or understanding of cinematography, but it does help a young animator in dealing with movement and timing.

As I began to study other animators, it became clear that all the great ones had their own distinctive approach to dynamics. Some concentrated on subtle actions; others had a broad approach to cartoon timing; some specialized in naturalistic animation. One only has to look at the differing approaches of Disney’s “nine old men” to appreciate these variations in approach. It is important for the student of animation to remember that the benefits of studying movement are not limited to the methods by which the animation has been made. Studying classical 2D animation is just as useful to those making computer graphics (CG) animation as it is for any other animator, as long as you remember that you are studying movement, not drawings. The important thing here is to choose only the very best examples of animation for your study.

Although it is interesting and rewarding to study the work of the great animators to achieve a deep understanding of motion, one often needs to go directly to the source: live action. Studying live-action footage of a range of subjects will provide the student of animation with a wealth of material to analyze. Studying the action of humans and animals first-hand is very informative, but this is not always practical nor possible. Animals cannot be expected to perform on cue, and there are some animals to which most of us do not have easy access. It is arguable whether it is better to study the action of humans and animals by direct observation or if video footage provides a better opportunity for more systematic study. Both approaches have their positive points. Rapid and complex movements are perhaps better understood by repeated viewing than live action offers. You can also freeze-frame video footage, but you can’t freeze frame live actions. The performance of live actors may also provide worthwhile reference, particularly if a distinctive dynamic action is sought. We may be familiar with the distinctive walks of both Charlie Chaplin and Groucho Marx and think that we have an understanding of the nature of these movements, but to accurately replicate such movements through animation, it would be as well to study the real thing. A wealth of wildlife documentaries is available to provide the animator with an excellent source for animal locomotion. There should be no need for the budding animator to visit the Arctic or keep a polar bear of his own in order to study them.

In the course of their work at some point or another, animators will probably find themselves dealing with two very distinct types of motion: naturalistic action and abstract action. Each of these types of motion presents its own range of possibilities and, as one might expect, its own particular difficulties.

For our purposes we can define naturalistic animation as any motion that is associated with realistic and recognizable movements, organic or nonorganic, undertaken in a completely believable manner. Although creating motion of this kind could present difficulties that are not easily overcome, at least identifying and studying the nature of movement is easy. Animators—and more important, audience members—are able to compare naturalistic animation against their own understanding of the real thing. Most of us know how horses run, how children walk, how the surface of water ripples in a breeze, and how smoke behaves; the list is almost endless. Because the audience can easily recognize the actual motion of each of these things, the demands placed on the animator are rather substantial; anything deviating from the audience’s first-hand experience will be instantly identifiable as erroneous and the suspension of disbelief will fail. The study of naturalistic movement for this kind of naturalistic animation may be a simple matter of accessing the appropriate research material, including, of course, first-hand experience.

Abstract motion, on the other hand, may be open to interpretation. This could provide some leeway in the animation because it can’t easily be measured against any “real” equivalent. Abstract motion may take on a wide range of actions, from cartoon characters designed in an abstract manner to actual abstract shapes. Subjects for this approach to animation could appear somewhere on a continuum ranging from the completely abstract movement of abstract shapes, movement that relates to nothing in nature, to movements more associated with cartoon animated motion. These may be recognizable inasmuch as they represent familiar things (cat, mouse, dog) though they do not move in ways that relate to that real-life thing.

At one end of that continuum we have the work of Oskar Fischinger, who specialized in abstract shapes interacting with one another and synchronized to sound. There is no motion within such work that we can measure against our own first-hand experience of these things. At the other end of the spectrum we have the work of animators such as Tex Avery, whose characters often fail to behave in the manner of the things they represent. However, as difficult as it may seem, animators working at either end of this continuum are able to make animation if not “believable,” then at least convincing.

Study of this type of abstract animation may be more problematic, though it is not impossible. Believability in this instance may be the attribution of such qualities as the weight attributed to an object. Momentum and inertia may still be applied to abstract animation, and in these cases the study of momentum and inertia in nonabstract forms may be of value. The manner in which birds fly or fish swim or the mechanical motion of machinery may provide adequate reference and a good starting point for creating abstract motion.

Then there are the types of actions that the animator might want to appear to be naturalistic, even though by their nature they are abstract or at least completely unknown. Take, for example, the animation of dinosaurs or dragons. Although the first type of creature did actually exist on earth, we are left with no first-hand account of their movements, even though we can glean a good deal of information about the way they probably moved by examining what does remain of them. The second example, the dragon, is completely fictitious; as such the study of dragons becomes difficult. However, we are able to apply what we have learned from other sources. The study of large land animals such as elephants, rhinoceros, and hippopotamus may help with both examples; the study of snakes may assist the animator in getting to grips with the animation of a dragon’s tail.

Early in my career I learned the value of using my own body to study and analyze action. I had to animate a number of rather difficult characters to a standard I had not previously worked to. This task was far more challenging than anything I had experienced before, and I was struggling. Then, on the advice of the project’s director, I began to act out the scenes for myself, not as myself but in a way that my characters would move. Ideally I would have used direct reference material, but this was not practical, so I used the next best thing: myself. I spent the next few weeks walking around the studio in both the aspect of a young, powerful, and power-crazed princess and as one of her short and very overweight courtiers. Believe me, this activity helped a great deal. I not only learned through direct visual observation of my own movements as seen in a full-length mirror, but I was able to feel how my body moves in a particular way when undertaking a specific action. This exercise gave me insight into where the weight in my body was at any particular moment, where the center of gravity was, and how the figure balanced, and I was able to locate all the stresses and tensions within my muscles.

Years later some of my graduate students, who were then working for a studio in London making CG animation involving dinosaurs, were doing exactly the same thing as they too struggled with the animation of creatures they had no direct reference for. To get a better idea of how a wounded pterodactyl might have hobbled across a Jurassic beach, they took to hauling themselves along using crutches as makeshift wings and filmed the results. This technique worked very well, and the animation was very successful.

As a young animator I had far less technology at my disposal for creating my own reference material. Motion capture, digital photography (including stills), and video capabilities in mobile phones were not available to animators in the 1980s the way they are today. These are wonderful tools that can be used to great effect as long as they are used appropriately. Animators should not depend on any single source of referencing but rather should use a range of resources: textbooks, film (animation and live action), photography (your own and that of others), first-hand animation material (observation and sketchbook work), the first-hand experience of others through mentorship (one of the most useful techniques), and motion capture. We will look in more detail into each of these approaches later in the text.

The next question we should then ask is, Who are the practitioners for whom such a study is relevant?

All artists, designers, and creative individuals of various kinds take the study of their particular craft very seriously. This applies equally to those working within the creative industries and those engaged in more independent or less commercially oriented practices. Naturally, artists of all types deal with the particular aspects of their craft relevant to their art or creative process in their own way. In addition to a wide and varied range of practical and aesthetic issues, each artist will have an understanding of aspects particular to his or her craft: Painters will probably have a deep understanding of color theory; sculptors may have a profound understanding of form, space, and materials. Photographers have an understanding of light; musicians and composers have an understanding of the intricacies of sound; and graphic designers understand letterforms and typefaces, layout, and the relationship between text and image. In the same way, it is clear that animators need to study and gain an in-depth understanding of the nature of movement and dynamics. The pursuit of relevant knowledge through in-depth study, together with craft skills, underpins an artist’s creati...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Study of Motion

- Chapter 2 Dynamics and the Laws of Motion

- Chapter 3 Animation Principles

- Chapter 4 Animals in Motion

- Chapter 5 Figures in Motion

- Chapter 6 Action in Performance and Acting

- Chapter 7 Capturing and Analyzing Action

- Chapter 8 Research

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Action Analysis for Animators by Chris Webster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Digital Media. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.