- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Stone Tools & Society

About this book

Stone tools are the most durable and, in some cases, the only category of material evidence that students of prehistory have at their disposal. Exploring the changing character and context of stone tools in Neolithic and Bronze Age Britain, Mark Edmonds examines the varied ways in which these artefacts were caught up in the fabric of past social life. Key themes include:stone tool procurement and production * the nature of technological traditions * stone tools and social identity * the nature of exchange and the significance of depositional practices. As well as contributing to current debate about the interpretation of material culture, Dr. Edmonds uses the evidence of stone tools to reconsider some of the major horizons of change in later British prehistory.From the production of tools at spectacularly located quarries to their ceremonial burial or destruction at ritual monuments, this well-illustrated study demonstrates that our understanding of these varied and sometimes enigmatic artefacts requires a concern with their social, as well as their practical dimensions.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Squeezing blood from stones

Over four and a half thousand years ago in what is now south Dorset, someone took up a nodule of flint and began to work. He or she probably turned the lump of stone in the hand several times, familiarizing themselves with its weight and form, before raising a hammerstone and letting it fall to detach a flake.

With this first removal of flake from core, they continued to turn the stone, running their fingers across the dark, inner body of the flint and the coarse, off-white skin of the nodule. The platform or striking surface prepared, they began removing that outer cortex as the flakes sprang out like sparks from beneath the hammer. Now their fingers fastened onto ridges and scars as they casually trimmed the edges to create an angle for working. A dust like powdered glass coated their fingers, and small chips of flint joined the flakes and spalls that lay scattered on the ground around them.

Here they may have paused … bending to retrieve one of the larger flakes from the scatter that lay at their feet. Tracing its contours between finger and thumb, they may have considered the potentials it held before letting it fall a second time in favour of the parent stone and the task at hand. Gradually, the shifting tempo of hesitant working gave way to a more fluid rhythm as hand and eye relaxed to an accustomed edge. Carrying them forwards through the stone, the rhythm continued unbroken – the scatter on the ground slowly darkening as the last peninsula of cortex was removed. Even the slow rotation of the core kept time with the steady rise and fall of the hammer. Then, when it seemed as if they might have continued on until the stone in their hand had vanished, they paused and bent once more, placing the faceted core among the debris. Brushing the dust and splinters from their legs, they gathered up this loose assemblage and walked to where a small pit lay open, its mouth gaping in the freshly cut chalk. Leaning forward, they poured the stone through the open mouth until it came to a clattering rest amidst the shards of a broken vessel, the fleshy jaw of a pig, and the still warm ashes from a fire. As they pulled the dark soil in from the edges of the pit, the smell of the ashes faded as first the jaw, then the flint, disappeared from sight. Rising again, they scattered the remaining soil across the ground, and turned away from the darkened circle.

Anyone with any flint knapping experience will tell you how difficult it is to describe the interweaving of action and thought that marks the making of a stone tool. As with many of the tasks that we routinely perform today, the act of working around a piece of stone involves a tacit negotiation of the material, in which hands, eyes, ears and expectations are all engaged. Knowledge of how to proceed and the intentions of the producer are constantly tempered by the conditions encountered as the raw material is transformed from its original state to a specific cultural form. This process resists conscious articulation. Indeed, it often proceeds most smoothly when the gestures and procedures that make up the act remain partly unconsidered or taken for granted (fig. 1).

In attempting to study of the results of this process – assemblages of prehistoric tools and waste – archaeologists have available a battery of techniques. These techniques allow us to ‘read’ the scars and ridges on the surfaces of artefacts and by-products and to grasp some of the material dimensions of tool production and use. We can determine the physical, chemical and mechanical properties of different stones, assessing the constraints and potentials that they create. Through experiments and morphological analysis, we can estimate how much waste will be produced during the making of a tool or the working of a core (fig. 2). We can specify what forms the waste flakes will take and the relative frequencies in which they are likely to occur. In exceptional cases, we can even refit flakes to their parent cores, creating complex three-dimensional jigsaws which allow us to capture particular episodes of working in more detail (fig. 3). To this list can be added techniques linking particular raw materials with their geological sources, and those which reveal how, and on what material, different tools were used.

1 Although people could exercise a measure of choice, the manner in which different stones were worked and used in the past depended to a certain extent on their physical and mechanical characteristics. Materials such as flint and some volcanic rocks have a regular crystalline structure which allows them to be ‘flaked’ in a regular manner. Other materials such as granite possess a rather different structure. As a result, they can only be rendered into tools by the laborious process of pecking, grinding and polishing. Materials such as flint can be worked in a number of ways: by direct percussion with a stone, antler or wooden hammer; by indirect percussion using a hammer and a punch; and through the use of hammers and anvils. Flakes and core tools may also be ‘retouched’ through direct percussion or pressure flaking.

2 We can learn as much from the waste created during the making of tools as from the finished products. In the case of materials such as flint, the waste or ‘debitage’ created during tool production and use can be used to identify general ‘reduction sequences’ – the steps or procedures followed in transforming a lump of stone into a cultural artefact. Found in excavations or on the surfaces of ploughed fields, different classes of waste provide valuable information on the character and spatial organization of stoneworking.

Devoted as it is to the stone tools of Neolithic and Bronze Age Britain, this book would not be possible without these and other techniques. Indeed, the description of flintworking with which this chapter opened is itself derived from a refitting study. But as that passage also suggests, the issues that we face in dealing with these traces take us beyond questions of physical description. Certain techniques may allow us to reconstruct the material specifics of this act and to explore some of the choices that were made in the creation and working of the core. But they do not provide us with a basis for understanding the cultural milieu in which that act was undertaken, nor the purposes that were served by the deposition of the entire assemblage in the ground.

Like the routines that shape much of our lives today, the tasks undertaken by people in the past would have provided a frame through which they might have come to recognize aspects of their world and themselves. The tools and waste that we recover would have been entangled in that world of social practice, providing cues for this process of recognition and interpretation. As such, the ideas that shaped their production and use would have stretched beyond problems of procedure to encompass concepts of the self and society. With the passage of time, however, these artefacts have become disentangled, only to be caught up in new frames as we try to ‘make sense’ of them in the present.

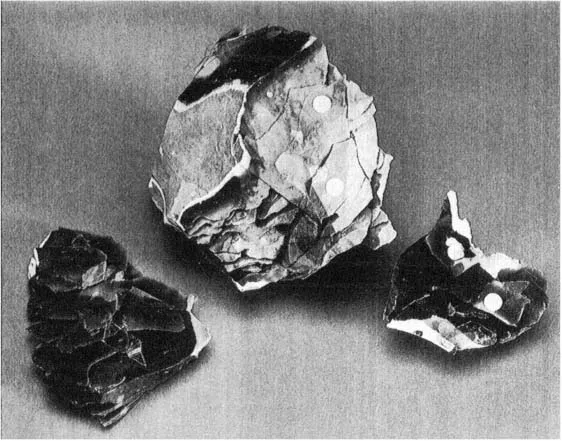

3 A refitted flint core. Occasionally, closer analysis of waste material makes it possible to identify the ‘grammar’ or pattern of choices that people followed during particular episodes of stoneworking. This is often explored in the context of refitting – the reassembly of flakes and spalls around the core or artefact from which they were struck.

These two themes of description and interpretation are also intertwined in archaeological practice, so that it is not always clear where one begins and the other ends. As the title suggests, this book documents some of the principal categories of stone tool that were made, used and discarded in later prehistoric Britain. But at the same time, it is also concerned with the conditions under which those artefacts were brought into being. In particular it highlights the ways in which the production, use and deposition of stone tools played a part in maintaining or reworking the concepts of identity and authority that were recognized by people in the past. The remainder of this chapter serves as an introduction to some of the problems that surround our attempts to squeeze blood from stones. This brief discussion provides the point of departure for the chapters which follow.

Approaches to prehistoric technology

For some time now, it has been accepted that the study of stone tools is synonymous with the study of technology. Commonly made and used in the execution of practical tasks, stone tools seem to sit comfortably within this general category, amenable to the forms of analysis and explanation favoured in technological studies. While its significance may have changed in keeping with broader shifts in our perspectives, the technological realm has long been granted a preeminent position in our accounts of the past. From the inception of the Three Age system through to more recent studies, it has often been cast in a major role: as a marker of cultures, as an indicator of evolutionary development and as a system that determines the character of society and stimulates change. Admittedly, we are now more reluctant to equate particular artefact types or assemblages with specific ‘cultures’, or with stages in grand evolutionary schemes. Moreover, we now acknowledge that while technologies and social relations are often inter-twined, there is little merit in the view that productive forces shape society in a strict and deterministic sense. Yet, at a practical level, much research continues to be guided by these long-standing assumptions regarding the significance of technology and the ‘effects’ that it has upon economic and social life.

In the study of stone tools, these assumptions are apparent in the priorities that are assigned to different avenues of research. More often than not, questions of function are given pride of place, as ever more detailed descriptions go hand in hand with general discussions of subsistence or ‘food-getting’ behaviour. Similar limits are often placed upon the treatment of the lithic scatters identified through fieldwalking and other forms of surface survey. For the most part, we tend to use these data to plot the location of settlements, taking these as reflections of broader economic regimes. These are obviously important questions to consider. Yet as new descriptive techniques are developed, or new applications are found for existing analyses, so it seems that the scale and scope of research becomes increasingly narrow and specialized. In short, we seem to leap from detailed descriptions of wear traces on tool edges to abstract models of subsistence and settlement that span vast tracts of space and time. Only rarely do we consider the problems that accompany movement between the two.

In a few cases, this emphasis upon description has been rejected in favour of more explicit proposals regarding the conditions that may have shaped tool production and use. These studies have generally been based upon perceived ‘regularities in technological behaviour’ which are held to apply at all times and places, and here it is the adaptive significance of technology which is stressed. Particular attention is often paid to the efficiency of tools in the performance of tasks, and to the scheduling of tool procurement and production in relation to the availability of different resources. Under such a rubric, patterns of tool production, use and discard are generally cast as responses – adaptations which allow for group survival in the face of particular sets of ecological or social circumstances. Insofar as they stress the need for an explicit theorization of lithic studies, such approaches remain useful as tools with which to explore the phenomena that we study. Yet it is still possible to question the vast scales on which analyses are conducted and the assumptions upon which they are often based. Here again, the emphasis remains upon the functional dimensions of particular tools and techniques and the effects they may have had upon productivity and social organization.

Despite profound changes in our concepts, aims and techniques, our approaches to stone tools have remained rooted in a long-established tradition of enquiry. In keeping with this tradition, the technological system is generally seen as an arena which is somehow divorced from history and from lived experience. It is a realm where decisions are taken on the basis of an explicit and utilitarian logic and in which responses are made to largely external stimuli. More often than not, prehistoric technology is viewed as ‘hardware’ – placed between people and nature – which allows for the more or less efficient exploitation of particular resources by human groups. In effect, it is held as an objective field of past social life which presents relatively few problems for the contemporary observer. All that we appear to require for a satisfactory interpretation is detailed description and ‘common sense’.

Of course it does not follow that the artefacts that we recover were not created and used in the execution of practical tasks. If functional analysis tells us nothing else, it does at least demonstrate that even unmodified pieces of stone could be employed for a wide variety of purposes. What is at issue is the belief that descriptions and ‘common sense’ are really all that are needed. Questions of function and productive efficiency may be important. But they do not provide a sufficient basis for capturing the broader roles that these objects may have played in past societies. This does not mean that our descriptive techniques are somehow flawed. They may have played their part in reaffirming a view of lithic technology as hardware, as much by their character as by their results, but they nevertheless remain vital. What needs to be reconsidered is the framework within which they are set.

Material culture and social reproduction

This need for reconsideration has been addressed in recent studies of past and present material culture. Many of these studies start from the idea that our location in western society has an inevitable impact on our views of the past and how it may be studied. Perhaps the most basic point to be made is that our contemporary circumstances encourage a view of objects which denies their position in webs of social and political relations. Given the extraordinary volume of commodities that circulate today, and our tendency to discuss things in quantitative terms, this argument remains persuasive. Indeed, the prevailing view of technology as hardware provides a good case in point. What we often overlook, however, are the roles played by everyday objects in shaping our understandings of self and society.

Some aspects of this role are more easily identified than others. For example, we generally have no difficulty in recognizing the importance of insignia, uniforms and badges of office as cues for the classification of people according to their positions or roles within society. Motifs and costumes often carry complex and even abstract ideas regarding the authority vested in particular people, or the qualities, beliefs and histories that separate them from others. What is sometimes more difficult to grasp is the rather more subtle part played by material culture in guiding our opinions and perceptions. Even a cursory glance at the totemic images produced by the advertising industry demonstrates the extent to which we endow many practical objects with ideas and values that extend far beyond their immediate utility. Just as these associations may influence our decisions as to what to buy, use or wear, so they also play a part in guiding our appreciation of other people. Visiting someone’s house, we make remarkably rapid and sophisticated assessments of the furnishings and trappings that we encounter in different areas. How are the rooms furnished? What objects or paintings are displayed? Is the kitchen equipped with the latest styles of knives and cooking pots? Where they are acknowledged at all, the rapid judgements that we make on the basis of these readings may be explained away as a matter of taste or preference. But they remain crucial to the ways in which we come to think about or categorize other people in terms of their economic and socio-cultural identity.

At the same time, the routine use of material items also provides a medium through which we come to know ourselves. As Winner states:

… individuals are actively involved in the daily creation and recreation, production and reproduction of the world in which they live. As they employ tools and techniques, work in social labour arrangements, make and consume products and adapt their behaviour to the material conditions they encounter in their natural and artificial environment, individuals realize possibilities for human existence.

Put simply, tools may not determine the character of society, but they are nonetheless caught up in the process by which the social order is continually brought into being. As such, they are also resources that can be drawn upon when people attempt to question or rework aspects of the conditions under which they live. In our own society, anthropologists and sociologists have shown how concepts of personal and group identity are often carried through the clothes that we wear, the tools that we use and the trappings that we surround ourselves with. Brought together in the repertoires and routines that make up our lives, material categories simultaneously contribute to the shaping of our identities at a variety of levels. Often passing almost unnoticed, they help us to classify ourselves as members of particular age or gender sets and as people who occupy particular positions within broader socio-economic and political structures. They may also signify aspects of our identity as members of particular cultural groups or even nation states.

Similar ideas may also be taken on board through the spatial pattern of our daily lives. For example, recent studies in cultural geography have shown how the spatial arrangement of the urban environment is informed by (and helps to reaffirm) many of the social, economic and political divisions that cross-cut society. At a more localized level, the spatial order of many day-to-day activities may also lend itself to the maintenance of a variety of social categories and norms. For example, parts of a house may have practical and historical associations with different categories of person. Some rooms may have stronger links with women than with men, and even the tools or utensils that we associate with different tasks may carry ideas about specific divisions of labour and authority. Although we seldom think about these associations and may even laugh when they are brought to our attention, the routines and paraphernalia of these tasks may still play a part in defining our sense of place within the home and within a broader social order.

Similar observations have been made in very different contexts. For example, Henrietta Moore has shown how the organization of many day-to-day activities among the Marakwet of Kenya is both an expression and an outcome of distinctions drawn on the basis of age, gender and kinship. The artefacts and materials that are caught up in those activities are imbued with ideas related to traditional links between particular tasks and specific categories of person. Equally, among the Loikop (Samburu), the production and use of spears is intimately bound up with ideas about the qualities and roles that constitute adult male identity. Through their production and use, these artefacts simultaneously stand for particular social categories and provide a medium through which those categories are realized. Indeed, it is t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface and acknowledgements

- 1 Squeezing Blood From Stones

- 2 Technologies of the Earlier Neolithic

- 3 Contexts for Production and Exchange in the Earlier Neolithic

- 4 Sermons in Stone: The Later Neolithic

- 5 Stone in the Age of Metal

- 6 The Place of Stone in Early Bronze Age Britain

- 7 The Erosion of Stone

- Glossary

- Further reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Stone Tools & Society by Mark Edmonds in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.