![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Events are based in society and involve people. They comprise interactions between people and places and they have costs and benefits. As such there is a need to understand the dynamics of the world in which events are situated and to which they contribute. We believe that this must go beyond the ‘how to’ tool-kit approach of a management degree, regardless of the importance of the practical skills such courses provide. The burgeoning of events management courses in the UK and the emerging profession of events management globally in recent years (Harris and Huyskens 2001) responds to the increasing number of ‘events’ in society at large (see for example Boissevain 1992, 2008; Guiu 2008; Kooistra 2011; Gibson and Connell 2011). However, the study of events is nothing new as many disciplines and other fields of studies have used event contexts to gain a deeper understanding of their own area. For example, the field of tourism has long focused on the role of events in attracting tourists by adding to the cultural offer of destinations. Indeed, the text by Greenwood (1989) is based around an examination of the Alarde festival in the Basque region of Spain. Although Greenwood's central discussion on the development of a local festival into a tourist attraction has been subject to much debate in the field of tourism studies, his work, which illuminates the intersection between people, place, politics and commercial interests, is based in the context of a public event. In addition there is much academic literature on the subject of events to be found in the tourism studies journals, among other areas of study – see for example Getz (2007, 2012), who acknowledges that events are linked to not only specific areas of study, for instance performance studies, but also embedded in major academic disciplines including, for example, social anthropology, sociology and cultural geography.

The inspiration for this book came from both of our interactions with events management programmes at universities based in the UK. We have observed that events management students struggle not only with drawing links between the events and tourism sectors (and other related sectors) but also with the socio-cultural context of events. We both come from a social science based tourism studies background and we understand that many of the issues that underpin the management of anything need to be informed by insights on the social and cultural world found in the social sciences. We want to enrich the study of events and provide students with the opportunities to explore these aspects of their chosen area of study, and develop their critical and creative skills, which should underpin all aspects of university study for the betterment of society.

Our concern is the non-business aspects because often business elements have become over-privileged in the studies of events to date. We believe that one danger of a sole focus on managerial and business aspects of the studies of events is that it masks other areas of study relating to events, and often disregards events that cannot be planned, managed and exploited for economic purposes. As Jackson notes (2005: 1) ‘The course of history, like the course of any human life, comprises a succession of turbulent events interrupted by periods of comparative calm.’ There are occurrences in life that are unpredictable and can be life-changing, for example a car accident or violent attack. Such events do not fall under the remit of commercial-based sensibilities and, as such, the business focus of events appears to be concerned only with that which can be staged. Underpinning these orchestrated events is an unspoken ideology that perpetuates the need to manage, categorise and bureaucratise social interaction and influence social order. It appears to us that the main concern is with the commodification of existing rites and rituals and the development of economic enterprises.

The study of events

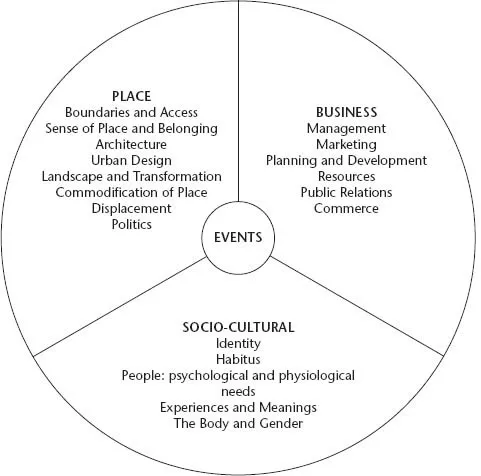

An event is a mix of elements that all overlap to inform event practices. Events happen at a specified place, they involve people of different socio-cultural backgrounds and incorporate elements of business practices (whether this might be a large-scale fundraising event or the organisation of a child's birthday party). Figure 1.1, demonstrates the links between the practice of events management and the socio-cultural and place elements that this book seeks to illuminate. All these aspects play a role in events and therefore studies of events should consider each of them. We believe that a comprehensive understanding of the nature of events can only be achieved by acknowledging all three features, which contribute to the making of an event regardless of its purpose.

In these opening paragraphs we have been using the word ‘events’ but in thinking through our approach to the studies of events for this book the word has perplexed us more and more and we have found ourselves challenging the meanings of the term. It is to this thorny issue that we now turn. If we look at dictionary definitions we find the following:

happen, occurrence, an incident, any one of the possible occurrences which happens under stated conditions, an item in a sports programme, that which

FIGURE 1.1 The main features of the studies of events

results from a course of proceedings, a consequence, what becomes of a person or thing (fate), to come to pass, to expose to the air. (Shorter Oxford English Dictionary [SOED])

From this we can gather that in fact anything can be understood to be an event, something that happens or occurs. Therefore it is no surprise that the word has been used within management culture to describe a disparate range of activities without any clear justification or real definition. Jago and Shaw (1998) draw attention to the confusion within the events literature around the segmentation of events. They list the transposability of synonyms connected to the terms ‘major event’ ‘special event’ and ‘hallmark event’ and highlight that ‘there is no consensus in the literature about the relationships between the various categories of events’ (Jago and Shaw 1998: 25). In our view, the attempts to put meaning in the categories through identification of attributes are by their very nature relative and based on prerequisites which are themselves open to interpretation. For example, McDonnell (2003) lists qualities, which make up a ‘special event’ (such as having a festive spirit, being unique, being authentic) but clearly states that a special event does not have to have all of these features to be considered a ‘special event’.

After all, an event is any act in the conduct of life. However, in terms of the increasing management culture associated with the advancement of a neoliberal political economy, in which the quantification and management of nearly all areas of the social world is a central project, it appears that all facets of social interaction and practice require a bureaucratic response and structure (Handelman 1998). This may be particularly so in the public arena, where groups of people united in a common cause may come together. Taking the UK as an example we have seen curbs in collective representation in all sorts of ways – from the eroding of trade union power to the restrictions on organised demonstrations.

THINK POINT

In the summer of 2011 in the UK there were a number of demonstrations or riots, which resulted in acts of civil disobedience including looting, arson and street battles with the police. Are these happenings an event and if so should they be part of your study at university?

Commonly used terminology found in the events literature such as ‘mega event’ and ‘hallmark event’ have developed with links to the contexts of globalisation, marketing and economics, and reflect the centrality of managerial approaches in studies of events. Conversely, the terms ‘spectacle’ ‘festivals’ ‘carnivals’ ‘ceremonies’ and ‘parades’ are rather applied to socio-cultural contexts within other areas of study and major academic disciplines. Thus, we would like to foreground the existing theoretical insights of the social sciences (e.g. ritual, consumption, ideas of performance) and (re-)introduce them into events management courses, and, as a result, encourage discussions and thinking about social science discourses in the studies of events, recognising that some of these issues are already being addressed in existing events curricula.

In other words, ‘events’ encompass all the occasions listed in Table 1.1, the study of which is deeply rooted in the socio sciences and can therefore provide firmer theoretical underpinnings for the complex dynamics that make up these things labelled ‘events’. We list these terms and their dictionary definitions (OED) as a starting point to broaden the research terminology in events management and not to rely on a single all-encompassing word. To be clear, we are using ‘events’ in this book as a term which covers spectacle, rituals, festivals, carnivals, ceremonies and parades but does not refer to the common categorisation found within the events management discourse.

In our experience, events management students often struggle to recognise the linkage between their chosen course and other areas of study and academic disciplines. Thus, having emphasised the complexities and difficulties of understanding what an event is, we further need to situate the study of events in the social sciences

TABLE 1.1 Broadening event terminology

| Terminology | Explanation |

| Spectacle | a visually striking performance or display; an event or scene regarded in terms of its visual impact |

| Ritual | a religious or solemn ceremony consisting of a series of actions performed according to a prescribed order1 |

| Festival | a day or period of celebration, typically for religious reasons; an organised series of concerts, plays or films, typically one held annually in the same place |

| Ceremony | a formal religious or public occasion, especially one celebrating a particular event, achievement or anniversary; the ritual observances and procedures required or performed at grand and formal occasions |

| Carnival | an annual festival, typically during the week before Lent in Roman Catholic countries, involving processions, music, dancing and the use of masquerade; inversion2 |

| Parade | a public procession, especially one celebrating a special day or event |

| Procession | a number of people or vehicles moving forward in an orderly fashion, especially as part of a ceremony |

| Celebration | the action of celebrating an important day or event |

Notes

1 A ritual does not need to be solemn; see our discussion in chapter 3.

2 A carnival can also encompass the suspension of social norms.

as this will help students to better appreciate and recognise how their programme of study is embedded in wider research programmes and agendas. In the preceding discussion we drew attention to some links between the study of tourism and the emergence of the study of events. In addition, we can note that these things we call events are related to other areas of study, themselves underpinned by social science approaches.

To bring the focus back to the purpose of this book, its key theme is that events take place within a socio-cultural context and events managers must be sensitive to social science theories and issues, which affect the industry. Further, those engaged on an academic route to the understanding of events also need to appreciate the theoretical lineage to which some discussions and critiques are indebted, to ensure the effectiveness of their own research and outputs. To this end we have identified areas that appear to us to be informative in terms of an introduction to a social science understanding of events. The rest of this chapter provides an outline of the structure of the book.

Chapter outlines

We start in chapter 2 by considering the social significance of events. To do this we first think about the term ‘society’ – what it means and the relationship of the individual to it. We introduce the terms ‘structure’ and ‘agency’ to illuminate the complex nature of the interplay between individuals (agents) and the whole, or structures that help to inform actions and dispositions. We then examine the evolutionary nature of society by looking at the different stages of societal development that have been identified. These stages are the pre-modern, modern and postmodern eras and connect their characteristics to the different forms that events take in each period. In particular we look at some of the key characteristics and processes associated with modernity that have influenced the development and practice of varying types of events. We note that the modern phase is characterised by an increasing number of events both in Europe (Boissevain 1992, 2008) and the United States. The chapter introduces the work of Durkheim (1933) and Tönnies (1957) to help us understand the changes in social conditions and practices as society moved from a pre-modern to a modern state.

In chapter 3 we focus on ritual and rites of passage, for example celebrations such as birthdays and religious ceremonies. Theories relating to the understanding of ritual are important areas of study in the social sciences, particularly in social anthropology. They help us to explore how individuals and/or social groups understand their identities. Many happenings that are incorporated under the terminology of events can be understood as rituals or rites of passage, so there is much to be learned about their practice by considering social science perspectives. The chapter introduces the work of Arnold van Gennep (1960) on rituals as rites of passage, discussing the role of rituals as markers of life stages. Many personal events fall into the category of a rite that signals change in, for example, status; a wedding for instance acknowledges the change from being single to being married. We go on to think about how Victor Turner (1969) developed van Gennep's ideas, identifying that all rites involve three distinct phases, which are the pre-liminal, liminal and post-liminal stages. We also examine the ritual narratives and objects linked to rites. Although the foundation for many of the theories is a concern with religious practices, the ideas are nonetheless still relevant for occasions not grounded in religion and we identify a number of secular rituals. The development of these secular rituals often relies on trying to ground the event in a sense of tradition which at times does not stand up to historical scrutiny. To understand this dynamic further we consider the idea of invented traditions.

In chapter 4 we move on to the importance of performance to understandings of event consumers, narratives and experiences. We explore the term ‘performance’ and demonstrate that events are composed of a number of different performances and actors, including the audience and the ‘players’. We also consider the event as a performance highlighting a series of steps that all events have in common. We introduce the work of Richard Schechner, who has written extensively on perform...