- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Sound Engineering Explained

About this book

This straightforward introduction to audio techniques guides the beginner through principles such as sound waves and basic acoustics and offers practical advice for using recording and reproduction equipment. Previously known as Audio Explained, this latest edition includes new material on: reverberation and its use in recording; principles of digital mixing; digital recording; including MiniDisc and MP3; digital artificial reverberation.

Designed with the student in mind, information is organised according to level of difficulty. An understanding of the basic principles is essential to anyone wishing to make successful recordings and so chapters are split into two parts: the first introducing the basic theories in a non-technical way; the second dealing with the subject in more depth. Key facts are clearly identified in separate boxes and further information for the more advanced reader is indicated in shaded boxes. In addition, questions are provided (with answers supplied at the end of the book) as a teaching and learning aid.

Sound Engineering Explained is ideal for both serious audio amateurs any student studying audio for the first time, in particular those preparing for Part One exams of the City & Guilds Sound Engineering (1820) course.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Sound waves

Part 1

What are sound waves?

Definitions

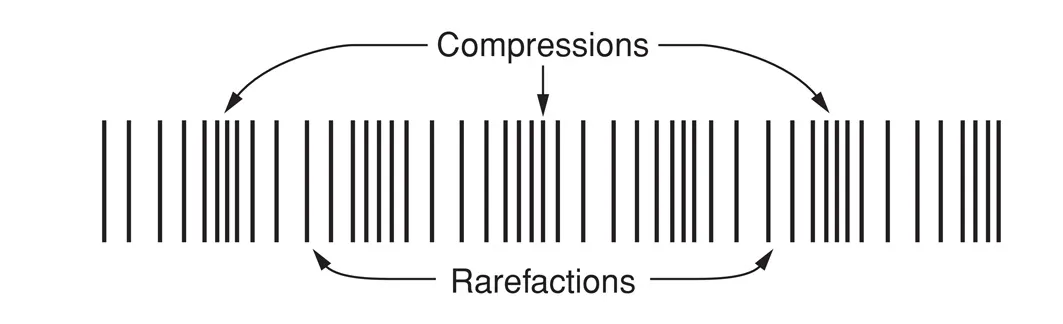

- Compression – a region where the air is compressed. In sound waves the compression is very small indeed.

- Rarefaction – the opposite of a compression. The air pressure is slightly lower than normal.

- ‘Steady barometric pressure’ – the normal air pressure of the atmosphere.

Frequency

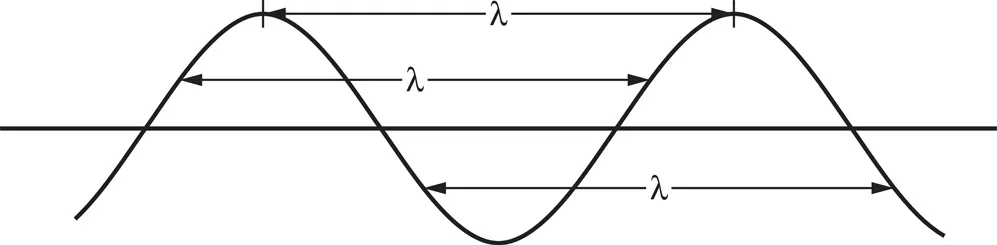

Wavelength

Amplitude

The velocity of sound waves

Velocity, frequency and wavelength

Important

Sound waves and obstacles

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- About this book

- 1 Sound waves

- 2 Hearing and the nature of sound

- 3 Basic acoustics

- 4 Microphones

- 5 Using microphones

- 6 Monitoring

- 7 Stereo

- 8 Sound mixers

- 9 Controlling levels

- 10 Digital audio

- 11 Recording

- 12 Public address

- 13 Music and sound effects

- 14 Safety

- Copyright

- Miscellaneous data

- Further reading

- Answers

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app