![]()

![]()

123 Be Transformed

In an article in the Christian Science Monitor, I came upon the phrase, “the trance of non-renewal.” It referred to organizations and communities that are satisfied with things as they are.

It is as though the system were asleep under a magic spell. A feature of the trance of non-renewal is that individuals can look straight at a flaw in the system and not see it as a flaw. Although the organization that is gravely in need of renewal may show many signs of its threatened condition, the signs cannot be seen by those who are under the spell.

It occurred to me that a variation of this kind of problem may be stalking some of you aspiring artists who may need to improve your drawing ability yet being under “the spell,” are unable to see the flaw, or worse, look right at it and not see it as a flaw.

One reason I think this might be possible is that most of us are fairly private in developing our talents. Part of it is a downright reluctance to have someone else see our mistakes and shortcomings; part of it is that innate quality that says “ I can do it myself.” The isolation that this kind of philosophy leads to is a narrower and narrower view of the problem. Living with the sameness of our drawings and our drawing ability month after month is a trance former. The trance envelops us slowly so that we are eventually numbed into an inability to spot our defects.

If such is the case, there is a need to be trance-formed (transformed). But how to do this? Especially if you don’t feel a need to improve, or if you do — don’t feel you have the time and energy to act on it. There may also be that debilitating cult of “waiting for the light to come on.” Believe me, the light isn’t going to “come on” — you have to turn it on yourself. If you have neglected your drawing improvement badly, you may figuratively have to back up and do some rewiring so some electricity can get through. The longer you wait, the harder it will be to break the trance and the less time and energy you will have to do it.

Also you will have filled your life with other, albeit important, activities that become your lifestyle — your bag of habits. A friend once told me “You do what you are in the habit of doing.” That statement has helped me greatly in avoiding habits that would eat into my valuable time. Once habits are formed they seem as natural as going to sleep and waking up. In time enough, habits will be formed to fill your days so you are entranced into saying, “I don’t have time to study drawing.” Perhaps only a few of you fit fully into that category, but still to some degree or other we’re all a little bit “trancey.”

I enjoy being critical. I’m being paid to criticize your drawings (of those who come to the evening classes), but only to search out a way to help improve your concept of drawing. I put it that way because drawing originates as a mental concept. In the evening classes I can spot evidences of trance malignancy. Most of it is caused by habit, the habit of approaching all drawings in the same way, but not always the best way. It’s difficult to change a habit; especially if it’s an old and comfortable one. I approach drawing instruction by trying to change one’s method of seeing; that is, looking at a pose or gesture as a “story.” This should encourage you to draw the idea behind the pose and not attempt to copy the model, line by line. Copying the outline and the details on the model remind me of a person working a crossword puzzle by blowing up the solution and pasting it on the blank puzzle, completely oblivious of the “story” or the meaning of the words.

Drawing should be fun. When I say drawing, I’m talking about grappling with a graphic depiction of some bit of story. I’m talking about digging down deep into your mental resources and coming up with a drawing that tells that story in a sensitive, exciting, and clear way; all the parts of it contributing to its efficacy; every line working in relation to every other line to compliment the whole. Nothing trancelike in that.

Artists are able to do that. They are an especially sensitive lot. Recently I was reviewing the book, A Poetry Primer, by Gerald Sanders.

In the first chapter he attempts to describe the “poet.” In my mind I substituted the word “artist” wherever “poet” appeared and it seemed very apropos. Here is the passage with the word artist inserted:

In the first place, the artist has an exquisitely sensitive mind that makes him alive to nuances that escape the average person. He is aware of nice distinctions in both the inner and outer worlds — nature and the mind — and apprehends subtle influences that pass unheeded by prosaic folk. Bits of knowledge, inappreciable experiences, evanescent emotions of which a blunter consciousness is scarcely cognizant, he seizes upon and uses. Thus he is often able to trace more obscure causes and to perceive more distant effects than others usually do.

He also has a fine memory — not perhaps for names and telephone numbers, but for whatever he has experienced of action and emotion in the world around him or in his own mind. Wordsworth, for instance, says that drawing “takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” But to the average person such experiences tend to recede with the passing of time and to become nebulous and indistinct. The artist, on the other hand, seems able long after the event to recall his experience and reproduce an emotion with the same acute consciousness as when they were new.

He has a wider and more varied experience than most men — the result, first, of his great sensitivity; secondly, of his ability to observe man and nature closely; and thirdly, of a deep sympathy, which enables him to enter easily into the experiences of others. Nothing seems too great or too small for his attention; further, he possesses in an extraordinary degree the ability to integrate his wide experience. By means of a powerful imagination, which acts upon the jumbled mass of information in his mind, he is able to create new experiences, to combine incongruous elements in such a way as to produce harmonious effects, and from old ideas to secure new connotations.

In addition he has the happy faculty of expressing his ideas and emotions in adequate images. This is one of his rarest attributes, for the expression of emotionalized experience in fitting graphic form is the culmination of man’s ability to communicate, and in this the artist is supreme.

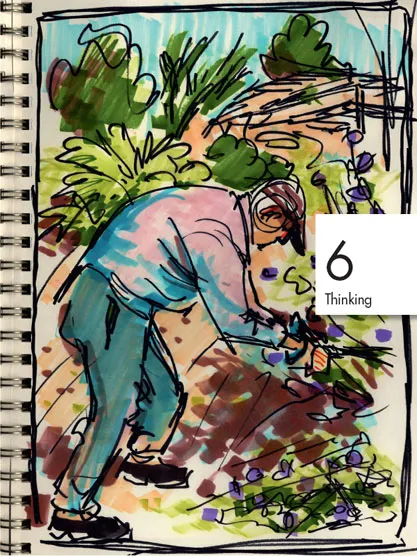

I’m afraid I’ve gone and gotten wordy again. So to win back your affection, here are some drawings to feast your eyes on. The first group was drawn by Pres Romanillos. These were done on a night when I badgered him to loosen up. He did, and the results are marvy. They are, on the Stanchfield scale of one to ten with ten being best — a ten. The second group is by Ash Brannon, who is no longer with us, but hopefully will return when he has completed his desired schooling.

![]()

124 Be Relentless

I have been trying to pin down the difference in attitude that it takes to switch from copying the model (or model sheet) to creating from the model. At best, everything that has turned up has been either nebulous, arcane, or ethereal (to me it’s all very concrete). But I am relentless. A couple of times I used the right and left-brain activities to clarify it. Simply put, the left brain loves to name the parts and place them in their proper places, which can be factual but sterile. On the other hand, the right brain is not interested in the parts per se (anatomy, for instance), only in so far as they can be assembled into some desired use; to bring meaning to them, or better yet, use them to create something meaningful. The left brain couldn’t care less about telling a story. It only cares that the proper language was used or the parts are authentic. The right brain will gladly sacrifice scrupulous adherence to facts, as long as it can tell a story or describe a mood or gesture. To accomplish this the right brain will even stretch the facts, that is, caricature them.

True, as Glen Keane pointed out recently, knowing the parts well will help in many ways, especially in building confidence. This means if you know your anatomy well, you are free to manipulate it to your purposes. Whereas if you don’t know your anatomy you are striving to capture it as you draw and deflecting your attention from what should be your goal — storytelling.

I continue to rack my brain for other ways to help you break away from copying. Here is another one prompted by the current persimmon season (I’m a persimmon addict). An unripe persimmon has all the physical parts of a respectable persimmon but will cause your mouth to pucker up if you bite into it. But when the fruit looks like it’s ready to be thrown out, then a bite of it yields its true essence.

While we’re on food, how about an apple pie. The apples, the sugar, the flour, and the printed recipe are certainly all factual ingredients but hardly say, “apple pie,” as yet. It’s a real expressive apple pie, though, when it comes out of the oven, warm and toasty looking, with that fresh baked apple and cinnamon odor wafting forth — that’s apple pie!

Try this one. Consider the picture screen on your television. There are adjustments to manipulate when the picture is unclear. One knob controls the vertical hold, one the horizontal; one knob adjusts the color, one the hue, and one the intensity of the image. When all the knobs are adjusted properly, you get a clear picture. When drawing there are several “knobs” that need to be constantly adjusted — they clarify the image in a way that will help transfer it to paper. They are the principles of perspective. When any or all of them are off, you will have various combinations of flatness, tangents, parallels, direction-less lines, nebulous or missing parts necessary to tell the story, ...