![]()

Part 1

Theoretical Background

![]()

Introduction

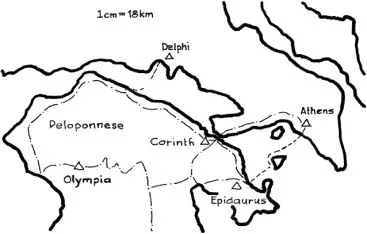

The focus of this chapter is the Sanctuary at Epidaurus, the most celebrated healing centre of the ancient world. The Sanctuary at Epidaurus was a city structure designed to promote health and well-being. It was built over many generations by some of the most well-known architects of the day. Like most great achievements in urban design it was not the product of one designer’s mind but the effort of a community spanning many generations. For over 1000 years people came to Epidaurus, this beautiful but remote spot, to worship at the sanctuary of Asclepius and to seek healing through spiritual renewal (Figure 1.1). The authority of Asclepius as the most important healing god in antiquity brought to the sanctuary and to the city-state of Epidaurus great financial prosperity. This wealth and prosperity in the fourth and third centuries BC was the economic foundation for an ambitious building programme involving some of the best architects, artists and craftsmen of the time. Some of the questions addressed by this chapter include the following. How did Epidaurus achieve its healing sense of place? What was so special about it that attracted so many in pursuit of health, well-being or spiritual renewal, the act of recreation? More specifically, is there anything we can learn that is applicable two millennia later when medical knowledge is so much greater?

Figure 1.1 Location of Epidaurus

In urban design, planning and geography, there have been countless studies on the meanings places have for people. Places can have many meanings: the main square in the city centre that gives a sense of civic or municipal pride; the great piazza at the focus of a religious organization, the goal of pilgrimage, that gives meaning and purpose to life; or the more humble village green that gives a sense of security and belonging (Moughtin and Mertens, 2003). Some places like Epidaurus develop health as their meaning, their raison d’être. As discussed in the Introduction to this book, Gesler (1993, 2003) identifies four healing environments, each of which contribute to the ‘therapeutic landscape’; they are the natural environment, the built environment, the symbolic environment and the social environment. Using this simplified description of a complex concept, ‘the environment’, it is possible to analyse a place in terms of the contribution of each aspect of the environment to the making of the ‘therapeutic landscape’, or in the case of this book the ‘therapeutic environment’. The central concern of urban design is the built environment: it is the area of health planning, over which those engaged in the city design professions have most direct effect. It is therefore apposite for a book focused on urban design to start with the built form of Epidaurus before moving on to other equally important environmental factors in the development of Epidaurus as a therapeutic environment.

The Built Environment

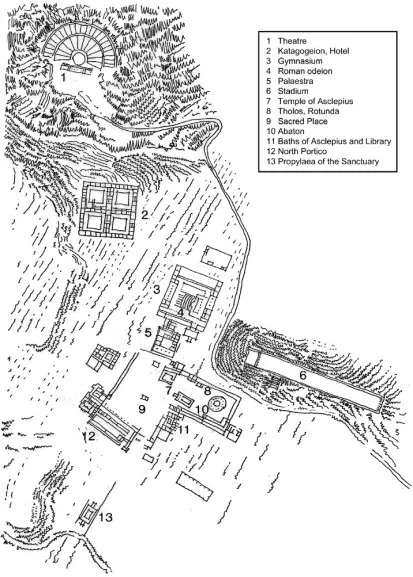

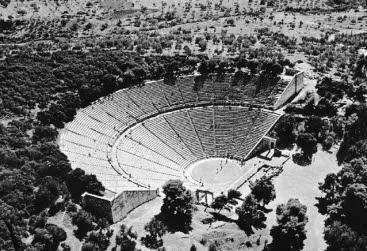

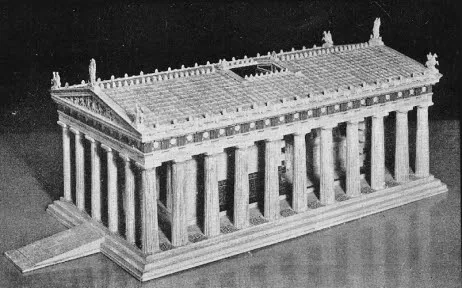

Epidaurus is now an archaeological site of tremendous riches (Figures 1.2 and 1.3). So important is the site that it was included in the World Heritage List in 1988. The great semicircular theatre, in a fine state of preservation, still hosts festivals and dramatic performances (Figure 1.4). Fortunately Pausanius visited Epidaurus in the middle of the second century AD. Pausanius, with the skills of a travel writer, recorded a thorough and accurate description of the sanctuary as it was then. His document is drawn on heavily for an appreciation of the urban form of Epidaurus (Pausanius, Penguin Edition, 1971, translated by Peter Levi). The excavation of the site has revealed some of the fine architectural detailing and the sculpture with which the buildings were decorated (Figure 1.5). In addition, the reconstruction of the site by scholars brings to life what must have been a truly wonderful city. Such reconstructions help us to imagine, to some extent, the grandeur of Epidaurus (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.2 Plan of the Sanctuary of Asclepius.

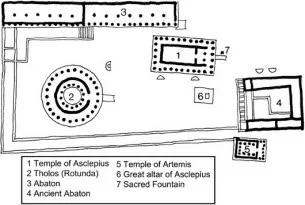

Figure 1.3 The main buildings in the Sanctuary.

Figure 1.4 The Theatre in its setting. (Photograph by McCaughan)

Figure 1.5 Architectural detail. (Source: Papadakis, 1976)

Figure 1.6 Temple of Asclepius (Source: Fletcher, 1950)

According to Pausanius (1971, ibid.: 193–4), the sacred grove of Asclepius was surrounded by boundary stones and ‘inside that enclosure, no men die and no women bear children: the ritual law is the same as it is on Delos’. The entrance to the site was from the north at the meeting point of the roads from the port of Epidaurus on the sea and from Argos inland (Figure 1.2). The Propylea or portal was erected in the fourth century BC. It was fronted by six marble Ionic columns and had six Corinthian columns on the inside. Visitors passed through this grand portal then processed along the Sacred Way to the centre of the composition, the temple of Asclepius built under the supervision of the architect Theodotos in about 380 BC. The other main buildings of the inner sanctuary of Asclepius were the Tholos (rotunda) built in 370–330 by Polycleitos the Younger and the Abaton (dormitory) (Figure 1.3).

The Tholos, a circular building, was surrounded externally by a colonnade nearly 22 metres in diameter with 26 Doric columns. Behind the colonnade was the circular wall of the sekos decorated with paintings by the famous artist Pausias. ‘A round building in white stone called the Round House … is worth a visit … Inside is a picture by Pausias in which Eros has discarded his bow and arrows, and carried a lyre instead, ‘‘Drunkenness’’ is also there, painted by Pausias drinking from a wine-glass; you can see awine-glass in the painting and a woman’s face through it’ (Pausanius, 1971, ibid.: 194). Seeking health and well-being at Epidaurus obviously did not exclude fun and pleasure. The Tholos was probably one of the most perfect and gracious monuments of ancient Greece, or in the words of Pausanius, ‘worth a visit’. The precise function of the Tholos is unclear, though some think its subterranean labyrinth was the tomb of Asclepius.

To the north of the Tholos was the Abaton (dormitory) where the visitors slept in order to see the god in their dreams and so be healed. The Abaton, in part two storeys, was 70 metres long, taking the form of a stoa (Figure 1.3). At the north of the Abaton was the sacred fountain mentioned by Pausanias (ibid.: 195), ‘a fountain-house worth seeing for its fine ornament, particularly the roof’.

The third of the sacred monuments was the Temple of Asclepius. Inside was the image of the god ‘The statue of Asclepius is half the size of Olympian Zeus at Athens, and is made of ivory and gold; the inscription says it was made by Thrasymedes of Paros, son of Arignotos. He sits enthroned holding a staff, with one hand over the serpent’s head, and a dog lying beside him’ (ibid.: 194). The temple was built in the Doric order, nearly 25 metres long by 13 metres wide. It was peripetral – that is, surrounded on all four sides by a colonnade. It had six columns on its front and back, beneath the pediments, and 11 along its sides. The temple was built about 380 BC under the supervision of architect Theodotos, who was also involved with the construction of the famous Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

Other buildings within the main boundary of the Sanctuary include the Xenon or Katagogeoin (hotel), the Stadium, the fourth century Gymnasium, a huge construction of about 75 by 70 metres. Later during the Roman period an Odeion was built in the interior of the gymnasium. By far the most magnificent monument, still in a state of good preservation, is the Theatre, designed by Polycleitos the Younger and built in the fourth century BC. This elegant structure dominates the site (Figures 1.2 and 1.4). The illustrations speak for themselves; nevertheless, the last word on the magnificence of the Theatre is left to Pausanius (ibid.: 195). ‘The Epidaurians have a theatre in their sanctuary that seems to me particularly worth a visit. The Roman theatres have gone far beyond all others in the whole world; the theatre at Megalopolis in Arcadia is unique for its magnitude; but who can begin to rival Polycleitos for the beauty and composition of his architecture?’ Polycleitos sited his building on the slopes of Mount Kynortion in a location with exceptionally good acoustics. Its seats cut into the rock and face north, so that the audience could contemplate the vast array of great monuments in the sanctuary and the magnificent panorama of the wooded landscape surrounding them. This is still a view to lift the jaded spirit. The theatre had seating for about 14 000 people. The auditorium in the form of a segment of a circle greater than a semicircle partly encloses the orchestra, which is a complete circle approximately 20 metres in diameter. Despite the great size of the theatre its form is perfectly harmonious and its acoustics without flaw. To repeat Pausanius, even today, 2500 years since it was built, it is still ‘worth a visit’.

Greek buildings were designed as a harmony of parts, all in proportion and with due measure: a perfect backcloth for the ideal healthy, harmonious life. ‘Medicine must indeed be able to make the most hostile elements in the body friendly and loving towards each other … it was by knowing the means by which to introduce ‘‘Eros’’ and harmony in these that, as the poets here say and I also believe, our forefather Asclepius established this science (art) of ours.’ So said Plato in Symposium through the mouth of Eryximachus, a member of an old family of doctors (Papadakis, 1976). For a different translation see Plato: The Symposium, translated by Christopher Gill (1999:19). Plato goes on to mention music, gymnastics and agriculture as means to achieve health and well-being or the balanced life.

The Sanctuary at Epidaurus is a magnificent example of city planning built over many generations on a grand but human scale: it is a subject for urban design in its own right. Like any spa town or recreation centre built since its foundation there was much to occupy the time of the visitor. Pleasure was mixed with spiritual or healthy renewal: the surrounding groves and mountain landscape were a source of exercise and fresh air, while the Gymnasium and Stadium were both a source of alternative more formal or demanding exercise. In addition, the Theatre, the Library together with the frequent sports events and festivals were sources of entertainment, amusement and diversion. Set in its dramatic landscape, the Sanctuary of Epidaurus was fully equipped physically for the holistic practise of medicine, as it was then known.

The Natural Environment

Many societies around the world believe that nature has healing powers. For example, we will read later, in Chapter 6, about the poetry of the eighteenth century in England, which extolled the virtues and restorative powers of nature. There are many today who feel that spending time out of doors or communing with nature in some remote place restores physical, mental and spiritual balance: that, somehow, being surrounded by undisturbed nature is a healing process. According to the ‘biophilia hypothesis’, which advances the notion that since humanity evolved in close association with nature, indeed as part of it, people therefore have an affinity for, and are comforted by, nature. We in Britain have developed an ideology that contrasts the restorative powers of the rural idyll and its healthy lifestyle with the pollution and stress of the great city, the ‘dark satanic mills’ of Blake. Clearly, there is a widespread belief that nature has healing powers and for this reason alone – that is, the strong belief in its powers – close proximity to nature may be beneficial for the health of individuals. In Chapters 2 and 3 we will examine the empirical evidence that supports the assertion that exposure to nature is therapeutic.

In Greek and Roman times the Sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidaurus was a relatively isolated place. An attraction of Epidaurus was probably its remoteness for those seeking to be made spiritually whole. It was a place where the supplicants could come directly into contact with wild and untouched nature. It was approached by land or sea through the small port town of Epidaurus, located on the Argive peninsula (Figure 1.1). The two nearest and most powerful states were Athens, which was 30 miles by sea from the port of Epidaurus, and Corinth, which was a distance of 18 miles by land. The Sanctuary of Epidaurus was a further nine miles inland from the port and connected to it by dirt track, which meandered through a wild, harsh and rugged wilderness. The softer landscape that was the immediate location of the Sanctuary was a perfect setting for the recreation of body and mind, exemplifying the romantic notion of the healing powers possessed by idyllic rural settings.

Specific elements taken from nature are thought to posses healing powers. Chief amongst them is water. Most of the world’s great centres of healing are associated with a stream, a river, a lake, or hot and cold springs. Many are sited near a spring with allegedly medicinal powers. In some cases the spring magically appears. Lourdes is a particularly good example of a holy shrine built around the site of such a spring. In this country we have St Winifred’s Well in Holywell, North Wales (Figure 1.7). In Holywell, St Winifred literally ‘lost her head’ to an unwelcome and rather barbarous suitor. At the place where head and body were miraculously reunited a spring arose. Since that time St Winifred’s Well has attracted to its very beautiful rural precincts many seeking cures or solace. Water is also associated with the process of cleansing the body and soul, with rebirth and baptism: more simply, it may be appreciated for its aesthetic qualities or for the pleasure and fun it affords the users (Moughtin and Mertens, 2003, op. cit.).

Figure 1.7 St Winifred’s Well, Holywell, North Wales.

Vitruvius (Dover edition, 1960), writing in the first century AD (Book 6: 225–42), discusses the properties of water and its importance for building. He also described water as ‘the chief requisite of life’. In particular, Vitruvius pointed out that settlements, including of course those involved in promoting health such as Asclepion sites, should be near fresh spring water and away from sources of pestilence. Epidaurus was fortunate in this wonderful gift from nature, water. Such a gift was vital for any settlement in Greece, a land not blessed with plentiful rain. The water of Epidaurus, like Evian water, possessed special properties, but more importantly it was an essential part of the ritual of purification: to the Greek its use represented a purification of the soul in preparation for communion with god and achieving the eventual goal of becoming whole or healthy.

The Social Environment

Healing is a communal act. It involves physician, patient, family, friends and members of the wider community. The actors in the process of healing play various roles. This process and the roles played vary from culture to culture. However, what appears to be important for healing, in all situations, is that there is equality between those healing and those being healed. That is, there must be ‘feelings of mutual respect and trust’ between doctor and patient (Gesler, 2003, op. cit.: 15). It is this ideology of equality in social relationships which is essential for a healing environment.

At the Sanctuary of Epidaurus, the social environment – that is, the con...