1

The development of Singapore’s colonial economy

There was more to the foundation of the British colony of Singapore in 1819 than a stroke of brilliance by Thomas Stamford Raffles, who is usually credited with the creation of the city. We are occasionally apt to forget that the city is located in Asia and is largely populated by Asians. At the time, it was also a vital part of the Asian maritime economy and should be seen as the heir of a long line of Asian maritime trading centers located in or near the Straits of Melaka. Singapore’s history, properly understood, can be traced back to the Malay entrepôts of Srivijaya and Melaka. Moreover, it is clear from recent archaeological work that the island itself was the site of an entrepôt that flourished as early as the fourteenth century (Miksic 1985). Between then and the nineteenth century, there was always an important Malay entrepôt in the immediate vicinity. Whether at Riau, on the island of Bentan, on the Johor River or at Melaka itself, this part of the Straits was an area of vibrant economic activity.

Nineteenth-century Singapore played a number of roles: some traditional, some innovative. Much that has been written about the city has stressed its innovative aspects, often to the extent of exaggerating their importance. John Crawfurd, who was the Resident Councillor (then the chief administrative officer) of the colony from 1824 to 1827, emphasized the British role in the success of the colony: “Few as the British settlers of Singapore are [there were only eighty-seven resident Europeans in 1827], they constitute in reality the life and the spirit of the settlement; and it may be safely asserted, that without them, and without their existing state of independence and security, there would not exist either capital, enterprise, activity, confidence or order” (Crawfurd 1987:553). While there is some justification for Crawfurd’s boast, it does not fully explain the colony’s early or continuing success. After all, there had been a number of attempts at founding British settlements in Southeast Asia during the late eighteenth century, and most of them were dismal, if not disastrous, failures.1 Even Penang had never fulfilled its original promise.

Singapore’s success owed much to its location, and because of this, it filled many of the roles played by the earlier Malay entrepôts. It drew together the east—west trade between China and India and points further west. It also acted as a gathering point for the products of Southeast Asia: the sea products of the islands and the coasts, and the rice, pepper, spices, forest produce, tin and gold of the inland areas. These commodities, many of them unique to tropical Asia, found markets throughout the world. From age to age, a port had arisen in this part of the Malay world. Whether located on what O.W.Wolters called the “favored coast” of eastern Sumatra or on the Malayan peninsula, or in the Riau—Lingga Archipelago, it serviced the trade and produced wealth, power and culture for its overlords. It was the city “below the wind” or di-bawah angin: the city at the end of the monsoons and the beginning of others, as Tome Pires called Melaka (Cortesão 1944). In the past, such cities had been dominated by Malay rulers and the maritime peoples of the region. In the nineteenth century, even though it was under British rule, Singapore shared fully in the trans-Asian, maritime trading culture that had a heritage of over fifteen centuries.

Singapore also partook of the heritage of another type of city. Since the sixteenth century, a new type of port had also arisen: these were the colonial castle towns of Melaka, Manila and Batavia. These were centers for the concentration of European power, bases for navies and imperial expansion. Their superior firepower and fortifications guaranteed a level of security for European activities that would have been impossible in other ports.2 In particular, European companies and traders could amass wealth and dispose of capital on their own terms.

Even though Singapore had aspects of both types, there were key differences. For Raffles, Singapore was to be a refutation of the policies of monopoly, trade restriction and territorial expansion that he saw practised by the Dutch and Spanish. His focus was on free trade and the avoidance of territorial governance. Despite sporadic attempts at constructing fortifications, Singapore has never had a castle. In the stress on free trade, Singapore was more like its immediate predecessor, the nearby port of Riau. In fact, if we look more closely at eighteenth-century Riau, it may be argued that Riau was the real predecessor, bringing not only the traditions of the Malay port-polity but also a complex of Asian trading patterns and networks that had been newly established during the eighteenth century.

What was Riau? The eighteenth-century predecessor of Singapore was the Malay/Bugis center of Riau, located near the present town of Tanjong Pinang on Bentan Island, just 50 kilometers south of Singapore. Its formal ruler was the sultan of Johor, whose state was the inheritance of the Melaka sultans. Riau pulled together three of the major trading streams of eighteenth-century Asian commerce and allowed the emergence of a number of new features. First, although it was located in the Straits and populated by many Malays, Riau owed much of its commercial success to the Bugis. These were traders and pirates who had become princes3 and had come to dominate the Malay negri of Johor/Riau in the eighteenth century. The Malay sultans, Mahmud III ( c. 1760–1812) and his successors, were largely under the domination of the Bugis Yang di-Pertuan Mudas and their families. The other Malay princely families, like those of the Temenggong of Johor and the Bendahara of Pahang, were pushed to the fringes. At Riau, the interlopers brought together the far-flung trading networks of the Bugis traders and warriors, whose activities made them a major force throughout much of island Southeast Asia (Andaya 1975; Trocki 1979).

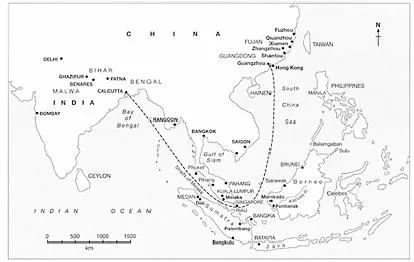

The second principal element in the Riau economy was the Chinese junk traders and the large number of Chinese laborers who had settled on the island to produce pepper and gambler. During the eighteenth century, the Chinese junk trade of Southeast Asia, based largely in the ports of Fujian province and the Teochew areas of Guangdong province, had greatly expanded as a result of the Quangxi boom. So great was China’s demand for Southeast Asian goods that it had become necessary to rely on colonies of Chinese laborers to produce them. By the end of the eighteenth century, the coasts of Southeast Asia were dotted with such outposts of laborers. Riau was thus part of this “water frontier” of Chinese expansion, which stretched around the coast of the South China Sea from southern Vietnam to Batavia (Cooke and Li 2004). There were tin miners in various parts of the Malayan peninsula and Bangka; gold miners in Pontianak, Sambas and Kelantan; and pepper planters in Chantaburi, Trat and other towns around the Gulf of Siam, Brunei, Terengganu and elsewhere. There were sugar planters in Kedah, and there had also been a thriving colony in Java until the massacre of 1740, when the Dutch killed most of them (Trocki 1990; see Figure 1.1 for details of the British trade route from Bengal to Guangdong and the Chinese settlements in Southeast Asia, c. 1780).

These settlements represented a new phase in the Chinese relationship with Southeast Asia. In addition to being a new and more productive presence in the region, their labor provided a new source of income and wealth for the indigenous and European colonial rulers. At the same time, the existence of large numbers of Chinese concentrated in specific locations, often far away from urban centers, would come to present new challenges in terms of assimilation and control for those rulers. For Singapore, the trade of these settlements and the flow of Chinese labor in and out of them would become the life blood of the port.

The colony of pepper and gambier planters at Riau would come to form an important element of Singapore’s economy and population. Gambier was a shrub that was grown in conjunction with pepper, making both viable economic enterprises. The gambier leaves were boiled and the decoction reduced to a hard paste, which was packed and sent to China, where the highly astringent substance was used in tanning leather and as a dye. I have estimated that by the late eighteenth century there may have been as many as 10,000 Chinese settled on Bentan Island, most of whom would have been engaged in this industry (Trocki 1979).

The third new element in the economy of the region was the Europeans, in particular the British. Europeans had been an important presence in the region since the beginning of the sixteenth century, and they had demonstrated an ability to carve out economic niches for themselves, sometimes to the disadvantage of Malay and other local rulers. Thus the Portuguese had seized Melaka, the Spanish had created Manila and the Dutch had set up Batavia. All functioned as fortified centers for the expansion of European power and the enforcement of monopolies. On the other hand, all had really opened themselves to the junk trade and despite monopolistic practices had provided a focus for the Malay, Bugis and other “native” trade. The Spanish and the Dutch, with their access to New World and Japanese silver, also brought important infusions of capital into the area. Sometime before the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Spanish silver dollar had become the universal currency of the South China Sea trading zone.

Figure 1.1 Map showing India, Southeast Asia and China with the British trade route from Calcutta to Guangdong and the Chinese settlements of Southeast Asia, circa 1780

British activity in the second half of the eighteenth century added a new and significant element in the Asian trade. The forerunners of free trade, the British “country traders” came to form a key component of the triad of economic networks that had gathered around Riau. These traders, usually based in Bombay, Madras or Calcutta, carried cargoes of Indian produce intended for exchange for both Southeast Asian goods (pepper, spices, tin, forest produce, pearls, etc.) and Chinese goods, primarily silver. They made dangerous, epic voyages in large, well-armed vessels, “country wallahs” as their ships were called. These sometimes took two to three years to complete, with stops at both colonial and indigenous ports throughout the islands. Their ports of call included Aceh, Kedah, Phuket, Linggi, Melaka, Riau, Terengganu, Sambas, Pontianak, Banjarmasin, Brunei, Batavia and Sulu. By the 1780s, they had been joined by the Americans, who now came seeking their own supplies of pepper and tea (Furber 1951; Lewis 1995).

Until it was destroyed by the Dutch in 1784, Riau in particular was a crucial port of call. In addition to being strategically located at the entrance of the Straits of Melaka, it gave country traders the opportunity to meet Asian traders from all points to the east. They could turn over considerable portions of their Indian cargoes, particularly textiles, weapons, gunpowder and opium. At the same time, they could load up with Riau’s pepper, Bangka and Selangor tin, and the usual range of forest and sea produce, all of which were in demand in China. Under its Bugis rulers, Riau was virtually a free port, and charges were minimal; however, if it was low-cost, it was also somewhat insecure for European shipping.

In their Indian bases, the country traders formed partnerships with Parsees, Banjans and Muslim merchants on the one side and linked up with covenanted East India Company (EIC) servants on the other (Bulley 2000). They operated at first with the grudging sufferance of the EIC but later became indispensable to the company. They specialized in carrying certain products that the East Indiamen decided not to carry. In particular, they pioneered the opium trade. The security of this trade was probably one of the key motivations behind Raffles’ decision to found a port at the eastern end of the Melaka Straits. He was, after all, a servant of the EIC and was operating under the direct orders of the Governor-General.

By the early nineteenth century, much of the British Indian economy had come to depend on the profits from the opium trade to China, control of the drug having fallen into British hands following the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Groups of EIC servants in the towns of Patna and Ghazipur had seized the monopolies over opium cultivation in the surrounding districts. In the 1780s, Warren Hastings had taken over the monopoly on the company’s behalf, and Lord Cornwallis had then formalized the EIC’s control of its production. Between 1780 and 1820, the EIC produced an annual average of about 4,000 chests of both Benares and Patna opium combined. Although the price had fluctuated considerably, by 1820 it was valued at over $1,000 per 140 lb ( c. 63.6 kg) chest (Trocki 1999).

Although a good portion of the annual “provision” was traded in the various ports of Southeast Asia, the greatest bulk of it was sold, illegally and clandestinely, in China. The opium trade had been illegal in China since 1729, thus the EIC took no part in handling the contraband merchandise. The annual production of opium was gathered in Calcutta and was auctioned to the country traders and their agents in a number of lots over the course of each year. From that point on, the company ostensibly had no part in the trade. On the other hand, the country traders, after disposing of their illicit cargoes at Macau or Whampoa, found themselves with large amounts of silver on their hands, and rather than carry it back to India, they deposited it in the company’s treasury in Canton. For their deposits they took bills of exchange, which were negotiable in Calcutta, Madras, Bombay, and ultimately in London, New York and elsewhere in the world. These “India bills” became one of the world’s first truly global currencies. By the mid-nineteenth century, opium profits greased the commerce of the entire Western world. On the other hand, in Canton, the EIC could now use the silver to cover its annual tea purchases, thus wiping out what had been a chronic balance of payments problem for the company during most of the eighteenth century.

The opium trade, which in 1819 had come to represent an annual flow of silver amounting to about $8 million, was highly vulnerable. Despite their firepower, the country ships had no secure base between Calcutta and Canton. In 1782, the EIC ship Betsy was seized at Riau by combined French and Dutch forces (with the compliance of the Riau ruler), costing the company nearly 1,500 chests of opium among other things. Such experiences led the EIC to leave the country trade of Southeast Asia to the independent traders,4 but they also strengthened the resolve of the EIC and interests allied with it to find a secure base in Southeast Asia for the China trade.

It was in the shadow of these events that the country trader Francis Light, working on behalf of the EIC, established the settlement of Penang in 1786. Outside this port, the British China trade, as it was euphemistically termed in the documents of the era, continued to be at the mercy of undependable native and unfriendly Dutch governments. It was thus the security of this trade, in actuality the opium trade, that Raffles and his Indian superior, the Marquis of Hastings, saw as one of their key responsibilities in the atmosphere of 1818–19. Not to put too fine a point on it, we can say that the founding of Singapore was above all about opium.

Following the Napoleonic wars and the re-establishment of the Anglo-Dutch alliance, the British government, ignoring the “narrow interests” of the EIC, had restored the Dutch to their position in Southeast Asia prior to the war, returning to them Java, Melaka and other Dutch territories seized during the war. After being required to hand Melaka back to the Dutch in 1818 and being out-maneuvered by Dutch agents in making a treaty with the Yamtuan Muda of Riau, Raffles and his associate, Colonel William Farhquar, sought to found a new British settlement. They surveyed a number of sites at the entrance to the Melaka Straits and finally decided to make the bold move of signing a treaty with Temenggong Abdul Rahman of Johor.

The Temenggong had been one of those Malay chiefs who had suffered a loss of status and influence as a result of Bugis power at the Riau court. He and his followers had left Riau and were then occupying a site near the mouth of the Singapore River; according to Dutch reports of the time, they made a living from small-scale piracy. The Temenggong had also welcomed the settlement of a small group of Chinese pepper and gambier planters on the island whose numbers would increase rapidly in the coming years. Given the recent treaty between the Dutch and the Riau ruler, Johor and its chiefs were technically off-limits to the British, but despite Dutch protests, the settlement went ahead.

Agency houses and junk traders

Although it was a British initiative, the new settlement, with its policy of free trade, became a natural focal point for the trading interests that had formerly gathered around Riau. In a matter of months, the Chinese junk traders, Bugis traders and British merchants began to flock to Singapore. The combination of these factors certainly made the initial success of Singapore quite spectacular. Within five years, Singapore’s trade grew to a value of over $13 million annually (Crawfurd 1987:537). John Crawfurd argued that Singapore had contributed greatly to an absolute increase in British trade in Asia. Answering critics that Singapore simply drew trade from Penang, he pointed out that in 1818, the whole of direct British trade with the Straits of Melaka, and generally with the eastern islands, excluding Java, centered at Penang, totaled $2,030,757. In 1824, however, the joint exports of Penang and Singapore were $9,414,464, $6,604,601 of which was exported through Singapore ( ibid.: 549).

What was the basis of this sudden increase in British trade? Certainly an important share of it was opium. In 1823–24, $8,515,100 worth of opium was shipped to China. Even though not all of this was landed in the Straits, much of it was. Its location gave Singapore advantages that Penang could not match. In addition to serving as a base for British trade, it was better able to tap into the very active trade carried on by Chinese junks in the South China Sea and in the Gulf of Siam. Now, much of the trade that had formerly gone to Riau shifted to Singapore, and Dutch-controlled Riau became a backwater. It may have been true that British free-trade policies were an important attraction for Chinese traders, but so too was its open market in opium, which at that time was as negotiable as silver dollars all over Southeast Asia.

A second element related to the British presence was the arms trade. Throughout the first fifty years of its existence, Singapore and the other two Straits Settlements of Penang and Melaka were the major distribution points in Asia for arms and ammunition. In his description of Singapore’s trade, an incidental chapter to his report of...