![]()

A Study on the Effect of Cause-Related Marketing on the Attitude Towards the Brand: The Case of Pepsi in Spain

Iñaki García

Juan J. Gibaja

Alazne Mujika

SUMMARY. CRM is an effective tool for differentiating brands and for obtaining emotional positioning among consumers. However, an utilitarian use of this tool might be counteractive. This research aims to better understand the effect of CRM on attitude towards the brand. For this purpose,

Pepsi’s CRM campaigns in Spain have been analyzed. Results show that, unexpectedly, CRM campaigns might lead to adverse effects as a result of the mercantilist abuse of the concept of solidarity.

[Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website:

KEYWORDS. Cause-related marketing, attitude towards the brand, consumer skepticism, Spain, Pepsi

Cause Related Marketing

In a seminal piece, Varadarajan and Menon (1988:60) define CRM as “the process of formulating and implementing marketing activities that are characterized by an offer from the firm to contribute a specified amount to a designated cause when consumers engage in revenue-providing exchanges that satisfy organizational and individual objectives.”

Several European and American authors (Varadarajan and Menon 1988; Smith and Alcorn 1991; Andreasen 1996; Guardia 1998; Adkins 1999; Fundación Empresa y Sociedad 1999; Meyer 1999; Pringle and Thompson 1999; Welsh 1999; Recio and Ortiz 2000; Fundación Empresa y Sociedad 2001) point out that CRM can be an effective tool for differentiating brands and for obtaining emotional positioning among consumers. Its application would be of benefit to the interests of the firm as far as its market position, social reputation and brand image are concerned. The positive outcome experienced by corporations in this area has led to a continuous growth in CRM activities (Brown and Dacin 1997). File and Prince (1998:1537) conclude that CRM “has become an established part of the marketing mix in privately held companies, confirming the adoption of this marketing innovation in a new segment of business.” Smith (1994) states that corporate-NPO alliances, including CRM, are becoming the fastest growing form of marketing today. According to these authors, it seems as though causes, NPOs, corporations and society have benefited from corporate involvement with social issues.

In spite of its popularity, several authors (Varadarajan and Menon 1988; Andreasen 1996) warn that corporations involved in CRM activities might incur criticism and charges of potential abuse and exploitation of both causes and NPOs. Due to these reasons Webb and Mohr (1998) found that around half of the sample analyzed in their study expressed negative attitudes of skepticism or cynicism towards the firms that participate in CRM campaigns. Polonsky and Wood (2001) also advice that using CRM programs to merge social objectives with commercial objectives might lead to unexpected results. What they call “overcommercialization” of CRM may, in fact, harm those who should benefit from this new tool designed to support social causes.

In Spain, some current trends of CRM have also been criticized (García 2000a, 2000b; Ballesteros 2001) because it could be seen as a cynical use of solidarity with commercial aims. According to this argument, many of the Spanish firms that get involved in this kind of campaigns would do so, above all, in the hope that the image of the NPO with which they are associated will help to define, improve or repair their own image. To these authors the concept of solidarity might be spoiled as a result of its utilitarian abuse. Thus, CRM might become just another tool to improve brand image instead of making people aware of social injustices. In this light, CRM would not educate but would merely encourage consumption.

From the company’s point of view, CRM is certainly an instrument that can offer favorable commercial results in the short term. However, it may also seriously harm its image if the firm’s commitment to a cause is, in the long term, directly and exclusively linked to the firm’s product consumption. It may be for this reason that in Spain, an increasing tendency to detach CRM from strictly promotion-orientated actions is currently being observed.

Cause-Related Marketing in Spain

Spanish consumers’ purchase decisions are increasingly based on ethical and moral considerations. Tangible features of the product are no longer the sole purchase criteria. Spanish citizens show increasing sensibility towards social issues. According to a research carried out by Fundación Empresa y Sociedad1 (1997), 63% of Spanish consumers admitted this support to non-profit organizations for the last year. Fernández et al. (1999) also found that nearly 61% of those surveyed worked in aid of a solidarity cause. Therefore, one can argue that there is a positive attitude among Spaniards to help those in need. These studies also confirm that the Spanish youth show more solidarity than other age groups, and more than they used to some years ago. Another report from Fundación Empresa y Sociedad (2001) evinces the results for Spain of international studies “The Millenium Pool on Corporate Social Responsibility” and “European Survey of Consumers’ Attitude Towards Corporate Social Responsibility.” This report also reveals that consumers in general, and Spaniards in particular, have a good mind to reward those socially concerned companies. So, while the social responsibility of a company is a “very important” factor for 25% of Europeans when purchasing a product, in Spain the rate grows to 47%, rising to 89% if we take into account those who regard it as “important”, in contrast to the European average of 70%. Otherwise stated: consumers (especially youngsters) begin to wonder: Is the firm whose products I buy a “good citizen”? Spanish consumers are punishing “bad citizens” and rewarding the “good” ones.

Spanish consumers ask the firms to involve to a greater extent into social responsibility. It is for this reason that CRM has been undergoing a spectacular boom in the last few years. Proof of this is the fact that Fundación Empresa y Sociedad has declared the promotion of CRM campaign quality management to be a priority activity area. In this sense, it has recently created the “Solidarity Action” emblem, the first quality certificate for CRM programs in Spain (Fundación Empresa y Sociedad 1999).

The willingness of Spanish citizens to participate in CRM programs, especially those based on solidarity-orientated affairs, is very high. According to Fundación Empresa y Sociedad (1997) nine out of ten Spanish consumers are willing to pay more for products involved in a CRM campaign. They are also willing to switch brands when they are informed about the implication of a firm in a CRM campaign. However, even though Spanish consumers show excellent attitudes towards products associated with solidarity, they express a lack of confidence in the fund-gathering system used in CRM programs and in the final destination of funds. This implies an urgent need for the improvement of CRM program communication strategy in Spain (Fundación Empresa y Sociedad 1999).

Nevertheless, the recent and rapid acceptance of CRM by society and companies in Spain has not been sufficiently reflected in academic research. In Spanish marketing literature there are hardly any specific studies assessing the success of any particular CRM campaign. Barone, Miyazaki and Taylor (2000:249) also point out that “research is needed that provides insight into whether and when corporate sponsorship of social causes enhances brand choice.” Therefore, the aim of this research is to shed light on the potential effects of CRM campaigns on brand image. For this purpose, Pepsi’s CRM campaigns have been analyzed. The most relevant features of these campaigns are shown on the following pages.

The Pepsi Crm Campaigns in Spain

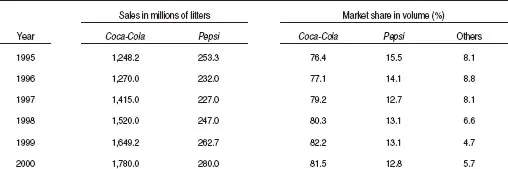

In 1997, PepsiCo-Spain obtained profits of approximately 3.6 million euros, while just one year before it had lost almost 43.3 millions (Salas 1998). The company thus emerged from a deep crisis which had started in the early nineties and which had seriously harmed the market share of its most emblematic brand–Pepsi–to the benefit of its eternal rival Coca-Cola (see Table 1).

Table 1. The Cola Refreshments Market in Spain

Alimarket (2001, 2000, 1999a, 1999b, 1998a, 1998b, 1996)

1998 was the year in which the good prospects for PepsiCo consolidated in Spain, with approximate profits of 12.6 million euros. The importance of this new prospect comes across clearly in the words of Yiannis Petrides, Chairman of the company in Europe and key man behind this change, when he stated that “after the United States, Spain is the country with the highest volume of business for the company. It is therefore one of the strategic markets for continued growth of a profitable kind” (Gómez 2000).

During its Spanish crisis, Pepsi had discovered that its drastic reduction in price with regard to Coca-Cola had only contrived to harm its quality image. According to the marketing director of Pepsi in Spain, after carrying out many market research studies, the company had discovered that the differences in the market share with regard to Coca-Cola could not be put down to taste, price or distribution network, but to something much more complex: brand image (Cabrero 2000).

Being aware of this factor, in the last few years the company has started an ambitious brand image construction strategy for Pepsi in Spain. Using the implicit message that “we are the alternative to Coca-Cola”, Pepsi wants to promote consumption among young Spaniards, introducing itself as a modern, non-conformist, provocative, rebel brand, which shares their concerns and values. As the president of PepsiCo for Europe states, “we shall maintain our policy of connecting with the younger generations by means of attractive advertising and promotion actions in environments this group feels most identified with: football, music and NPO cooper...