![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction – place, encounter, engagement

Context and themes

Russell Staiff, Steve Watson and Robyn Bushell

A prologue, a reflection, a flavour

Taking a very broad historical perspective, the relationship between travel and visiting special places is neither recent nor unusual, nor bound to particular geographies or cultures. Pausanias, in the second century CE, travelled to Greece and recorded his visits to religious sanctuaries. The Indigenous nations of Australia, prior to colonisation and today, in some places continue to mark their movements with a deep awareness of journeying and spirituality conjoined inseparably. Buddhist pilgrims criss-crossed Asia throughout the time of the Common Era. Medieval pilgrimages to the Holy Land and to places such as Santiago de Compostela, in northwest Spain, are well documented, as are the travels of young British male aristocrats on the Grand Tour in the eighteenth century. In these cases space, time and distance were thought to be governed by something profoundly significant and in each instance there existed a reciprocal relationship between the traveller and the place to which they journeyed, a relationship that resulted in a transaction of some kind.

Of course, the historical and cultural circumstances of these various travels to places considered special is vastly different, and any easy historicism is fraught. However, it highlights a degree of ordinariness about the quest to go to places considered out of the ordinary. It also points to the communicative nature of such journeying: conversations with the deities – symbolic, material, spiritual and knowledge interactions and engagements that intensify the sanctity of the place (whether sacred or secular). For the traveller, such engagements produce benefits: spiritual, aesthetic, educative, a sense of mental health or personal wellness, conversations with fellow travellers, encounters with those met along the way. The communicative act between special places, people and fellow travellers is invariably potent with representations. It’s always deeply an experience of the body and all its capacities for meaning making (intellectual, imaginative, somatic, sensual, emotional) and movement. Communication is often performed (or enacted), and the media used for transmission is about connectivity (not just the immediate connectivity of being in place but that which pulses along networks to those in other places or activates virtual paths that connect special places to other special places mentally and, today, in cyberspace). Further, the communicative act is about degrees of immersion where the subject’s identity is enmeshed in visual, verbal, sonic and somatic cultures. It matters little whether these immersions are manufactured for the traveller or simply the result of being enfolded in and by places that are semiotically charged and that are deemed to communicate on many levels, both physical and mental.

Such communicative transactions with special places invariably have far-reaching political dimensions and are demarcated by all manner of power relations. For the travellers, visiting places of spiritual power in ancient Rome or medieval Christendom, at stake was an exchange between the visitor/supplicant and the deity. A ‘trade’ that enhanced the power of the deity, its sacred objects/places and its institutions, rendered upon the traveller obligations, along with fervent hopes about the future and freedom from the past. In other times and places, travel to special places were journeys of imaginative geographies where Western Orientalist fantasies underpinned colonial ambitions and imperial power, where special places were conjured in ways that enacted an intricate and elaborate interweaving of power, desire, ideology, identity and landscape (always already visible to the traveller by a multitude of synchronous and diachronic communicative acts verbal, visual, aural and gastronomic). But other types of power were also manifest. The power of knowledge and the way special places have been marked out in academic disciplines, and then re-marked over and over in frenzies of representation that exhibit spatial intensities. And, simultaneously, there occurs the contestation of disciplinary knowledge and the writing over of place, like a palimpsest, with other knowledge formations that have different cultural or geographical origins to that of the dominant narrative: the power of economics and the way special places are not only valued but become nodes of concentrated economic activities. These places become entangled in complex webs of commerce that operate on a number of scalar levels of magnitude, at different speeds and along different paths of connectivity. There is the power of institutions, organisations and modes of governance that act as mediators and interpreters in the special place/traveller performance and that authorise particular choreographies of movement and particular knowledge productions. Then there is the power of the traveller to subvert all of this if they choose, to stray from the sanctioned routes, to act in contrary and rebellious ways, to make unauthorised meanings, to challenge the typologies that render places special, to misuse and disobey, to conjure as comical, to satirise, to re-make place and significance, to create new connections and paths, to invent new modes of representation, to mistranslate, to contrive and enact narratives so numerous that, paradoxically, they both challenge and add to the semiotic richness of special places.

Not once in this description have we mentioned ‘heritage’ or ‘tourism’. This is because to begin with ‘heritage’ and ‘tourism’ immediately privileges these terms, and often fails to register that ‘travel’ to ‘special places’ is one of the enduring legacies and characteristics of peoples of many cultures throughout history. We must remember, the descriptor – heritage tourism – is of recent coinage and conjures a particularity that both erases the vastly more important understanding that this prologue attempts to visualise and, at the same time, valorises the language of the tourism industry of recent decades (with its inescapable capitalist logics of production and consumption) where market sectors (and the promotion thereof) hold governance.

The chapters in this collection weave in and out between these two general conceptions: visiting places that are deemed special, for whatever reason, and the more determined focus awoken by the heritage tourism categorisation (even if applied critically). In so doing the essays keep in play analytical possibilities and theoretical positions that encompass a variety of ways heritage places can be thought of as being ‘an encounter’, ‘an engagement’.

Theoretical directions

To introduce this collection of essays requires more than the usual declamatory statement of objectives and intent. What it also needs, in our view, is a moment of reflection, not least because such moments form the very essence of this book. They motivated its planning, its inception, the discussions that provided momentum for it, and even its title. This reflection was prompted by the general state of affairs that each of us detected in our field of heritage and particularly heritage tourism – a state that seemed profoundly unsatisfactory, particularly in relation to the contexts of heritage tourism and the interactions between heritage places, tourism and tourists, interactions that are often reduced to matters of operations management or, at best, the modalities of interpretation. Where theory has shed light it is often by way of some taxonomic approach that deftly avoids more critical perspectives offered by and emerging in the social sciences. When engaging with the ‘key issues’, a kind of conceptual bricolage became apparent: a range of ideas that appeared to address facets of heritage tourism, but which never seemed to make any sense when seen as a whole. There seemed to us, therefore, to be a complacency around the received wisdoms that circled our field, from visitor management and interpretation to destination management and planning, marketing and operations, and all the other ‘stuff’ that fills our texts and lectures and our students’ minds.

To be sure, there are some meaty concepts that provide theoretical weight: authenticity, dissonance and the twists and turns of the ‘heritage’ debate. We are impressed by developments in the field of cultural tourism that have helped us to conceptualise both tourisms and tourists such that we could unpick tourist motivations, for example, and appreciate (to some extent) the statistical techniques that might be used to attempt to factor-analyse such abstract concepts as ‘destination image’. And, on a higher plane, we could be guided by the explanatory strength of the big theories: the completeness offered by structuralism with its analysis of power and authority and its discursive corollaries, the transparency of social process afforded by constructivism, the justice of postcolonial theory, the disruptions of postmodernism; each one of these leaving essences of thought and reflection that might in some sense (though not always clearly) be applied to what we do and teach.

In recent years new perspectives have emerged: non-representational theories, affect, mobilities, actor-network theory. Yet in the face of all of these theoretical developments, from the momentous to the prosaic, there seemed to be something missing. It was still not entirely clear what was happening around those ragged intersections of heritage, tourism and tourists that really interested us, nor what each of the theoretical movements outlined above could contribute to an understanding of them. In creating that moment of reflection we have had to dissolve some certainties, to revel in doubt and to fill the resulting space with a variety of thoughts and analysis, new directions and meanings, and that is the purpose of this book.

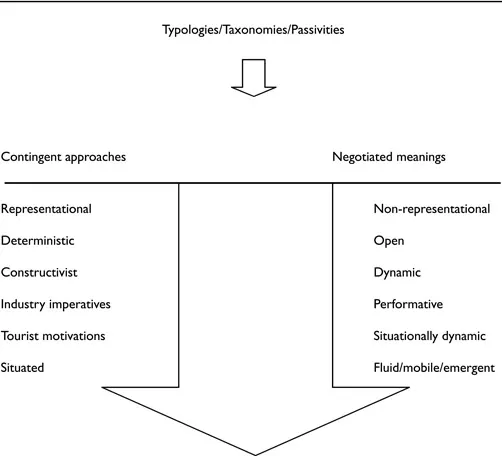

Our reflections have led us to a concern with context and the relationship between concepts of place, encounter and engagement, and with the way that theory works in supporting this structure. With this in mind we have turned to the discussions that took place during the planning of the book and the idea of situating it within the emerging and developing theoretical and conceptual influences that have appeared over the last decade and which have begun to underpin and position research in both heritage and tourism. Since the book itself is located at the intersection of heritage and tourism we agreed that it was worthwhile reflecting on how these developments might relate to the book as a whole and to the individual contributions of each chapter. In doing so it has become apparent to us that there is a duality in the emerging literature in heritage. As such, we have identified theories and conceptual approaches that are contingent on the way that both heritage and tourism are structured by representational narratives and that are negotiated in more open, non-representational and performative situations.

There is no attempt here to comparatively evaluate these distinct perspectives. We merely suggest that they exist, and that an understanding of them and their differences may help to circumscribe our debate and elucidate it in ways that provide insights that are theoretically informed. Our contingent approach, then, is based on conventional structuralist themes that identify sources of power and authority in the touristic nexus and examine the ways in which these are implicated in representational and discursive practices. Representation is a key cultural practice in the ‘giving and taking of meaning’ through discourse in the context of a circuit of cultural production and consumption (Hall 1997) and has found its clearest expression in heritage in the work of Smith (2006). Representation has also been discussed in the context of visual culture as a vital means of processing cultural production and recognised for heightening significance in touristic practices (Crouch and Lübbren 2003; Waterton and Watson 2010).

Studies may, therefore, be concerned with the politics of such practices or with the operational modalities to which they give rise. They provide opportunities for the deconstruction of practice and representation and the analysis of powerful discourses. They identify the deterministic aspects of power relations and seek to situate heritage tourism in wider debates about power, social structure and their sustaining narratives. They account for the political economy of heritage tourism, its national and touristic contexts, and its role as a resource bounded by a need for economic development precariously balanced by concerns for limits and sustainability.

Our negotiated approach is an attempt to capture meaning in different ways – methods that have come to be distinguished by a concern with the performative locus of tourism, the mobilities and fluidities that define moments of encounter and engagement, the nature of meaning as emergent in practice and embodied non- or pre-cognitive responses to experience. Broadly defined as non-representational theory and derived from recent thinking in cultural geography (Dewsbury 2003; Thrift 2007), it might be considered in opposition to representational theory or perhaps more usefully in contradistinction to it and more-than-representational in its effect (Lorimer 2005). We are inspired by Crouch’s (2002: 207) provocation: ‘Tourism is a practice and is made in the process. In making these claims I challenge familiar representations of tourism as product, destination, consumption’.

Table 1.1 is indicative of these relationships and recognises that the duality as it is presented here has emerged or ‘moved on’ from conventional analyses that have sought (fruitlessly, we believe) to taxonomise heritage, tourism and tourists and to represent them as passive recipients of tourism as it is constituted in its operational modalities.

While the purpose of this framework is to facilitate some theoretical coherence in moving the debates forwards in ways that respond to the concerns of the book, it is also recognised that such a variety of subject matter and approaches presents a considerable challenge in terms of developing common themes and perspectives. It is perhaps sufficient for the framework to provide an indicative range of theoretical bases from which our debate might be advanced. With this in mind the following considers in more detail the contexts and themes that frame our discussion.

Table 1.1 The conventional ‘heritage’ ‘tourism’ literature

Contexts

First we examine the central concerns of this book (place, encounter and engagement) as a series of contexts and moments where and when tourism, heritage and tourists converge. We use the word ‘tourist’ here as shorthand for people performing tourism in performative contexts, which seems to be an altogether more satisfactory way of describing this complex and puzzling activity, and which responds to Bærenholdt et al. (2004: 8–9) in recognising the physical and social fluidities involved. The word ‘tourism’, by the same calculus, is applied to that activity with distinct reservations about its ontological status. Such doubts are the natural consequence, first, of a mature phase in tourism studies (and are similar to the doubts that have long fuelled the so-called ‘heritage debate’) and, second, of the plurality of disciplines involved in its theorisation. While we do not intend here to attempt to stabilise the inherent conceptual wobble in either tourism or heritage, we are crucially interested in its consequences. These doubts open up for us a significant avenue of inquiry, one that is pursued in this book and that leads into some unexplored corners and intersections in the conceptual mapping of our subject.

Place is, of course, central to tourism studies. Tourism both makes places and transforms them, ofte...