eBook - ePub

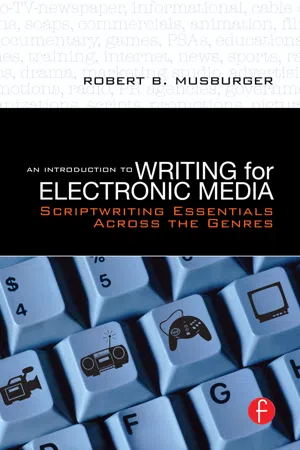

An Introduction to Writing for Electronic Media

Scriptwriting Essentials Across the Genres

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Introduction to Writing for Electronic Media

Scriptwriting Essentials Across the Genres

About this book

"Wonderfully practical....just what every media writer needs."

Christopher H. Sterling

George Washington University

* Learn what it takes to write for commercials, news, documentaries, corporate, educational, animation, games, the internet, and dramatic film & video productions

* Outlines the key skills needed for a successful media writing career

The demand for quality and knowledgeable multi-platform writing is always in high demand. An Introduction to Writing for Electronic Media presents a survey of the many types of electronic media you can write for, and explains how to do it.

Musburger focuses on the skills you need to write for animation versus radio or television news versus corporate training. Sample scripts help you learn by example while modeling your own scripts. Production files illustrate the integral role writers' play in the production process, and individual movie frames allow you compare these to the real scripts.

Armed with the skills developed in this book, a media writer can apply for a variety of positions in newsrooms, advertising firms, motion pictures or animation studios, as well as local and national cable operations.

Robert B. Musburger, Ph.D., is Professor Emeritus and former Director of the School of Communication, University of Houston, USA. He has worked for 20 years in professional broadcasting, serving as camera operator, director, producer, and writer. Musburger has received numerous awards for his video work and teaching and he continues to work in electronic media with his Seattle, WA,. consulting firm, Musburger Media Services.

"[An] authoritative and clearly written description of the processes involved in writing for film, radio and television production."

Raymond Fielding, Dean Emeritus

Florida State University

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Introduction to Writing for Electronic Media by Robert B. Musburger, PhD,Robert B. Musburger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Getting Started:

Loading the Application and Sharpening the Pencil

The wave of the future is coming, and there is no fighting it.

Introduction

Before you sit down to start writing any form of script for any medium, genre, or method of distribution, you need to consider the common factors that exist among all media forms, despite their basic differences. This chapter will reveal as many common traits as possible to avoid repeating the same information throughout the text from chapter to chapter. Such topics include correct English that is written to be read out loud, writing for an audience, and understanding the laws and censorship affecting writers. At the same time, you may need to recognize that there will be duplication and repetition of some material when the redundancy is critical for that particular type of writing.

Topics included in this chapter cover the history and types of scripts, accurate and concise English, language discrimination, law and censorship, and the audience and distribution.

Background

The written forms used to instruct a production crew to carry out the writer’s desires did not blossom forth overnight. Script formats evolved over many years through the development of a variety of entertainment venues. Even within a specific medium, variations of format style evolved as the technology of the medium changed to meet the combined needs of the production staff as well as the challenges of the latest technology.

Live theatrical performances presage all forms of modern media. You may learn much from the study of live theater in addition to recognizing the field of theatrical production as a predecessor of electronic media.

In the earliest time of live presentations by actors, the actor-director determined the story line, dialogue, and action. In many cases, nothing was written, but stories passed from one troupe to another or became simpler in the memory of the originator. When productions became more complex, notes were written and passed from one performing group to another. Finally, actors and directors wrote more detailed scripts to guarantee that a play would be performed as the writer had intended.

As the theater evolved, so did the scripts that the directors and actors followed. The format became relatively standardized so that whoever needed to read or follow the script would be able to understand what was expected of them as members of the cast or crew. The script was the bible for the director, listing all of the dialogue and who spoke the lines, as well as the basic settings and action. The director had the prerogative of making modifications as the rehearsal process moved forward. But, before rehearsals started, the actors needed the script to learn their lines and basic blocking movements, both of which could be modified by the director.

Before the end of the 19th century, motion pictures followed live theater in presenting dramatic productions, as well as documentaries and other genres as the field developed. The original filmscripts mimic the format layout of theatrical scripts once scripts became the rule in film. As with theater directors, early filmmakers shot film without recorded sync sound and so needed little in the way of a written script. The director/writer told the cinematographer where to place the camera, and the actors were told where to stand and move and what lines to mimic. As the camera rolled, the director yelled directions to the actors. Little postproduction was necessary since the early films often were shot in one or two long takes in the 10-minute-long scenes.

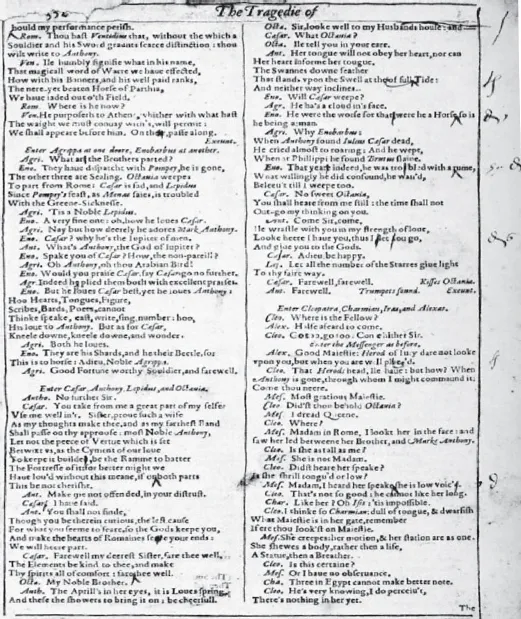

Figure 1.1. A typical Shakespearian era play script.

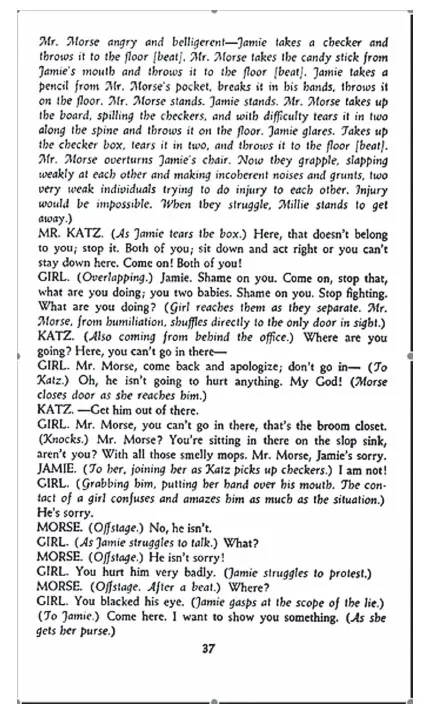

Figure 1.2. A script from a 20th-century play.

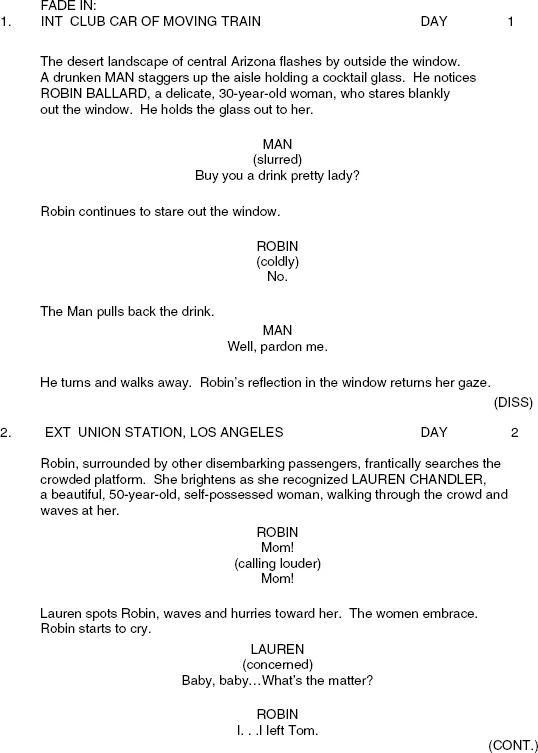

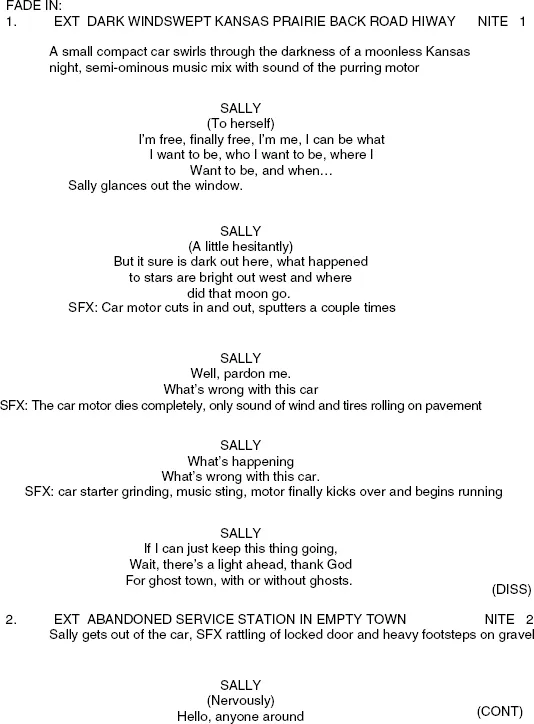

Figure 1.3. A modern film scene script.

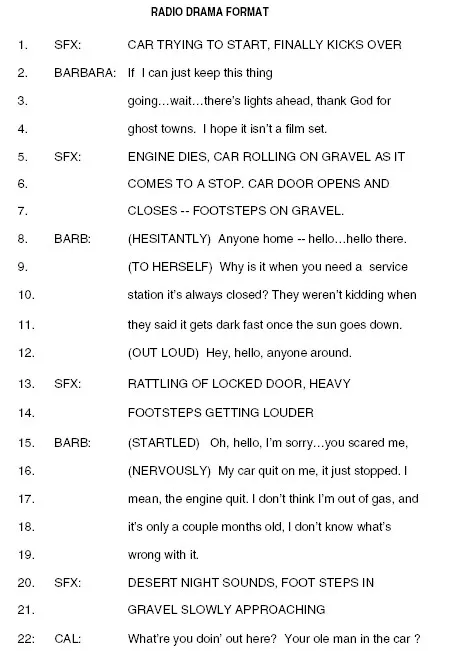

Figure 1.4. A typical radio drama script.

When sound arrived, filmscripts became reasonably standardized in a single-column format. In individual portions of the script, scene description, action, movement, dialogue, and the name of the actor were set, each with variations in margins. That made it easy for actors and crew to concentrate on the their parts of the script.

Shortly after the turn of the 20th century, radio became a reality for drama, news, and, of course, commercials. The first radio scripts resembled theater scripts, except instead of describing scenes and action, instructions for sound effects and music cues completed the script. Dialogue was much more detailed since radio drama is, in essence, a series of dialogues with music and sound effects helping to build the imagination factor. Radio’s advantage lies in requiring the audience to use its imaginations to fill in the visual gaps. This allows radio drama to achieve complicated effects that, until digital media arrived, were impossible to create in either film or video.

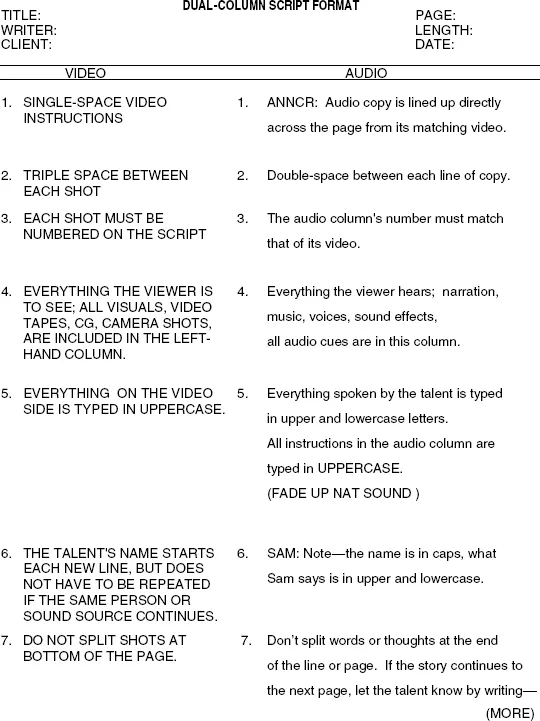

It became obvious early in the days of television that motion picture and radio script formats did not work well for live multiple-camera productions. A type of script developed for audio-video production at about the same time. The two-column format placed both sound and picture elements of the script on their own spaces in the script. This made it easier and more accurate for the cast, crew, and director to isolate the portion of the script critical to each. The left-hand column (at one time the networks NBC and CBS disagreed on the arrangement) now lists all visuals, with camera instructions, camera framing, shot selection, and transitions all entered in capital letters. The right-hand column lists all of the audio, including music, sound effects, and narration or dialogue. All copy to be read by the talent is entered in uppercase and lowercase letters, and all other instructions are in caps. This system developed to make it easier for talent to pick out their copy from all other instructions.

Some newscasters prefer to have their copy entered in all caps under the false belief that caps are easier to read on a prompting device. Readability studies indicate uppercase and lowercase copy on prompters prevents reading errors and helps readers add meaning to their delivery.

Most dramatic video productions are shot single-camera style, and some commercials and documentaries adapted the single-column script format. Since many of the writers and directors moved back and forth between shooting film and video productions, it became comfortable to use the same single-column format. The physical appearance of the format followed the same pattern as the film single-column format.

Figure 1.5. A dual-column video script.

Figure 1.6. A single-column video script.

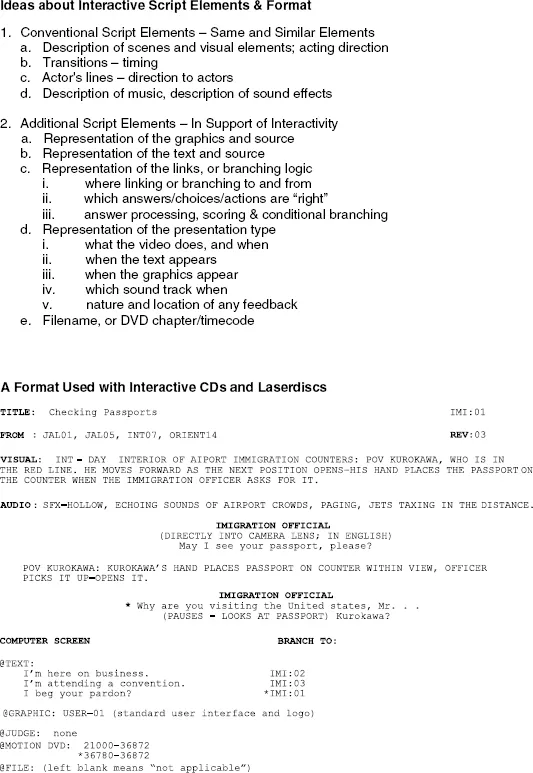

Figure 1.7. An interactive script.

Multimedia, Internet, and Web page scripts have not been formalized in the same way as scripts for other electronic media. Digital scripts take a variety of forms, some borrowing from both motion pictures and video as well as from audio-video script formats. The problem of indicating branching, choices for interaction, and the variety of different media used in one digital production requires a specialized script tailored to the specific production. The script must contain enough information for the producer/director to understand what is required to assemble the segments. The editor must also be instructed on the specifics of chapter assignments, transitions, linking, and other specialized techniques in a digital interactive production.

Script Variations

Today, television writers use both dual-column and single-column script formats, depending on whether the script will be produced as a live multi-camera production or as a single-camera video production. Each studio, station, or production operation may require a specific script format for its own operation. A writer should determine from the client how to format the script. Even with the two basic standard formats, there are many variations. Such variations depend on the size of the production, the budget, the production methods used, and the personal preferences of producers. Such variations also exist in film and audio scripts, but as modifications of the basic format. Interactive script formats have not yet reached a standard format, leaving a great deal of variations in the scripts used today.

Media Differences

Each of the electronic media requires that scripts provide information in different formats to best serve the people using the scripts. Radio scripts primarily serve the voices, secondarily served the director and, in some cases, a production operator. Therefore, a radio or sound script must accurately and precisely indicate the copy to be read, the music, the effects (if used), and timing factors. The writer must find a way to motivate the listeners so that the listeners visualize what they cannot see; the writer must prod their imaginations to feel what the writer is trying to convey using only sounds. For a writer, it is a daunting challenge, but at the same time, it is an opportunity to control the listeners by engaging their ears.

Filmscripts, like theatrical scripts, provide the basic blueprint of the production. The actors need to know their specific dialogue, and the director needs to have a written form of the overall concept that the writer’s vision provided in the script. Highly detailed and specific shots and framing are not necessarily required in a filmscript. Each key member of the production crew gains an understanding of the part his or her work will play in the production, but the final decision of specifics rests with the director.

Television and video scripts must balance serving both the aural and visual needs to be met by the script. The script must give the director all of the necessary information, including accurate narration, detailed (depending on the type of script) visuals, and timing information. Whether the script is single-column or dual-column, the same information must be easily read and obvious to the director. Talent will be most interested in the lines they need to memorize or read. The crew, in addition to their specific instructions from the director, will need to find their technical needs answered in the script. A writer is less responsible for technical matters in video scripts, providing instead general shot and transition descriptions and minimal audio instructions. But the video writer must concentrate on the visual without ignoring sound. A balance must be reached between using the tremendous power of visuals and, at the same time, stimulating the viewer’s hearing senses to match, contrast, or supplement the visual experience. The challenge for the visual writer demands that the balance between sight and sound make sense for the production and maximize the power of the medium.

Multimedia sc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Getting Started: Loading the Application and Sharpening the Pencil

- 2 Media Production for Writers

- 3 Spots: Public Service Announcements, Program Promotions, and Commercials

- 4 News

- 5 Documentaries

- 6 Informational Productions

- 7 Animation

- 8 Games

- 9 Drama

- 10 The Internet

- 11 Future

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Appeddix C

- Glossary

- Index