![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

There is now considerable precedent in European Law concerning the so called doctrine of “direct effect”.

The basis of the doctrine lies in the fundamental aspects of the Treaty of Rome and concerns the authority in Member States of treaty provisions and regulations, directives, decisions, recommendations and opinions coming from such provisions.

One important aspect of the doctrine is that responsibility for the implementation of European Law extends beyond governments to the national regulatory bodies themselves. The doctrine goes further in that it is argued that, even if implementation of European Law in a Member State by its government is deficient, the onus for the full and proper implementation of such law may still extend to regulators. Such deficiency may include incorrect as well as incomplete implementation and it is suggested that regulators may even find themselves liable for the payment of compensation if they fail to carry out their role correctly.

This monograph:

(1) examines the institutions and systems that are in place in the European Community with particular regard to those that effect the development and implementation of Community law;

(2) examines the development of the doctrine of “direct effect” and considers the importance of this to the agencies in England and Wales that are tasked with the control of discharges of dangerous substances into the aquatic environment; and

(3) examines the implementation, in England and Wales, of directives relating to the control of discharges of dangerous substances to water.

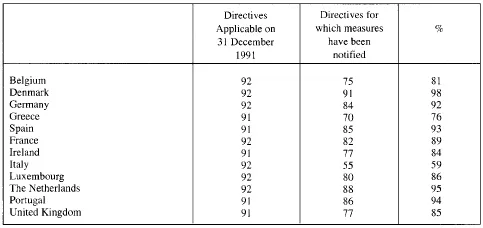

A consideration of the doctrine of direct effect would be of no significance if all Member States were fully and accurately to implement requirements of European Law into national law. Unfortunately this is not the case. Given below is a summary of a report prepared by the Commission of the European Communities in September 1992 on the level of implementation of directives relating to the environment. From this information it is clear that there is a considerable shortfall in the notification of implementing measures by Member States.

The report concluded that “the average success rate of 85% is quite good although delays in Italy and Greece give cause for concern.”1

Apart from the unfortunate fact that no Member State had at that time implemented all the directives as required, this figure in no way takes account of any incomplete or faulty implementation. It assumes that notification of action, by the Member State to the Commission, constitutes full and accurate translation of directive obligations into national law.

A report prepared for Directorate General XI by Environmental Resources Management Limited in December 1993 concludes “Our research has shown a very wide range in the rate and level of implementation of the directives.” [76/464 and its daughters]. “This reflects widely differing background conditions in Member States in terms of administrative legal systems and resources. The successful implementation of the requirements of Directive 76/464 and its daughter directives in all Member States still appears to be some way off and this fact needs to be explicitly addressed in any further policy developments in this area.”2

Implementation of environmental directives in the European Community.

It can be seen, therefore, that the issue of direct effect is one of real significance for all organisations with responsibility for regulating in any area covered by European Law.

As of 1 January 1994 the European Community ceased to exist, being replaced by the European Union. Most of the reference material used in this monograph pre-dates the formation of the European Union and as such the term “European Community” has been retained. References to the European Community should, where appropriate, be considered as references to the European Union.

![]()

2. METHODOLOGY

Much of the material on European case law reviewed in this monograph has been taken from European Court Reports (ECR) or Common Market Law Reports (CMLR). It is useful to consider the relevance of these sources in the reporting and recording of case law which subsequently provides us with precedent.

1. EUROPEAN COURT REPORTS

ECRs consist of:

(1) head notes which do not form part of the report;

(2) a review of the case by a judge rapporteur who is appointed by the court;

(3) the opinion of the Advocate General; and

(4) the decision of the Court.

The facts of the case are contained in the report by the judge rapporteur, but this is often not available for up to eighteen months after the case, or until such time as it has been translated into all the languages of the Member States.

The opinion of the Advocate General is based on a detailed review of the applicable case law. The decision of the Court will usually follow the opinion of the Advocate General, although in one case this did not happen and the Advocate General’s comments were contrary and regarded as a dissenting opinion3. Under these circumstances it is not clear what reliance should be placed on either the Court decision or the reasoned opinion of the Advocate General.

The decision of the Court is in two parts. The first part comprises the reasoning or motivation for the decision. The second part consists of the Court Order. The relevance of the first part in relation to the second is generally regarded as unclear when looking at these decisions for the purpose of determining precedent.4

2. COMMON MARKET LAW REPORTS

These are a good source of otherwise unreported, and therefore unavailable, cases but they are not to be regarded as official reports. It is found that on occasions there are significant differences between CMLRs and ECRs5. As such, and because of the unofficial nature of CMLRs, one may not be able to rely on their content for determining precedent.

3. THE ROLE OF CENTRAL GOVERNMENT

Discussion in this monograph on the role of government departments in the implementation of European law is based primarily on interviews that the author has undertaken with members and ex-members of the Department of the Environment.

4. THE ROLE OF THE REGULATORS

Interview techniques were also used to gain information on how the National Rivers Authority (NRA) and the privatised water companies see their role in regulating discharges of dangerous substances into the aquatic environment.

5. THE VIEW OF INDUSTRY

To explore industry’s perception of how the Dangerous Substances Directive6 has been implemented in England and Wales a standard letter was sent to the following trade associations:

Chemical Industries Association

International Wool Secretariat

Textile Finishers Association

Confederation of British Industry

Metal Finishing Association

![]()

3. THE INSTITUTIONS OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY

There are four main institutions of the European Community.

1. THE COMMISSION

The first institution is the Commission and this comprises the executive of the Community. It consists of independent appointees from the Member States, two from each of the five larger States, and one each from the seven others. It has responsibility for implementing the policy of the Community and to do this will draft proposals for legislation for the approval of the Council of Ministers. It also has responsibility for drawing up environmental action plans. By using information from Member States, on for example proposed national legislation, it will form a view as to whether community wide control in such areas is necessary.

Internally the Commission is divided into a number of separate directorates and it is Directorate General XI which has responsibility for environmental matters.

It is important when looking at the action of the Commission in the area of environmental protection to appreciate its original ambivalence toward environmental matters. One should remember that the original aim of the Commission was to remove barriers to free trade, with environmental protection measures being taken to avoid distortion within the internal market of the Economic Community. Such distortion could easily arise from disparate levels of environmental protection within the Member States. This ambivalence has to some extent been lessened by changes in the scope of the Community policies which now require the incorporation of environmental protection into its other areas of activity.

2. THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS

The second institution of the Community is the Council of Ministers, which is a political body consisting of one appointed minister from each Member State. The appointee will vary depending on the issue under consideration.

There are many Councils; two examples are the Council for Trade and Industry, and the Council for Arts. The Council which considers environmental matters meets twice each presidency and is made up of environmental ministers from each of the Member States. These ministers are usually supported by the permanent representative from the foreign embassy and at least one senior, technically qualified, civil servant.

Although the Council has as its objective the furtherance of Community policy, it is clearly influenced by national political bias and as such the Council’s voting procedure is crucial. As will be seen this voting procedure depends on which Treaty Article has been used for adoption of proposed legislation, there being two distinct systems.

The first is by unanimity of all the members of the Council.

The second is by qualified majority and involves a system of weighting whereby two of the larger States or five of the smaller States can be outvoted. This system allows environmental policy to be pushed forward more quickly and avoids the possibility of national veto by individual dissenting Member States. For example, the Directive on the control of large combustion plants was delayed for many years by the opposition of just two Member States7.

As a result of proposed changes to the current system of vote weighting, which would follow future expansion of the European Union, it will be even more difficult for Member States to veto proposed European legislation. However, it is important to include some democratic process of debate in any system that allows for the wishes of any individual Member State to be overruled. Such democratic input is provided by the next Community Institution, the European Parliament.

3. THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT

The European Parliament is made up of 567 MEPs who are directly elected every five years by the electorates of the twelve Member States. The Parliament acts primarily as a consultative body, although it also has some supervisory powers over the Commission with regard to the Community budget. It does, however, ensure that decision making in the Community retains a certain amount of openness, a necessary function in view of the fact that all the dialogue between the Commission and the Council of Ministers is carried out in secret. The “democratic” nature of the involvement of the Parliament has been particularly relevant since 1979 when simple appointments gave way to direct election of representatives.

The 1986 Single European Act also significantly changed the Parliament’s powers in relation to Community legislation. Under the “Cooperation Procedure”, as set out in Article 149 of the Treaty (as amended by the Single European Act), the Parliament now has powers to propose amendments to, or to reject, any proposed legislation that is the subject of qualified majority voting. If proposals are rejected by the Parliament the measures could then only be adopted by the Council by unanimity. Any amendments proposed by the Parliament must be considered by the Commission and, if as a result these are inserted in the proposed legislation, the Council must accept these by qualified majority, or adopt some other proposals by unanimity, or let the proposals lapse. Ball and Bell8 give an example of such a situation in relation to Directive 89/458 on Emissions from Small Cars, where the Parliament inserted a stricter test than was originally proposed by the Commission, or which was wanted by the majority of the Council. As a result of the Parliamentary consultation stage the Commission inserted the stricter test into its proposals. The Council as a result had a choice of agreeing to the proposals or not having any directive at all.

Because of the difference in the voting procedures, it is important whether a directive is adopted under Article 100a (qualified majority) or under Article 130s (unanimity). This question was addressed in the case of Commission v Council9, which concerned the Directive on waste from the titanium dioxide industry. In this case the Council consider...