- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Challenge of the Able Child

About this book

First Published in 1997. Many able children are underachieving in schools because teacher and parents are failing to identify and therefore adequately provide for their special needs. This second, updated edition of Challenge of the Able Child will assist teachers in becoming more patient and observant in the classroom so that they can accurately define their objectives in providing for these children. Above all, this book aims to help teachers and parents discover the excitement, challenge and pleasure of teaching able children and helping them achieve their potential. The education of able children has moved on considerably since the first edition and this is reflected in the text with update and additions in computer technology, new resources and an expanded bibliography.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Challenge of the Able Child by David George in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

What's in a Name?

The gifted and talented come in a tremendous variety of shapes and sizes and are clearly not a homogeneous group. (Harry Passow)

Who are we talking about? Definitions abound and create much confusion. Anyone who takes the trouble to delve into the mass of published material on this subject is likely to be startled, if not confused, by the variety of terms used to describe very able children and the various criteria used to define them. Yet defining ‘gifted’ and ‘talented’ is an extremely important matter and surprisingly complicated. Many people still discuss giftedness or talent as if they constitute a syndrome or a set of recognisable characteristics. These are best seen as umbrella terms for individuals with a wide variety of special abilities. In some areas we hesitate to use the words ‘gifted’ and ‘talented’, but we shall do so because current English usage does not use these terms in the Biblical sense. Indeed, the parable of the talents in the New Testament is a very sad story because the third person buried his talents, so here was our first underachiever! The gifted are certainly not a homogeneous group and the search for general characteristics of giftedness has not been fruitful, except where a restricted definition has been used. I would suggest that we seek out what represents gifted behaviour in the fields of human endeavour in which we are interested, describe under what conditions such behaviour will emerge and identify ways of developing such behaviour. This will help us get away from pseudo-scientific labelling of children. But, for teachers, the term ‘intellectually underserved’ has some value. It indicates that the targets of our concern are those who have special learning abilities that have not been matched with an appropriate programme. Thus the identification process involves the study of not only the child's learning characteristics but also the learning environment.

To some people the concept of giftedness means the skills of an outstanding athlete, artist or musician, while for others it encompasses the work of a promising mathematician, scientist, writer or poet. Its application to levels of achievement may also vary from ‘above average’ to ‘outstanding’. What is required is a working definition which can serve two purposes: provide an agreed statement to facilitate discussion and enable a positive response to anyone requiring further clarification of their ideas of exceptional ability. A clear working definition must lie between the two extremes, being neither too specific – it should not be so narrowly conceived that some children of exceptional ability are excluded, nor so broad and that no clear guidance is given.

The particular definition adopted by a school in its policy for gifted and talented children is vitally important because it will determine who is selected for any special programme. Further, there is a danger that one's definition and consequent identification methods will discriminate against such special populations as the poor, minority groups, the disabled underachievers and even some female students.

Renzulli et al. (1981) noted that a definition of giftedness must

(1) be based on research about characteristics of gifted children;

(2) provide guidance in the identification process;

(3) give direction and be logically related to programming practices;

(4) be capable of generating research that would test the validity of the definition.

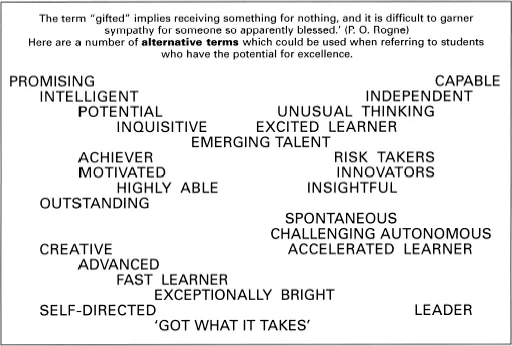

The following terms are just some that I have encountered: ‘able’, ‘more able’, ‘exceptional’, ‘talented’, ‘superior’, ‘gifted’, ‘higher educational potentials’, ‘more receptive learners’, ‘more capable learners’ and ‘higher academic potentials’. These terms may or may not refer to the same or similar groups of children. There are obvious dangers in making generalisations about any group of people and this is no less true when talking about very able children.

These observations suggest that, although the notion of the gifted and talented child has been generally recognised, the need for a more exact definition is a new phenomenon in our educational system. But why has it taken so long to realise this need even when society recognises the general notion of the gifted?

One can respond by citing the following reasons. Firstly, identifying the gifted child through performance of the given task was sufficient. The educational system itself was felt to be good enough to identify the gifted. That is to say, nobody was interested in discovering the gifted children in the early stages of their education. Secondly, there seems to be a cultural factor in the sense that to be gifted is to be different, and the idea of an individual being different from the others within society should not be encouraged. Having made these observations, it is fair to want to know what has prompted the sudden urge to have more precise definitions of the gifted child. Our society has come to realise the importance of having a deeper understanding of gifted children and, if possible, of identifying their essential characteristics.

This new interest has been influenced by the following factors, among others. Firstly, psychologists have become increasingly interested in the functioning of the human mind. In their efforts to understand how the mind works, these professionals have discovered that some individuals are endowed with very little potential to perform certain tasks which most average children find rather easy to perform. Psychologists identified these children as needing to be treated differently from average children, but some felt it would be unfair to assess the intellectual performance of intellectually abnormal children even when we realise that the intellectual potential in the two groups is quite different. Nevertheless, there followed the establishment of special educational institutions, and specialist teachers and a great deal of money were provided to support this work. It is now a legal requirement to support children who are disabled, whether emotionally, physically or intellectually. Later it was realised that by concentrating on the needs of disabled children, educators were dealing with only one end of the normal distribution curve of children's ability. The other end of the spectrum consisted of those children who seemed to be endowed with performance potential that was over and above that possessed by the average child.

Secondly, education has been recognised as an inalienable right for all individuals. Consequently, governments are expected to make sure that both the normal and the abnormal are presented with the most relevant education. This also calls for the most appropriate method of teaching these important but different groups of individuals.

Thirdly, in our modern societies certain specialised services are identified from time to time. These services may, for example, require people with very high intellectual abilities. In such circumstances, society has a duty to identify those individuals who are endowed with the requisite abilities. A case in point is that some countries have now established educational institutions for students with high potential in science and mathematics (to help in international competition in space programmes) and sport (international sporting events).

Fourthly, the belief that education is an inalienable right implies that the cost of running schools is very high for any government. It has also been discovered that children with more than normal potential ability take a shorter time to learn certain tasks than average and disabled children. If governments are able to identify children with higher than normal potential abilities, they may end up spending less money on them.

Fifthly, some social scientists have discovered that children will engage in antisocial behaviour for lack of anything better to do. These are children who, because of their high potential ability, take a shorter time to accomplish certain tasks than the average child. In a classroom situation, such children may resort to making mischief because they are often idle for some of the time. Thus, it will be important to identify these types of children in order to reduce anti-social behaviour in our school systems and in society at large.

Sixthly, scholars are interested to understand the nature of human beings, and particularly to establish the limits of their intellectual potential.

Finally, educationalists are agreed that it is every child's right to go as far and as fast as possible along every dimension of the school curriculum in order to reach their considerable potential, and that this is one of the major aims of education.

Now, if the reasons cited above can stand the test of time, then an attempt should be made to offer an appropriate definition of the gifted child. It is clear that one cannot identify a single purpose as the motivation for wanting to define terms. However, for every definition, some purposes are more pronounced than others. Thus, for this book, my main interest is to attempt to reduce the vagueness inherent in the term ‘giftedness’ as it is commonly used. If I register any measure of success towards this end, then I hope it will be of some use to teachers and parents, as well as to social workers, policy makers and researchers as they deliberate about the gifted and talented individuals in our society.

Discussion on the precise definition of gifted and talented children should begin rather humbly by examining some versions of the term ‘gifted’ advanced by scholars and other interested groups, led by Plato (The Republic). In his attempt to find a lasting solution regarding the best government in his Athenian city-state, Plato indicated that in any community there are three groups of people: the craftsmen, the civil servants and the philosophers. His classification was based on the potential endowment of intellectual abilities each class enjoyed. While the craftsmen were least endowed with intellectual abilities, the philosophers possessed the most. Plato then prescribed a system of education which would help to sort out who belonged to each group. Thus most people would drop out of the education system and only a small group would reach the apex. This small group consisted of individuals who were the best at handling dialectics, one of the most abstract and intellectually demanding subjects offered in the Athenian educational system of that day. It was from this small group that the king was to come.

Even if Plato never talked about ‘the gifted’ as such, it is plausible to infer the notion from the above general observations. If this is granted then one is likely to draw out certain features from the notion of giftedness adopted by Plato. Firstly, the gifted individual exhibits superior intellectual abilities. Secondly, the human abilities considered as gifts are also useful in the service of society in general. Thirdly, only a small percentage of the entire community is endowed with a particular gift. Finally, the potential gift is within an individual from birth, waiting to be developed.

The next definition of the gifted individual to be considered is given by Painter (1980), who states that

The capabilities which go to make up giftedness are not absolute for all types of societies and stages of economic development. Those qualities which will be considered to represent ‘gifts’, even if that particular word is not used, will be the abilities which enable individuals to perform those functions which are the most highly prized in their respective communities or who are able to produce the type of artefact in great demand.

The quotation reinforces the observation made about Plato that giftedness refers to those superior abilities considered to be most worthwhile in the eyes of the community concerned. However, whereas Painter would consider any human ability as potentially a gift, Plato would so consider only intellectual abilities. It is also important to note the new feature in Painter's definition: that the values and priorities of a particular society will dictate which abilities are to be valued as ‘gifts’ within that society.

In a definition by Newland (1976) a gifted or talented child is one who shows consistent remarkable performance in any endeavour. This definition is consonant with the previous two, regarding as central the place that superior abilities and their usefulness enjoyed in the meaning of giftedness. But two rather subtle notions are floated here – that the superior abilities be demonstrated in the performance of the individual considered as gifted and, above that, that the superior performance be consistent in the particular individual. This caveat excludes from the definition those examples of exceptional achievement that occur by chance or in isolation. For example, the student who manages to be top of his or her class in a physics examination by scoring 90 per cent is not to be considered gifted just on the strength of this one particular performance.

Two more definitions of the gifted may be noted. On the one hand, a gift is said to imply something that is freely given and that, as a present, may be expected to be beneficial to the recipient (Painter, 1980). On the other hand, giftedness is said to be our own invention rather than something we discover; that it is what one society or another wants it to be and hence its conceptualisation can change over time and space (Sternberg and Davidson, 1986). Note that the first of the two definitions does add a new feature to the meaning of giftedness: that what is considered a gift should be of some worth from the perspective of the individual involved. However, what might concern a careful observer is the seemingly antagonistic stance that each of the above definitions takes regarding the origin of what is considered as a gift in an individual. Thus, whereas one definition emphasises that gifts are freely given to an individual (Plato concurs in this), the other stresses that gifts can be regarded as human contrivances. How do we get ourselves out of this difficulty?

It seems to me that rather than the two definitions conflicting over the origin of talent, they each constitute distinct, but not inconsistent, features within an overall definition. Thus, one stresses that human abilities that are considered as gifts are bestowed upon individuals freely and naturally. The other, however, stresses the fact that the decision as to which abilities qualify as gifts falls squarely on the students themselves. In a nutshell, although we are not the originators of human potential abilities, whatever abilities are developed and eventually qualify as human gifts depend strictly on human decisions. These crucial decisions will of course be influenced by which talents are currently in demand in a particular society. In addition, they are greatly influenced by teachers, parents and the ethos of schools.

There is yet another type of definition of the gifted which seems to be rather different from those discussed above. According to psychologists, the gifted are considered to be those two hundred superior individuals in a thousand in a given ability; the extremely gifted are those ten superior individuals out of a thousand in a given ability; and the genius as the one top individual in a thousand in a given ability. This definition emphasises certain features that are also noted in one way or another in definitions cited earlier. For example, giftedness involves any human ability, be it intellectual, physical or moral, and regardless of whether it is useful or not. However, the definition does highlight the fact that a superiority involving a single ability would qualify an individual to be regarded as gifted.

From the discussion so far, the following features have emerged as possible contributions to a definition of giftedness:

- superior human abilities;

- superior intellectual abilities;

- natural human abilities;

- superior potential human abilities;

- superior human performance;

- consistent superior human performance;

- an intelligence quotient above 100 per cent;

- placement in the top two hundred in a homogeneous group of one thousand students.

The greatest challenge now is to find out which of the above features can be considered as legitimate in a definition of giftedness and which we cannot accept, especially when some contradictions seem implied.

A quick perusal of the features listed suggests some agreement as to what is central in a definition of a gifted individual. For instance, there seems to be common agreement that natural supe...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 What's in a Name?

- 2 The Characteristics of Gifted and Talented Children

- 3 Identification

- 4 Provision and Strategies for Teaching

- 5 Enriching the Curriculum

- 6 The Parent/Child/Teacher Model

- 7 Resources and Policies

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index