- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Market-Driven Thinking

About this book

Market-Driven Thinking provides a useful mental model and tools for learning about how executives and customers think within marketplace contexts. When the need to learn about how executives and customer think is recognized, a solution is usually implemented automatically, with no thought given to the relative worth of alternative methods to learn fill the need. Thus, the "dominant logics" (most often implemented methods) to learn about thinking are written surveys and focus group interviews--two research methods that that almost always fail to provide valid and useful answers on how and why executives and customers think the way they do.

Through descriptive research, MDT examines the actual thinking and actions by executives and customers related to making marketplace decisions. The book aims to achieve three objectives:

* Increase the reader's knowledge of the unconscious and conscious thinking processes of participants marketplace contexts

* Provide research tools useful for revealing the unconscious and conscious thinking processes of executives and customers

* Provide in-depth examples of these research tools in both business-to-business and business-to-consumer contexts

This book asks how we actually go about thinking, examining this process and its influences within the context of B2B and B2C marketplaces in developed nations.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

A Primer in Learning Market-Driven Thinking

I

Thinking, Deciding, and Acting by Executives and Customers

Synopsis

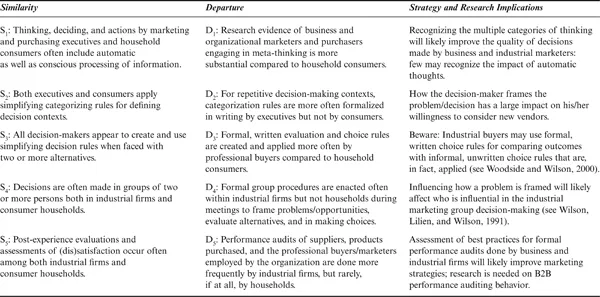

Both marketing executives and consumers engage in a combination of automatic and strategic (i.e., controlled) thinking and doing processes when they become aware of problems and opportunities. Similarities and departures in these processes among executives and consumers occur through all stages of their decisions. This chapter includes a paradigm describing similarities (Si) and departures (Di) in the stream of thinking and behaviors of executives and consumers. For example, both executives and consumers apply simplifying categorizing rules for defining decision contexts; for repetitive decision-making contexts, categorization rules are more often formalized in writing by executives but not by consumers. The literature on the quality of decision processes offers several easy-to-apply, but often unknown, rules helpful for both executives and consumers for improving the quality of their decisions. These rules are examined briefly within the framework of similarities and departures. Formal study by business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) marketers of such similarities and departures of consumer/business buying decisions may be helpful for recognizing nuances critical in selling–buying processes for achieving desired outcomes—such as getting a sale or building a marketing relationship.

Introduction: Achieving a Deep Understanding of What’s Happening

Examining similarities and departures in the thinking processes among executives and consumers helps to achieve more useful “sensemaking” (Weick, 1995) of real-life decision-making. For example, research on executive and consumer decision processes includes modeling the implicit thinking and deciding processes by decision-makers. What we’ve learned from such research: even when B2B marketers and consumers report following explicit rules for searching and making choices, thick descriptions of what happens in real life do not support their reports (see Woodside, 1992). Automatic thinking, rather than explicit (or “strategic”) thinking (see Bargh, 1994), appears throughout most phases of decision-making, and often the decision-makers are unaware of how such unintended thoughts are influencing their choices.

Why is the direct research logic particularly valuable for studying executive and consumer decision processes? Part of the answer lies in the work by Gilovich (1991). He identifies overconfidence in our individual perceptions of reality as likely to be the single greatest shortcoming to improved knowing. The human tendency is very strong to believe we know even though what we know “isn’t so” (Gilovich, 1991). Thus, answers to closed-ended questions by executives or consumers in a mail survey fail to account for what is reported by these decision-makers that just isn’t so, as well as what they fail to report that is so. Because direct research often combines the collection of supporting documents, confirmation of thoughts from multiple interviewing of multiple respondents, and direct observation of some interactions of people participating in the processes, direct research studies increase the quality of data reported compared to one-shot survey-based studies.

It is useful to consider whether executives and consumers exhibit similarities or differences in their decision-making. Critical nuances in conversations, thought processes, and behaviors associated with individual business and consumer case studies support the view that every decision process is unique (see Woodside, 1996). Yet a compelling need to categorize and simplify exists in both theory and management practice that results in grouping cases into a manageable number of processes. Effective thinking requires building and comparing typologies and categories. For example, associating unique decision processes with executive versus consumer problem-solving implies two process categories that differ significantly.

This compelling need is to achieve a deep understanding of what is happening, what outcomes are likely to occur or not occur, and the reasoning (i.e., the implicit “mental models” being implemented by the decision-makers; see Senge, 1990) supporting the observed decision processes. This chapter does not offer an in-depth review of this literature, but it does describe specific similarities and departures between executive and consumer decision processes. Crafting such propositions provides useful ground for context-based models that describe the contingencies resulting in observed similarities and departures. By the end of the discussion, the thesis presented here reaches two central conclusions:

- it is useful to describe and test noteworthy similarities in executive and consumer decision processes, to achieve greater sensemaking of both processes;

- for every similarity proposition, stating a relevant departure proposition may be supportable empirically.

Consequently, the study of similarities and departures in such decision processes presents multiple meanings and cues. The answer most useful in the principle issue is that both similarities and departures should be expected in studies of thoughts, decisions, and behaviors among executives and consumers.

Using “direct research” (Mintzberg, 1979) to examine similarities and differences in the decision processes of executives and consumers helps fulfill a compelling need for deep understanding. Direct research compels explicit model building when studying the nuances behind the similarities and differences—and how both the executive and the consumer might improve their thinking processes. Direct research includes face-to-face interviews with decision-makers—usually multiple interviews of the same persons in two or more sessions and/or interviews with additional persons mentioned during initial interviews. Direct research of decision-making attempts to capture deep knowledge of the streams of thinking and actions of “emergent strategies” (Mintzberg, 1979). Such emergent strategies include the nuances arising from transforming planning with implementing decisions/actions, including adjustments in thinking, searching for information, modifications to decision rules, last-minute third-party influences, and unexpected contextual influences. Mintzberg (1979) provides seven basic themes for direct research:

- The research is as purely descriptive as the researcher is able to make it.

- The research relies on simple—in a sense, inelegant— methodologies.

- The research is as purely inductive as possible.

- The research is systematic in nature—specific kinds of data are collected systematically.

- The research, in its intensive nature, ensures that systematic data are supported by anecdotal data because theory building seems to require description, the richness that comes from anecdote.

- The research seeks to synthesize, to integrate diverse elements into configurations of ideal or pure types.

Because direct research runs counter to the dominant logic of empirical positivism (i.e., surveys or experiments that test deductively developed hypotheses), it may be surprising to learn that a substantial body of literature is available in organizational marketing and consumer research that uses direct research methods. Direct research examples in organizational marketing include the following studies:

- Based on data from direct research, Morgenroth (1964) and Howard and Morgenroth (1968) developed binary flow diagrams and a computer program that accurately predicts distribution-pricing decisions by Gulf Oil executives.

- Howard et al. (1975) reviewed a series of organizational marketing studies employing direct research—which they label “decision systems analysis” (DSA).

- Montgomery (1975) showed the stream of thoughts (including heuristics and decisions) within one supermarket’s executive buying committee through their deliberations on whether to buy new grocery products.

- Woodside (1992) included in-depth reports of ten field direct-research studies conducted in Europe and North America by a team of academic researchers.

- Woodside and Wilson (2000) showed what-if decision trees based on “thick descriptions” of marketers’ and buyers’ decision processes involved in the same B2B relationships.

Direct research examples in consumer research include the following studies:

- Cox (1967) conducted face-to-face interviews with two housewives separately each week for twenty weeks to gain deep understanding of their automatic and implicit thoughts related to grocery purchases.

- Bettman’s (1970) doctoral dissertation employed direct research to learn the heuristics implemented by two housewives when deciding what to place in their supermarket shopping carts.

- Woodside and Fleck (1979) twice interviewed two beer drinkers separately in their homes—each of the four interviews lasted three hours—to learn their thoughts, feelings, and actions regarding beer as a beverage category, brand preferences, product/brand purchase decisions, and beer consumption decisions.

- Payne et al. (1993) compared and contrasted findings from consumer field and laboratory studies employing direct research methods.

- Fournier (1998) employed direct research to learn how brands relate to how consumers come to understand themselves.

Direct research often includes two or more face-to-face interviews with the same respondents spaced over weeks or months. The use of such a method allows respondents to reflect on their answers given in earlier interviews. Because reflection clarifies and deepens understanding (see Weick, 1995), respondents often provide deeper insights into the reasons for their decisions and actions than expressed earlier. Multiple interviews with the same respondents permit these respondents to learn what they really believe and feel related to the topics covered in the study. Weick (1979, p. 5) captures this point well when discussing the criticality of retrospection: “How can I know what I think until I see what I say?”

The Fallacy of Centrality

Closely related to the principle of overconfidence is the “fallacy of centrality” (i.e., experts underestimating the likelihood of an event because they would surely know about the phenomenon if it actually were taking place; see Westrum, 1982, and Weick, 1995). “This fallacy is all the more damaging in that it not only discourages curiosity on the part of the person making it but also frequently creates in him/her an antagonistic stance toward the events in question” (Westrum, 1982, p. 393).

Consequently, thinking we know the answer to the issue of whether executives and consumers match or differ in their decision processes is likely to be a false premise. To overcome the overconfidence bias and the fallacy of centrality, data and information from field studies are needed on the decision processes enacted by executives and consumers. Fortunately, field studies are available in the literature for both consumer and executive decision processes (e.g., Payne et al., 1993; Woodside, 1992).

These field studies provide findings and conclusions about how decisions are framed and made by consumers and executives. Consequently, rudimentary comparisons of similarities and differences in the decisions implemented by consumers and executives can be compared. Such comparisons are rudimentary because the studies reported were not done with such comparisons in mind; and usually differing research methods were used for collecting data in the studies. Striking similarities and differences can still be noted in these studies.

Thinking Similarities

Striking similarities include the following core observations. Both executives and consumers apply very limited (low-cognitive-effort) search strategies to frame decision contexts, to find solutions, and to create rules for deciding. Simon’s (1957) principle of “satisficing” rather than maximizing applies frequently in decision-making by executives and consumers.

Both executives and consumers frequently create and implement non-compensatory, rather than compensatory, heuristics for both identifying candidate solutions and making final choice decisions. Even when they report use of compensatory rules, careful analysis of the implemented decisions indicates that they didn’t use those rules.

Automatic mental processes (see Bargh, 1994), rather than strategic thinking, tend to occur in all phases of decision-making by both executives and consumers. Neither executives nor consumers often explicitly consider alternative ways of framing and solving problems.

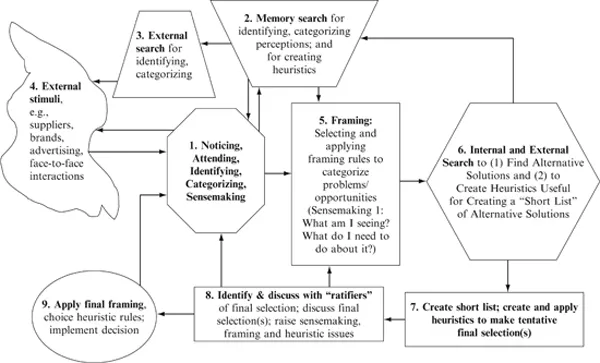

For major decisions, looping of thoughts back and forth to memory and thinking about external stimuli occurs frequently during decision-making. For example, consider “new task” problems by executives or “extensive problem-solving” situations by consumers. Such feedback loops are depicted in Figure 1–1 by left-to-right arrows. Mintzberg (1979) in particular emphasizes that feedback loops are often found in the decisions implemented by executives.

Figure 1.1 Decision process by executives and consumers.

Both executives and consumers frequently consult and seek approval from others before making a final decision (see Box 8 in Figure 1–1).

Several differences in decision-making between executives and consumers can be identified in the cited literature. Here are some noteworthy examples:

- Formal, written rules for searching for suppliers and evaluating vendor proposals are created for many categories of decisions within organizations but rarely by consumers.

- Formal performance audits by external audit professionals occur annually for purchasing and in many marketing organizations, but rarely are such audits done for consumer decisions.

- For many categories of decisions, documentation of deliberations and decision outcomes are more extensive in business organizations than in consumer households.

Five formal propositions of similarities and differences are described in separate sections following this introduction; these five propositions are summarized in Figure 1–2. The discussion closes with possibilities of the propositions for improving sensemaking to help plan and implement decisions that achieve desired outcomes.

Figure 1.2 Exhibit of executive and consumer decision processes: similarities, departures, and strategy implications.

S1: Automatic and Controlled Thinking; D1: Meta-Thinking

Bargh (1989, 1994) and Bargh et al. (1996) empirically support the proposition that most thinking, deciding, and doing processes include combining bits and pieces of automatic and conscious processes. Consequently, all decision-makers can only partly report the motivations and steps taken in their thoug...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I: A Primer in Learning Market-Driven Thinking

- Part II: Tools for Illuminating the Unconscious and Conscious Mind

- Part III: Customer Associate-to-Vendor (Store) Retrieval Research

- Part IV: Case-Based Research for Learning Gestalt Thinking/Doing Processes

- Part V: Learning How Initial Behavior Affects Future Behavior

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Market-Driven Thinking by Arch G. Woodside in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.