![]()

![]()

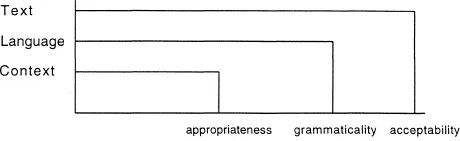

The process of discourse draws on context and language to create text. Part I is concerned with that process. More specifically, however, it is concerned with the acceptability of text, because a text cannot be said to exist for the person who reads or hears it unless that person accepts it as such. Within every culture certain standards of text, whether spoken or written, are considered by the majority of hearers or readers to be “acceptable,” whereas other standards, by contrast, are considered “unacceptable.” What constitutes acceptable or unacceptable text to an interpreter is, to a large extent, controlled by the language of the text as well as by the context in which the text appears.

Acceptability is a function of appropriateness and grammaticality. The first of these, appropriateness, is determined primarily by cultural and situational factors. It might be called “context acceptability.” As de Beaugrande and Dressler (1981, p. 11) put it, “The appropriateness of a text is the agreement between its setting and the ways in which the standards of textuality are upheld.” For a text to be judged appropriate, it must reflect basic values of the culture without violating any such values. It must also reflect the situation that gives rise to it. These are the contextual issues of discourse, and they are dealt with in various ways in chapter 1.

The other ingredient of acceptability, grammaticality, is a measure of language usage. It might be called “language acceptability.” If a text is judged grammatical, this is the same as saying that most readers or listeners accept the language of the text and find no serious fault in it. Just as there is a grammar of the sentence, there is also a grammar of discourse, governing discourse language. Chapter 2 examines discourse language and discourse grammaticality.

FIG. 1.1. Relationship between acceptability and discourse.

Different degrees of acceptability or unacceptability result from combining different degrees of appropriateness or inappropriateness with different degrees of grammaticality or ungrammaticality. When perceived by the reader or hearer of a text, these varying combinations translate into judgments of relative acceptability or lack of acceptability. The relation between the concepts of acceptability and text may be diagramed as in Fig. 1.1. Figure 1.1 shows that text is a product of context and language in much the same way as acceptability is a product of grammaticality and appropriateness.

The context of the discourse results in specifications for an appropriate form of the text. This form is known as the genre; chapter 1 is concerned with the elements that specify the genre. The genre, in turn, specifies a certain kind of language acceptability, or grammaticality. This is the register of the text. When the genre and register are matched in a way that is most effective for the intended purpose, the resulting text is likely to be considered highly acceptable. Chapter 2 is concerned with the elements of discourse language and with the way in which acceptable language can be matched with acceptable form to produce acceptable and effective texts.

![]()

1

THE CONTEXT OF DISCOURSE

What is the source of meaning of a text? How do people know how to interpret the words and nonverbal elements of a text? The answer is that every text comes along with another text that contains the key to its interpretation. This accompanying text—the CONtext— has its roots in the culture and the situation, including the interpersonal and intertextual relationships that gave rise to it.

At its most general level, the context is the culture. How people in their societies view the world and their place in it is a crucial part of understanding the texts they create. Unfortunately, very little is known about the relationship of language to culture. It is not possible to make accurate predictions about language based on knowledge of a specific culture. However, people’s attention can be drawn to connections between language and culture, and guidelines for understanding cultural context and the effect it has on the form and content of texts can be given.

Within any culture, it is possible to describe situations that give rise to texts. It is easier to see the role of language within situational contexts than within cultural ones. For example, language may reflect location through prepositional phrases. Also, certain types of functional language may be appropriate to a given situation. The elements of the situational context discussed in this chapter closely follow the analytical framework devised by Biber (1994). Although there have been many descriptions of situation, Biber’s is the only one that allows a true classification by restricting the variations in each element. It is, therefore, the only situational framework that can uniquely specify a genre.

Within its contexts, a text is simultaneously process and product. It is created out of the mutual interaction of producer and interpreter(s). At each stage in its production and interpretation, unspoken reference is made to the contexts that provide the environment for its development. Text and context continually feed each other. No text—written, spoken, signed, or otherwise communicated—is ever devoid of context.

The different components of context relate in predictable ways to discourse and text. Specifically, they give rise to the genre, which is the form of the text appropriate to its particular purpose within the situation.

CULTURE

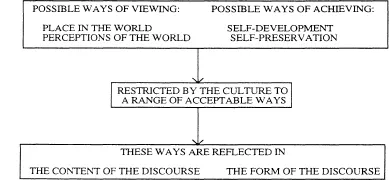

In any society, culture, in its most general sense, is concerned with individuals in a group. It has four main functions: It determines the various ways open to the individual within the group to develop the self, and hence the group as well. It specifies means for self-preservation. It determines the individual’s place within the group. And, it determines the individual’s and the group’s perception of the world. The specific culture of the group restricts each of these cultural attributes to a range of values or possibilities deemed acceptable to the members of that culture. Thus, the ways in which an individual can achieve self-fulfillment or perceive the world within a given society are limited by that society’s cultural norms and practices.

The relation between culture and discourse may be shown diagrammatically as in Fig 1.1. Place in the world, perceptions of the world, self-development, and self-preservation combine to provide the cultural context of discourse. Out of the cultural context arise, among others, discourses concerned with ethnicity and solidarity, power and exploitation, prejudice, sexism, ideology, and territory and time. Every text is based in a context of culture.

To function as members of a culture, speakers must have a high degree of communicative competence. They must know how to speak appropriately in given situations: what degree of respect is appropriate, what markers of politeness are required, what rules governing turn-taking are in force, and much more. In some cultures, qualities of voice (such as breathy or clear), volume, contour, tempo, and pitch may carry important cultural meanings such as degree of status, whether a person is acting as a petitioner or a patron, and which role in the situation the speaker is assuming. Gestures, postures, and facial expressions (to be discussed in detail later) may also play an important role in cultural communication. All of these comprise a culture’s styles of speaking, and these styles of speaking may be so important in a given culture that they may continue to exist long after the language itself has died out. An example of this is the Ngoni of southern Africa, who continue to use Ngoni styles of speaking even though they have lost their original Ngoni language.

FIG. 1.1. The relationship between culture and discourse.

The individual’s linguistic and cultural development, while making intracultural communication possible, can severely impede cross-cultural communication. Problems in cross-cultural communication have become an increasingly important concern in a world where economic and political decisions have international consequences. Wierzbicka (1991), summarizing a number of recent investigations into cross-cultural communication, listed the following four points as the main ideas emerging from these studies:

1. In different societies, and different communities, people speak differently.

2. These differences in ways of speaking are profound and systematic.

3. These differences reflect different cultural values, or at least different hierarchies of values.

4. Different ways of speaking, different communicative styles, can be explained and made sense of, in terms of independently established different cultural values and cultural priorities.

To take one example of different cultural attitudes toward speaking, consider Wierzbicka’s analysis of “self-assertion” as expressed in Black American culture, White Anglo-American culture, and Japanese culture:

Black American culture

I want/think/feel something now

I want to say it (“self-assertion,” “self-expression”)

I want to say it now (“spontaneity”)

White Anglo-American culture

I want/think/feel something

I want to say it (“self-assertion,” “self-expression”)

I cannot say it now

because someone else is saying something now (“autonomy,” “turn-taking”)

Japanese culture

I can’t say: I want/I think/I feel something

someone could feel something bad because of this

if I want to say something

I have to think about it before I say it

In these descriptions, spontaneity, an important value in Black American culture, is in conflict with autonomy and turn-taking, crucial to White Anglo-American culture. Both of these values conflict with the value the Japanese place on not saying anything that would embarrass or hurt the feelings of another person. Imagine individuals from these three cultures attempting to hold a conversation, in which the Black American would spontaneously interrupt the White Anglo-American, and the Japanese would continue to remain silent.

In a study of the cross-cultural miscommunication of British and Asian speakers of English, Gumperz, and Roberts (1980) found that each group had its own list of irritants that impeded the communication. For th...