![]()

Part I

Tropes of “Turkishness” from Sufism to State

![]()

1

Literary Revisions of the Secular Modern

I don’t want to be a mangy Turk.

(Pamuk 1996a [1982]: 131)1

A person who publicly denigrates Turkishness [Türklük], the Republic or the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, shall be sentenced a penalty of imprisonment for a term of six months to three years.

(Article 301–1 Turkish Penal Code 2004)2

The concept of the secular cannot do without the idea of religion.

(Asad 2003: 200)

Insulting Turkishness

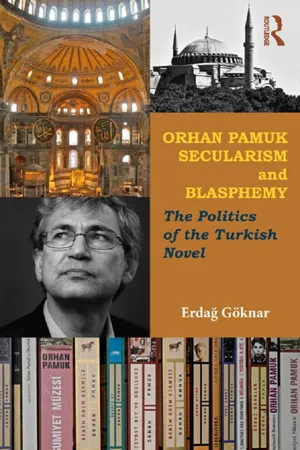

In 2005 Orhan Pamuk was charged with “insulting Turkishness” under Article 301–1 of the Turkish penal code.3 Eighteen months later he was awarded the Nobel Prize. After decades of criticism for wielding a depoliticized pen, Pamuk was cast as a dissident through his persecution and trial, events that underscored his transformation from national litterateur to global author. But what had triggered this clash between state and author? What was meant by “Turkishness” exactly? The charges centered on Pamuk’s affirmation of the ethnic cleansing of Ottoman Armenians in 1915 and Turkish Kurds in the 1990s, charges that emerged out of a secular state tradition of enforcing national identity. Yet, contrary to the dominant notion that Pamuk had been an apolitical author, his novels, in both content and form, had been transgressing official versions of Turkish history and identity for decades. So what had changed suddenly to make Turkey’s best-selling novelist an object lesson for state determinations of “Turkishness”?4

Another cultural logic was at play. Turkey had been emerging as an increasingly influential power between Europe and the Middle East. In the same year as Pamuk’s trial, the EU officially opened accession talks with Turkey (on October 3, 2005); the start of Pamuk’s trial was scheduled to coincide with the EU summit in December. The author had become the target of a secular establishment that had been marginalized by the 2002 election of the Islamically oriented AK Party and its spearheading of the EU-accession process. In short, a secular Republican dream of European integration had been appropriated by political Islam. Pamuk’s trial, though later dismissed, assumed greater significance in the context of EU-accession, which some nationalists now deemed a threat to Turkey’s sovereignty. Though secular himself and an advocate of Turkey’s EU-accession, the cosmopolitan author became a symbol of everything the national-secularists despised. Nationalists hoped to undermine EU relations by making a cause célèbre out of Pamuk – and they partially succeeded. But this is somewhat misleading. I argue that the real story didn’t rest with Pamuk’s trial, but with his fiction, which had been destabilizing official narratives of nationalism for decades. It was Pamuk’s writing that exposed the ambivalence and indeterminacy of “Turkishness” in the face of secular modernity. The story of his success, in fine, is both literary and geopolitical.

Scholars have long established that the novel in Turkish functioned as a vehicle of social modernization, in which secularism is centrally located (Evin 1983; Moran 1983; Finn 1984). I argue that the authoritarian history of Turkish modernization, in turn, politicized the novel as a social space, enabling it to be a fundamental forum for dissent. My argument emerges from the observation that in Turkey, the authority of literature has always contested the authoritarian tendencies of the state. The constant state-sanctioned exiles, imprisonments, and trials of authors from Namık Kemal in the nineteenth century to Orhan Pamuk in 2005 are a testament to the ongoing tensions between the dominant narratives of literary and secular modernity. These narratives could be synchronized to reflect the ideologies of early modernization, as they were in the secular masterplot of the Republican novel, which came to represent the nation, Turkishness, and the secularization thesis. However, Turkish modernity, predicated on the opposition between religion and secularism, did not manifest as a strict binary in the literary sphere. Innovations in form, technique, and content, or “literary modernity,” functioned to challenge narratives of the secular modern backed by state power.

In Turkey, the literary sphere often contests the authoritarian tendencies of the secular state.5 This chapter traces confrontations between “literary modernity” and the “secular modern” as conveyed through Pamuk’s work and the Turkish novel. Such an analysis reveals that narratives of the nation-state (or devlet), bound to the secularization thesis, have always been contested by politicized tropes of tradition, Islam, and Sufism (signifying din).

Pamuk as Dissident

Shortly after receiving the Nobel Prize, Pamuk accepted an invitation to serve for one day as editor-in-chief of the Turkish Istanbul daily Radikal. In this capacity of socially engaged journalism he ran a front-page piece in the January 7, 2007 edition about Turkish writers and artists who had been persecuted by the state, just as Pamuk had been before the Nobel award. The headline, LET ‘EM SPIT IN HIS FACE, was taken from a 1951 article that originally ran in the staunchly secular-national newspaper Cumhuriyet (The Republic) about dissident poet Nâzım Hikmet. Though 56 years had passed, this time it referred to Pamuk as well who had also been labeled a vatan haini, a “traitor to the nation.” The group Pamuk assembled included dissident authors of socialist engagement, Nâzım Hikmet, Yaşar Kemal, and Sabahattin Ali. Pamuk also made room for singer Ahmet Kaya, who was prosecuted for a pro-Kurdish stance, and ran a piece on the Ottoman writer Ahmet Midhat Efendi, a forefather of the modern Turkish novel who happened to be traveling in Stockholm for the 1889 International Conference of Orientalists over one century before Pamuk received the prize in the same city.6

The starting point of this chapter is an instructive discrepancy. The dissident status of the author in the international arena, which was confirmed through his prosecution under Article 301–1 rose in direct contradiction to his authorial past. Pamuk’s new political positioning was ironic, for he’d spent the early part of his literary career as the lightning rod for criticism about his own social and political disengagement. He’d often been attacked as a representative of the depoliticized literature of the post-1980 military coup. An Istanbul author from a bourgeois background, he described how he’d sequestered himself in an ivory tower. In a 2004 New York Times interview, he insists:

I was not a political person when I began writing 20 years ago. The previous generation of Turkish authors were too political, morally too much involved. They were essentially writing what Nabokov would call social commentary. I used to believe, and still believe, that that kind of politics only damages your art. Twenty years ago, 25 years ago, I had a radical belief only in what Henry James would call the grand art of the novel.

(Star 2004, my emphasis)

Given that Pamuk-as-editor later associates himself with the very generation of Turkish dissident authors he here disavows, how are we to interpret the statement “that kind of politics [engaged literature] only damages your art”? What should we make of the fact that since his Nobel award he has generally refused to explicitly comment on or engage in matters of politics?

The group that Pamuk assembled in newsprint could be read as part of an authorial fantasy about solidarity with a socially engaged tradition of Turkish writing.7 Granted, his first novel, Cevdet Bey and Sons, does bear the influences of the social realism that informed the Republican novel. But he quickly rejected and was soon excluded by the practitioners of this variety of Turkish literature. In Turkey, a country whose national identity has been constructed upon the unstable nexus of modernity, secularism, and Islam, the significance of aesthetic innovations in literature, or “literary modernity,” stems from its often-negative relationship to secular state power.8 In Turkey, “literary modernity” describes transformations in literature that often transgress Republican articulations of secular “Turkishness.” “Literary modernity” in the Turkish novel is not merely innovation in form and content, but a foundational means of critiquing of what cultural anthropologist Talal Asad terms the “formations of the secular” (Asad 2003). Thus, “literary modernity” describes a persistent conflict between literary authorship and the authority of the state and its modernization history, one that can be traced in Pamuk’s oeuvre and much of the Republican literary canon. In this study, this concept enables the Turkish novel to be read with or against narratives of the secular modern.

Pamuk’s stated ambivalence toward the Turkish literary tradition is a clue that Pamuk-as-editor is doing much more than expressing belated solidarity with the literary left. Rather, he is attempting to reconcile his position in the Turkish national tradition with his international identity as a dissident author confirmed and validated by the Nobel Prize.9 In this sense, he demonstrates the type of mediation between national and world literatures that is a hallmark of his novels. But this is still only half the story.

A critical examination of the discrepancy between Pamuk’s “disengagement” and “dissidence” provides a measure of his literary modernity. His work experiments with techniques from social realism to metafiction before settling into innovative forms of Istanbul cosmopolitanism that synthesize internal and external influences. These transformations in literature present “Turkishness” as being contingent on a multitude of cultural contexts beyond ethno-nationalism, including the Ottoman past, Sufism, Islam, and even orientalism. Pamuk uses the novel form, I am suggesting, to pose persistent political challenges to the state and the secularization thesis that informs Turkish modernity.

In part, the politics of Pamuk’s novels emerge through innovations in literary form that interrogate the “secularization thesis” rather than from ideological disputes per se. It is not Pamuk’s resemblance to dissidents like Nâzım Hikmet, but his rejection of the literary forms of social realism as understood by a previous generation of writers that first made him anathema in Turkish leftist and nationalist circles. Novels that turned away from the projects of Anatolian socialism and nationalism to recoup the cosmopolitan cultural history of Istanbul’s Ottoman and Islamic past could only be read as incongruent with 1980s Turkey. In the wake of Pamuk’s work, however, novels of cultural and historical redefinition have become the norm. In transforming the Turkish literary field, his writing makes an often-overlooked political commentary on secularism. As such, the overriding tensions between Istanbul cosmopolitanism and Republican nationalism (focused on Anatolia) provide the background for Pamuk’s own intervention, one that pits city against nation.

Understanding Pamuk’s literary modernity as a form of political engagement is vital to an informed understanding of how his novels think. A lack of international access to the Turkish cultural contexts of Pamuk’s work has led to half-formed interpretations, misconceptions, and misreadings by Euro-American commentators. Even worse, the general lack of Turkish cultural legibility has resulted in a critical silence surrounding his novels that reveals the de facto acceptance of Pamuk’s “dissidence” with a concomitant dismissal of his literary project. This study directly addresses this inversion in his reception, in which political concerns obliterate the nuances of cultural production.

The first point to be made is that the “literary modernity” of Pamuk’s own fiction does not correspond to the dissident social realism with which he identifies as editor-in-chief. Pamuk does not hide his ambivalence and even animosity toward traditions of the Turkish novel, which nonetheless influence him.10 Thus, what is more likely being revealed in Pamuk’s edition of Radikal is a post-trial, post-Nobel fantasy of a return to origins after being labeled a national “traitor”; an attempt to resituate himself in the literary canon, as if to say “I am still one of you!”; or even something of an apology for his questioning and transformation of the dominant discourses of “Turkishness” and the forms of secular literature. Interestingly, this very transformation has placed the Turkish novel, to borrow Pascale Casanova’s phrase, into the “world republic of letters” (Casanova 2004). Meanwhile, Pamuk himself has been alienated from the space of Turkish Republican culture and is frequently misunderstood in international circles as a native informant or an exile. For a time, like his poet-protagonist Ka in Snow, Pamuk needed bodyguards and was forced to leave the country following death threats. This paradoxical displacement of the Turkish Nobel laureate and his perceived “inauthenticity,” in addition to the silence of his critical reception, serve as additional background contexts for my argument.

Though Pamuk’s work belongs to the post-1980 “Third Republic,” characterized by Turkey’s gradual neo-liberal integration into global networks, he began writing in the early 1970s, during a period marked by social realism and political unrest known as the “Second Republic” (between the 1960 and 1980 military coups).11 Pamuk states:

When I decided to become a writer … the dominant view was that serious writers worked collectively, and their work was valued for the way in which it contributed to a social utopia and reflected a shared vision (like modernism, socialism, Islamism, nationalism, or secular republicanism). There was little interest in literary circles in the problem of the individual creative writer who drew from history and tradition, or who tried to find the literary form that best accommodated his voice. Instead literature was allied to the future: its job was to work hand in hand with the state to build a happy and harmonious society, or even nation. Utopian modernism—be it secularist, republican, or socialist egalitarian—has had its eyes so firmly planted on the future that it has, I sometimes think, been blind to the heart and the soul of just about everything that has gone on in the streets and houses of Istanbul over the past century.

(Pamuk 2008)

Pamuk draws from history and tradition, experiments with form, ...