- 254 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Spanish Language Today

About this book

The Spanish Language Today describes the varied and changing Spanish language at the end of the twentieth century. Suitable for introductory level upward, this book examines:

* where Spanish is spoken on a global scale

* the status of Spanish within the realms of politics, education and media

* the standardisation of Spanish

* specific areas of linguistic variation and change

* how other languages and dialects spoken in the same areas affect the Spanish language

* whether new technologies are an opportunity or a threat to the Spanish language.

The Spanish Language Today contains numerous extracts from contemporary press and literary sources, a glossary of technical terms and selected translations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Spanish Language Today by Miranda Stewart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Spanish as a world language

1 The extent and status of Spanish in the world

1.0 Introduction

At the end of the twentieth century Spanish is spoken by approaching 400 million people throughout the world, and as such is the fourth most widely spoken language in the world after Mandarin Chinese, English and Hindi. It is an official language, generally the sole one, in twenty-one countries. It is spoken not only as a mother tongue but as an important second language (for example in Paraguay where it enjoys co-official status with the indigenous language of Guaraní) and also as a vehicular language or ‘lingua franca’. While the Spanish language is most readily associated with its country of origin, Spain, the majority of its speakers live in Latin America where population growth means that numbers of speakers are steadily on the increase. It has a vibrant and rapidly expanding presence in the United States. It is also represented, albeit by small and declining numbers of speakers, in Africa, Asia and the Middle East. In this chapter, we shall look at the Spanish-speaking world and at the current status of Spanish today as a major world language.

It is clear that the number of speakers is but one factor in assessing the status of a language: many other considerations such as its status as an official, co-official or minority language, the economic and cultural potential of the countries where it enjoys official status, the number of those who study it as a foreign or second language, the extent of the domains in which it can be used, its presence in supranational forums, and the efforts expended on its promotion are all factors which contribute to the status of a language.

1.1 The extent of Spanish in the world

1.1.0 Spanish in Latin America

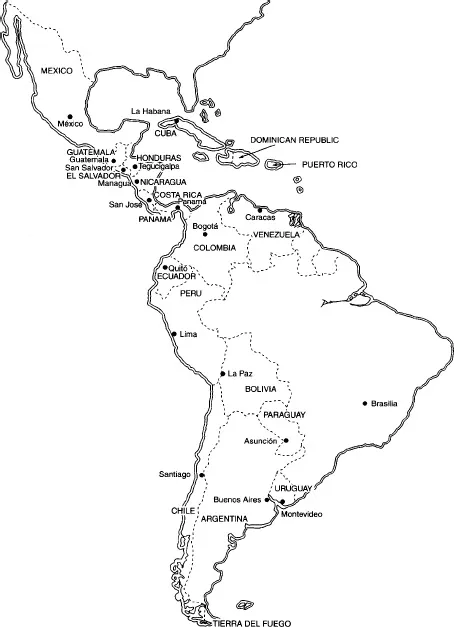

Spanish is the official language of Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay and Venezuela (see Figure 1.1). In the case of Puerto Rico it shares this status with English, in Paraguay with the indigenous language Guaraní, in Peru with Quechua and Aymara and in Bolivia with Aymara. It is also spoken in the former British colony of Belize, on the borders of Guyana and Haiti and in isolated communities in Trinidad. Mexico with a population of some ninety-three million, more than double that of Spain provides the greatest number of Spanish speakers, followed by Argentina and Colombia with approximately thirty-five million inhabitants each. It should be remembered, however, that the process of Castilianization of indigenous populations, while wide-ranging and rapid, is not complete and many countries still have groups of monolingual speakers of indigenous Amerindian languages.1 Throughout Latin America bi- and multilingualism are commonplace whether between Spanish and the indigenous languages or Spanish and other languages of colonization, for example, Italian and Portuguese. Indeed, care needs to be taken when interpreting figures relating to proficiency in a second language as there may be wide disparities between the literacy claimed for an individual and their ability, opportunity or desire to use that language proficiently. Spanish represents the language of social mobility and functions as the High variety, used, for example, in education and public administration. The indigenous languages serve as the Low variety used, for example, in the home and among the immediate speech community. Interestingly, this is even the case for Guaraní, a co-official national language which enjoys considerable prestige.

Figure 1.1 Map of Spanish-speaking nations of Central and South America (based on Mar-Molinero (1997))

1.1.1 Spanish in Spain

In Spain, Spanish is spoken by approximately 40 million people of whom some 40 per cent are bilingual in one of Spain’s minority languages (see Figure 1.2). One of the most distinctive features of post-Franco Spain is its emergence as a decentralized and plurilingual country after a period during which severe, albeit lessening, repression of minority languages was exercised in the interests of achieving a centralized, monolingual state.2 As a reaction against the linguistic illiberalism of this period typified by Franco’s vision of national unity, ‘la unidad nacional la queremos absoluta, con una sola lengua, el castellano, y una sola personalidad, la española’ (Sala 1991), the Constitution of 6 December 1978 sought to redress the balance and offer a measure of protection to minority languages, henceforth seen as part of Spain’s rich cultural diversity. Nevertheless, the Constitution clearly established Spanish as the official state language despite the many compromises apparent in its drafting, and in Article 3.1 declares:

El castellano es la lengua oficial del Estado. Todos los españoles tienen el deber de conocerla y el derecho a usarla.

(Siguan 1992:75)

Thus, the intention is clear that monolingualism in any language other than Spanish is not permitted to the Spanish citizen and in effect virtually does not exist. Article 3.2 provides for the co-officiality of the various minority languages or lenguas propias but only within their autonomous communities and not throughout the national territory. Thus Spanish is still very much the language of majority use in Spain and of Spaniards outside Spain despite strenuous efforts by some minority cultures, particularly the Catalans, to express themselves through the medium of their own language nationally and internationally.

Figure 1.2 Map of Spain showing linguistic and dialect divisions (based on García Mouton (1994))

1.1.2 Spanish as the second language in the United States

Spanish is currently spoken as a first language by approximately twenty-two million people3 in the United States. Approximately 60 per cent are Mexican in origin and are concentrated in the south west; Puerto Ricans (12 per cent) tend to live in the north east, and principally New York, while the Cubans (4 per cent) favour Florida. The Hispanics are currently America’s fastest growing ethnic community and their numbers are set to rise to 96.5 million by 2050 (The Guardian, 16.07.98). This is not without problems as the United States does not have legislation which states that English is the official language of the Union; it has always relied on the desire of immigrants for social assimilation and mobility to consolidate the pre-eminence of English. However, friction is now arising between increasingly monolingual Spanish communities and the English-speaking majority, particularly in the southern states where the Hispanic communities are concentrated. In some major cities such as San Antonio and Los Angeles up to one half of the population is of Hispanic descent, and even in New York one tenth of the population is Spanish-speaking.

In the 1990s the Republicans have been active in seeking official status for English and in seeking to limit the use of Spanish mainly outside but also inside the home and they have promoted an ‘English only’ movement. They are particularly unhappy about the proportion of the state budget devoted to mother-tongue maintenance programmes. However, there has been active resistance on the part of the Spanish-speaking community. In 1994 a federal tribunal ruling in the state of Arizona turned down state legislation prohibiting state employees from using the Spanish language in their official duties on the grounds that it infringed the first amendment of the Constitution. This enabled, for example, administrators in the state administration to deal in Spanish with complaints about healthcare services by Hispanic citizens who were not fluent in English. In San Antonio (Texas), the ninth biggest city in the US, a resolution was passed in 1995 proclaiming the city to be bilingual. In June 1998, however, the Spanish language received a major setback with the United States’ most populous state, California, voting for what was called Proposition 227. The effect of this was to end more than twenty years of bilingual education for immigrant children. While the aim is to prevent Hispanic children from being ghettoized and marginalized through lack of proficiency in English, it will be interesting to chart its effects on the use of Spanish amongst the Hispanic community and the status of the language within the US.

1.1.3 Spanish in the rest of the world

Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea is a fragmented nation on the west coast of Africa with a tiny population which stood, in 1991, at some 335,000 (Quilis 1992:205).4

Spanish was recognized as the country’s official language in 1928 and is spoken in general use and as a lingua franca alongside seven indigenous Bantu languages, a Portuguese creole and an English pidgin. After a period under the dictatorship of Macías where indigenous languages, and particularly fang, were promoted, independence in 1979 heralded a time of improved relations with Spain and an increase in the use and status accorded to Spanish. However, in the 1990s, there appears to be a rejection of Spanish in favour of French as a trade language, primarily for geo-political reasons; in September 1997 the President, Teodoro Obiang, announced that French would become, in the short term, the official language of the country (El País, 23.9.97).

Guam

Guam, a United States colony in the Pacific Ocean, has a Spanish-speaking minority numbering some 780 in 1980 (Rodríguez-Ponga, in Alvar, 1996a:245) and who are of Spanish, Latin American, United States and Philippine ori-gins. Additionally, some vestigial Spanish is spoken by older speakers of the predominantly Spanish-lexified creole, chamorro, used by almost 30 per cent of the population, with further speakers in the northern Marianas Islands and in the United States. On Guam chamorro enjoys co-official status with English.

North Africa

Until the independence of Morocco in 1956, Spanish was a co-official language alongside Arabic in the northern part of the Protectorate. Since independence Spanish has ceded ground to French although Quilis (1992:201–2) has noted a recent slow recovery which he attributes to Spain’s policy of creating a number of Spanish-medium primary and secondary schools, to access to Spanish-language broadcast media, and to nationalist feelings in part due to what is perceived as preferential treatment given to French-speaking areas. Radio Rabat provides five hours a day of its broadcasting in Spanish and the French-language newspaper, L’Opinion provides a weekly Spanish-language supplement, Opinión semanal.

Spanish is also spoken in the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla where approximately 15 per cent of the population is Spanish in origin and by a small number of elderly Spaniards resident in Tangier where a proportion of the population is bilingual in French or Spanish and Arabic or trilingual in all three.

Andorra

Here the official language is Catalan which coexists with Spanish, predominantly in the south, and French, predominantly in the north. There are approximately 33,000 users of Spanish.

Ladino or Judeo-Spanish

Ladino or Judeo-Spanish is a variety of Spanish preserved by the Sephardic Jews who were expelled from Spain in 1492 and went to settle not only throughout Europe, North Africa and the Middle East but also further afield, for example to the United States of America. Currently the largest Sephardic communities are located in the United States and Israel. However, in these communities, as elsewhere, ladino is being ousted by the dominant language, English or Hebrew, or, in the case of a second language, modern Spanish. Harris (1996) notes that it is used by increasingly fewer speakers, mainly those over the age of seventy, and in increasingly fewer domains, often only with elderly relatives, for entertainment, for example for singing romanzas and as a humorous or secret language. She further argues (1996:45) that 60,000 would be a generous estimate of the number of proficient Judeo-Spanish speakers, of whom none are monolingual speakers of the language and none are passing it on to their children. The United States has given very little institutional support for the language and support in Israel is diminishing. Here, until recent years there had been a thriving press in ladino but today this has dwindled virtually out of existence, as have audiovisual broadcasts, with the radio station Kol Israel being pressed to give up its Judeo-Spanish broadcasts. There is one journal written completely in Judeo-Spanish, Aki Yerushalayim, still in existence mainly due to the efforts of its editor, Moshe Shaul. Indeed, it is to be expected that within a generation this variety of Spanish will disappear as a living language.5

Philippines

Spanish in the Philippines is, according to Lipski (1987b), in the process of language death with, already by the 1980s, few proficient speakers under the age of forty. Despite three hundred years of Spanish presence in the Philippines the language did not strike firm roots. It never became a trade language and the Church and the administration preferred to use indigenous languages in pursuit of their goals. From 1898 onwards, the United States, which had won the Philippines from Spain, invested heavily in English-language programmes and precipitated the decline of Spanish. In line with the linguistic reality of the country, the Philippine Constitution of 1987 effectively demoted Spanish from its previous status as a co-official language alongside English and Filipino (Tagalog), stating that it, along with Arabic, ‘shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis’. It is difficult to obtain the precise numbers of Spanish speakers as censuses do not distinguish between speakers of Spanish and of Spanish-based creoles (chabacano).6 Despite being brought to the Philippines via Mexico, the Spanish spoken here is closest to central and northern Peninsular Spanish and has few features, mainly lexis, from Hispanic America. Interestingly, and unlike the case of Philippines English, there is virtually no geographical variation within Philippines Spanish. It is spoken primarily by Euroasian mestizos of Hispanic descent, many of whom have close relations with Spain, who have tended towards intermarriage over the centuries. This group, primarily descended from wealthy landowners, has struggled to keep the language alive but now appears to be losing the battle. In addition to these speakers, there are others who have acquired levels of proficiency through education (until recently Spanish was a compulsory subject at university), profession (many lawyers have high levels of proficiency insofar as the legal code is drafted in Spanish, there are also a number of convents run by Spanish orders), or simply language contact (knowledge, for example, of Philippine Creole Spanish (see 9.0.1), facilitates a passive understanding of the language).

1.2 The status of Spanish as a world language

As we have seen, Spanish is clearly a world language in terms of the number of countries in which it has official status and in terms of the numbers of speakers who use it as a first language or as a prestige variety. Its centre of gravity lies clearly in Latin America where the bulk of its speakers live; in Europe, in terms of native speaker numbers it comes after Russian, German, French and English. Nonetheless, it should be recognized that Spain, one of the faster developing economies of Europe (The Economist 1996:93–100), is proportionally much stronger eco...

Table of contents

- Cover

- The Spanish Language Today

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I: Spanish as a world language

- Part II: Spanish: variation and change

- Part III: The Spanish language in use

- Part IV: Spanish in contact

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Glossary

- Selected bibliography and further reading Other sources

- Index