![]()

1

Beauty

For I would give you of your art some adequate notion of its possible beauty, its endless capacity for expression, its fluency, its lyric quality, its inexhaustible dramatic power—when it comes into kinship with Nature’s rhythms.

Louis Sullivan, The Kindergarten Chats

The word beauty, as Roger Scruton informs us in his suggestive study of the theme, has a decidedly classical, anti-modern ring to it.1 Alongside such consummate terms as the “good” and the “true,” it has enjoyed a comely aura of mystery and— at times—divine sanctification in its repeated invocation over millennia. It is an exalted term employed in all social circles, a potent word laden with deep emotional coloration. At the same time, in its adjectival form, it is one of the most frequently used words in the English language, with applications that often border on the mundane. We speak of beautiful objects and ideas, beautiful qualities or attributes, the beautiful movements of a dancer, beautiful mathematical equations, beautiful scenes of nature, beautiful friendships, beautiful days, and of course beautiful people. When a chef prepares a particularly inviting plate, we take note of its beautiful presentation. The musical interplay of a string quartet is for many a thing of beauty. Beauty, then, can be intellectual or sensory, abstract or material, but always something associated with pleasure. The word also possesses a distinct charm, captivation, fascination, enthrallment, and, on occasions, the irresistible and coquettish force of a passionate seduction.

Yet within the critical parlance of art, the term has suffered a spectacular downfall. Classical antiquity was obsessed with the concept; epic poetry and the Trojan War were born from the beauty of Helen. And when the city of Girgenti commissioned Zeuxis to paint her portrait, the artist had the town’s maidens paraded naked for his review, from whom he selected five whose individual features collectively approached his high ideal of beauty. Medieval Catholicism was similarly enamored with beauty’s moral force, and even saintly Augustine confessed to writing “two or three” books on “the fair and fit,” which unfortunately for us had “strayed” from his possession.2 The representation of female beauty, once secularized, constituted the heart of Renaissance theory, a mystique that we can follow from Dante’s Beatrice, through Botticelli’s Venus to the plump nudes of Rubens. By the eighteenth century, the many dimensions of beauty—human, natural, and artistic— had come to dominate philosophical discourse, but the lure of the word began to wane with the onset of the industrial age. By the start of the twentieth century, the word “beauty” nearly disappears from artistic theory, and this was especially the case within avant-garde circles following World War I. Picasso and Malevich took no note of it, and Duchamp’s urinal was a conscious affront to the very concept. Toward the end of the century, it was difficult to find more than a handful of artists who would deign to utter the word in public, let alone let their art be associated with it. The very concept of beauty had fallen out of favor, or worse, had been pushed to the point of supreme irrelevance.

The course of architectural theory follows a similar path. Beauty was one of the three foundational stones of Vitruvian theory, and notably the Roman architect preferred the more sensuous term venustas (derived from the goddess Venus) to the more abstract concept of pulchritudo. Leon Battista Alberti allotted two of his ten books to explaining the difficulty of achieving beauty, and Palladio, a century later, was similarly convinced of its absolute and divine nature. Even the more skeptical seventeenth-century Frenchman Claude Perrault, who was intent on declaring French independence from Italian canons of absolute beauty, was forced to proffer an alternative model of positive and relative beauty. In the eighteenth century, discussions of beauty and its sister concept, the sublime, ruled the day, and beauty remained the centerpiece of architectural theory up until the time of Karl Friedrich Schinkel.

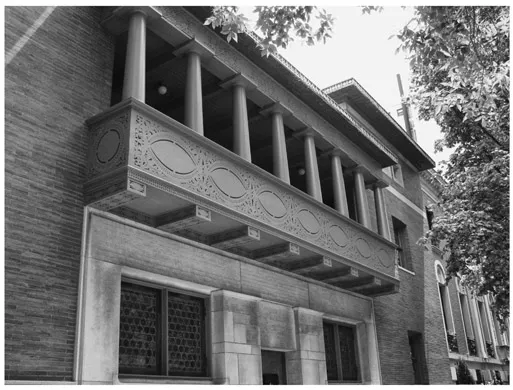

But once again, industrialism changed the terms of the game. Of the major theorists of the mid-nineteenth century, only John Ruskin, the vehement anti-industrialist, privileged beauty as one of his seven lamps and the central motif of his aesthetics, and one of the last major architects to wax poetically on the term— as we see in both his ornamental patterns and the grandiloquent statement above— was Louis Sullivan3 (Figure 1.1). At the same time this architect helped to plant the destructive seed of pairing beautiful form with function. Functional things are rarely endowed with the appellation beauty, and the loss of beauty’s relevance to architectural theory, in this and in many other ways, played out over the course of the twentieth century.

But in the last few years the notion of beauty has been making a comeback in many circles within the sciences and humanities. Books and papers on the theme are again being published and, as fMRI studies have recently disclosed, there is something neurologically tangible to the aesthetic experience that we define as beautiful. Beauty, it seems, is deeper than the skin and it translates into neural activity far more biologically distributed than the eyes of the beholder. And although the idea of an objective standard for beauty remains as elusive as ever, we seem to be entering a new era in which beauty once again might have something to say to the designer. Could it be that the last two centuries of theory have steered us wrongly with respect to this elusive concept? Might the pursuit of beauty really have a biological foundation and some evolutionary purpose? Is it proper or even possible to reclaim this curious word from the annals of history?

Figure 1.1 Louis Sullivan, Charnley Persky House, Chicago (1892). Photograph by author. Grinnell, Iowa (1914). Photograph courtesy of Tim Brown Architecture.

Darwin’s Haunting

Charles Darwin is of course best known for his theory of natural selection. First sketched in 1859 in On the Origin of Species and elaborated upon twelve years later in The Descent of Man, Darwin’s theory has proved to be remarkably accurate and resilient, and today it remains an essential underpinning of the biological sciences. It posits that, through competitive and environmental forces, biological organisms over successive generations come to develop certain heritable traits that allow the organism, and its progeny, to function better and survive. Breeders are predisposed to perpetuate these attributes and therefore choose mates that best exhibit them. Yet, as Darwin himself famously admitted, the earlier theory of natural selection failed to account for a few curious phenomena in nature—one of which was the extravagant plumage of birds, such as peacocks. If the human brain, for example, had increased its size and neural efficiency over time, allowing this species to compete successfully against stronger and more lethal predators, what possible advantage would accrue to the seemingly excessive plumage of the peacock, which in fact inhibits the male from taking flight against predators? Darwin’s answer in 1871, as a complement to his theory of natural selection, was his addendum of “sexual selection.” Peahens, with their finite egg production over their mating life, are biologically predisposed to seek out the fittest males for reproduction, and the colors and elaborate patterns of the peacock’s tail are his way of displaying superior genetic lineage and thereby ensuring the same in his offspring. With this single stroke, beauty, and with it other aspects of survival “fitness,” were inserted into the biological equation and Darwin’s extended musings on the term in fact reflect more than a passing interest in the phenomenon of beauty.

Such an explanation received little attention in the nineteenth century, but it starled to gain experimental traction in the second half of the twentieth century as biologists, sociologists, and psychologists began to ponder the role that beauty— as an indicator of biological fitness—plays in human courtship and sexuality, and how human beauty even affects such things as social relationships and career advancement.

In 1979 the psychologist Donald Symons began to outline his “adaptationist” thesis, which argued that sexual attractiveness, particularly female beauty as viewed by males, is an indicator of nubility and health.4 He pointed out that in most indigenous cultures, females traditionally marry at the onset of puberty, or when they are just beginning ovulation and are highly fertile. And because fecundity cannot be directly observed, males seek out females who have reliable cuing factors indicative of good health. Over time, these indices evolve into psychological mechanisms that selectively respond to certain human characteristics. In essence, Symons argued, there are inborn or adaptive templates of beauty by which people judge the attractiveness or fitness of others, both males and females. Although some of these variables may be culturally conditioned, most in fact are biologically driven from below and therefore constitute what Nancy Etcoff describes in visceral terms as “a response to physical urgency.”5 Moreover, these adaptations are universal in the sense that they are shaped by sexual selection. The often-discussed series of experiments by Judith Langlois, in which babies, as early as two months of age, prefer to look at photographs of attractive faces over less attractive ones lends much credence to this thesis.6 A number of other studies have pointed to the cross-cultural similarities in judgments of human facial beauty, suggesting that even if the cultural standards regarding beauty continue to shift over time, the “underlying selection pressures” that shaped these standards are the same.7

Over the last few decades, psychology labs have devoted much research to exploring just what these attributes of human beauty and fitness really are. Some have pointed to the anatomical importance of waist-to-hip ratios, the symmetry and geometrical proportioning of the face and other body parts, skin condition, and a host of other factors. In the first regard, pre-pubic boys and girls have similar waist-to-hip ratios, but as a girl enters puberty, under the influence of estrogen, her pelvis widens and she gains weight in the hips and thighs—the so-called reproductive fat needed to support the physical ordeal of pregnancy. Therefore, as several experimental studies have suggested, a “fit” female waist-to-hip ratio (deemed to range between .67 and .80, with the optimal usually set around .70) is a reliable predictor of both fertility and good health. In fact, women with lower ratios have been shown to become pregnant more easily than those with higher ratios. Conversely, the presence of testosterone in pubic males shapes the body with greater fat in the abdomen, neck, and shoulders; a male’s ideal hip-to-waist ratio has been set between .85 and .95.8

The human face has perhaps received the most attention experimentally, with the understanding that the brain seems able, almost instantaneously, to recognize a good facial “Gestalt.” We now know that we have a particular area of the brain (the “fusiform face area” or FFA) specialized in perceiving or recognizing faces, and it works with extreme efficiency—by some accounts in about a seventh of a second. Symmetry is an important feature in this regard because, as psychologists often argue, it assists in the recognition of objects in general and thereby falls in line with the sensory system of the perceiver. Psychologists have also emphasized the importance of “averageness” or the increasing attractiveness of composite faces, which they similarly attribute to evolutionary pressures. In the explanation of Symons, the face-recognition area of the brain operates “in a manner analogous to composite portraiture: the mechanisms (unconsciously) average—presumably with appropriate age-corrections—the faces each individual observes, and thereby generate a male and a female template of facial attractiveness. Deviations from a template, in this view, reduce attractiveness.”9

Some studies have stressed the importance of slight deviations from these norms in cases of exceptional facial beauty.10 Others suggest that more attractive female faces have higher cheekbones, larger eyes, a thinner jaw, and a smaller distance between the nose and mouth than between mouth and chin. The faces of attractive males, by contrast, are more oval or rectangular in overall form, with heavy brows, deep-set eyes, and wide, muscular chins. To some, their faces more typically portray dominance rather than beauty.

Skin is also an obvious predictor of health, in that it easily reveals any chemical, fungal, bacterial, or parasitic disorders. Flawless skin is considered by many to be one of the most desired attributes of human beauty, and a few have remarked that the downy nakedness of the human body, in early human history, came about not only because it increased endurance in running and eliminated a home for lice and fleas but also because it intensified the pleasure of sexual contact. Females, in general, have lighter skin than males, and in fact female puberty brings with it a lightening of the skin (more so near ovulation), which disappears with pregnancy. And whereas female hair is generally removed from all visible areas of the body, a female head with long, healthy hair is everywhere deemed to be another important feature of beauty. Part of the explanation for this is the biological fact that hair grows faster (and therefore tends to be longer) in early womanhood. It could also be that, as some have more recently conjectured, longer hair better distributes pheromones produced in the apocrine glands.11

The human capacity to transmit and smell these hormonal substances has only recently come to light, in part because their effect takes place through a different olfactory system than our main smell centers. We now know that they greatly influence our behavior and our sexual attraction to others. Females have a better sense of smell than men, and this keenness is particularly acute during ovulation. Some experiments have shown that women favor the pheromones of symmetrically built men, as well as of men who smell the least like themselves— probably for the genetic reason of complementing their own resistance to certain diseases in their offspring. Men seem to be particularly at...