1 Introduction

Education and popular culture

Education and popular culture are in some contexts considered to be almost antithetical concepts. Education is for enhancement and enrichment; it is about knowledge and learning. High culture might be spoken of in similar terms. But, for some, the notion of popular culture is still associated with the banal and trivial. Even those people who admit to enjoying popular culture can be dismissive of its value or significance. The assumption appears to be that if culture is popular then, by definition, it is likely to say little of note and to offer nothing that is educative. However, if you have decided to look at this book, it is unlikely that you subscribe wholeheartedly to the latter perspective, and more likely that you are among those who believe that popular culture is of interest and worthy of some serious consideration. Maybe as readers we should position ourselves where art teacher Katherine Watson, played by Julia Roberts in the film Mona Lisa Smile (2003), seeks to take her students: ‘Do me a favour; do yourselves a favour. Stop talking and look. You’re not required to write a paper. You’re not even required to like it. You are required to consider it.’

Popular culture is part of our lives. With education, it forms a dynamic of contemporary existence. It appeals because it speaks to interests and anxieties that are widespread within the societies that produce it. It does not seek to impress; it seeks to entertain and to sell. In this book, however, what concerns us is not so much popular culture in general but rather the textual synthesis between education and popular culture. More specifically, we intend to explore how the people and places that are involved in education are represented in and through popular culture; how schools and colleges, teachers and students are portrayed in film, on television, in novels and through song lyrics. Each of us has been a pupil or a student, and, in school, we were the audience, producers and consumers of the multifaceted text that is contemporary education. Reading this book and studying the way in which education is represented in popular culture offers us an opportunity to be that audience again and, in doing so, to examine how society’s and our own ideas about education are constructed and represented:

The whole life of those societies in which modern conditions of production prevail presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. All that once was directly lived has become mere representation … The spectacle cannot be understood either as a deliberate distortion of the world or as a product of the mass dissemination of images. It is far better viewed as a weltanschauung that has been actualised, translated into the material realm – a world view transformed into an objective force …

The spectacle is capital accumulated to the point where it becomes image.

(Debord, 1995, pp. 12–13, 24)

What is this book?

Donnie Darko, Mean Girls, Grange Hill, School of Rock, Teachers, The Simpsons, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Busted and Britney – images of and references to teachers, lecturers, trainers, pupils, students, schools, colleges, universities, teaching, learning and education abound throughout all genres of popular culture. What views of education and educators emerge from this wealth of material? What do such texts suggest about the educational concerns of the societies that produced them? What do they indicate about educational ideologies and priorities, about the tensions that might exist between different perspectives? How do popular cultural texts convey the effect and impact of education on individuals and communities? What do they suggest about our fears and expectations of education, about the challenges it offers, the desires and disappointments it creates? How do these texts relate to other educational discourses: for example, those of professionals, academics and policy-makers? These are the kinds of question this book aims to explore by its review and analysis of some relevant examples of popular culture.

There has always been an interface between fiction, art and educational ideas and practice. In 1965 Maxine Greene’s classic work The public school and the private vision (republished 2007) examined the relationship between literary works and the writings of school reformers. Recently, there has been a growing body of academic work concerned with the representation of teachers, young people and education. This includes Brehony (1998); Cohen (1996); Dalton (1995); Daspit and Weaver (2000); Farber et al. (1994); Fisher (1997); Giroux (1993, 2002); Jarvis (2001, 2005); Joseph and Burnaford (2001); Judge (1995); Mitchell and Weber (1999); Paule (2004); Shary (2002); Warburton and Saunders (1996) and Weber and Mitchell (1995). Some of this work, such as that of Giroux (2002) and Daspit and Weaver (2000), has been concerned with ‘decentring critical pedagogy’ by exploring how popular culture embodies alternative voices about education and by considering the way in which popular culture itself has a pedagogical impact. There is an element of this in this book. That is, we are interested in the way popular texts offer constructions of reality that compete with those offered by academic, state and professional discourses about education, and we attempt to identify where there are contradictions and intersections between these perspectives. We also recognise that texts will not be read in the same way by everyone and therefore try to suggest some of the different ways they might be received. Nevertheless, we want to be quite clear about our own position, interests and perspectives. We are white, British teacher educators, with the typical educated working-class backgrounds that characterise many in the teaching profession. We share a commitment to critical pedagogy and emancipatory politics and a concern about the narrow conceptions of vocationalism that now dominate much of the UK educational agenda. Inevitably, this shapes our readings of texts, even when we try to consider and offer alternative perspectives.

The selection of texts discussed in this book is not meant to be comprehensive or representative. Our theoretical perspective assumes no single ‘grand narrative’ about education that can be derived from the study of popular culture. It does not aim to produce a history of education in popular culture. We believe, instead, that there is a range of narratives and competing discourses circulating through popular culture and about education. Our readers will bring their own agendas and apply what insights they can. Our selection of texts reflects the interests and preoccupations we have as academics, professionals and individuals. Alternative voices could have been explored; some quieter and less obvious than those we have identified. There are also significant themes which have not been considered here: for example, educational management and leadership as exemplified in films such as Lean on Me (1989) and UK television programmes such as Hope and Glory (2000) and Ahead of the Class (2005). We, however, have focused on other issues that we feel have been particularly dominant in the discourses about schools and education in the UK, USA and Australia. These include, first, in professional terms, a fixation with criticising competence and rooting out ‘bad’ teachers while at the same time proposing ever more precise and restrictive definitions of the ‘good’ teacher. Second, in relation to the curriculum, there has been a preoccupation, particularly in the UK, with the skills agenda and the status of vocational education. Third, on a more pastoral note, we have identified a focus on sex, including both an increasing anxiety about teachers as potential sexual predators and a moral imperative to curtail the sexual activity of pupils and students. Pastoral care is also emphasised in the regulation of children’s and young people’s behaviour and relationships within school by means of anti-bullying strategies and other intervention techniques. Finally, in policy terms, we are concerned with the development of a lifelong learning agenda and its generation of training and regulation, particularly in the UK, for teachers in the post-sixteen sector.

The texts explored in this book are primarily from the USA and the UK, with an occasional reference to other English-speaking cultures. These are texts we know and that have interested and influenced us. When we ask others about popular cultural representations of education, these are the ones which are cited. They are texts to which our students and colleagues in all educational sectors relate and which they recognise. US popular culture is global in its impact, and the bias of our selection reflects this. There are examples from a range of genres: popular music, television drama, popular fiction, television cartoons and film. Although we do not rate any genre above another, the final category receives most attention because films set in schools, colleges and universities are ubiquitous. As diverse communities, educational institutions provide a rich source of conflict and comedy, drama and dialogue. Furthermore, the widespread distribution and commercial consumption of film, resulting from the global dominance of the US industry, give additional impetus to questions about the role of popular culture in reflecting and constructing our perceptions about education.

The wider field

Major categories of cultural production where representations of education can be found and analysed include popular fiction, biography and autobiography, film, magazines, comics and cartoons, television and radio, cyberculture and popular music. While this book focuses on the representation of educational themes in a limited range of popular cultural texts, we have included below a brief synopsis of how some of the categories listed above might relate to a more general consideration of education in popular culture. Although this is not a book about ways of utilising popular culture in the classroom, we hope and expect that it will stimulate some ideas about how texts can both inform learning and be of value as pedagogical tools (see Gregson and Spedding (2003) for a discussion of the use of popular culture in post-compulsory teacher training).

Popular fiction

Popular fiction features its share of teachers and learners. Commercially successful young adult fiction series such as Sweet Valley High, Point Horror and Point Crime are set in schools or colleges, as are a number of murder mysteries, such as those by Antonia Fraser, Reginald Hill, Dorothy Sayers and Amanda Cross. On a different note, the extensive collection of Miss Read stories (‘Miss Read’ is the pen-name of novelist Dora Jessie Saint) exemplifies the potential for using school as the site for a nostalgic representation of childhood and rural life.

A significant genre of school-based literature is aimed specifically at children, including Enid Blyton’s St Clare’s and Malory Towers series, Angela Brazil’s Chalet School books, Geoffrey Willans and Ronald Searle’s Molesworth books and Anthony Buckeridge’s Jennings series (set in an English prep school). More recently, J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter publishing phenomenon has demonstrated the commercial potential and individual appeal of school literature on the collective imagination of both UK and international readers. Popular fiction also has a capacity for transmogrification. To date there have been five very successful Harry Potter films (2001, 2002, 2004, 2005 and 2007), and more traditional literary texts have also been transmuted into cinema or television: for example, Nicholas Nickleby (films, 1947 and 2002; BBC TV series, 2001) and Tom Brown’s School Days (films, 1916, 1940, 1951, 1971 and 2004).

Biography and autobiography

In the context of the current ‘celebrity culture’, biography and autobiography are key non-fiction categories in book sales, and the majority of these have some reference to the schooling and educational experiences of their subject. Such books either set out to recount the life experiences of ordinary people with extraordinary stories or, alternatively, they chronicle the life histories of ‘the great and the good’, often showing, among other things, how school shapes young ideas and influences the adults we subsequently become. Accounts can offer an insight into individuals’ lived experiences of schooling and give space to alternative, even marginalised views of education. A number of autobiographical texts have also been produced around the experiences of teachers: for example, Educating Esme: diary of a teacher’s first year by Esme Raji Codell (2003), recounting her experiences in Chicago; I’m a teacher, get me out of here by Francis Gilbert (2004), based on his work in a London school; and Teacher man (2005) by Frank McCourt, which describes his life and work in New York schools. In 1995, the autobiographical account My posse don’t do homework by LouAnne Johnson (1992) was reissued under the title Dangerous minds after the film of the same name starring Michelle Pfeiffer proved a box-office success. Other autobiographical accounts, such as Roberta Guaspari-Tzavaras’ Music of the heart (1999) and Marie Stubbs’ Ahead of the class (2003), have also given rise to cinematic or television productions about their protagonists’ experiences within school.

Film

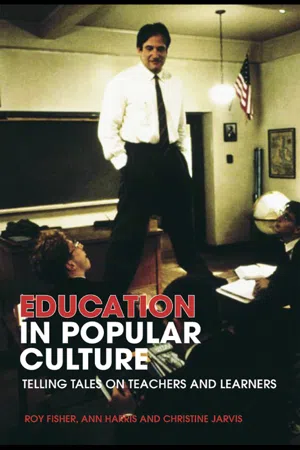

Educational institutions, teachers and learners have all featured strongly in the cinema. Films ranging from high farce (The Belles of St Trinian’s, 1954) to sentimental portrayals (Goodbye, Mr Chips, 1939, 1969 and 2002; Mr Holland’s Opus, 1995) can tell us something about the way in which society represents teachers, learners and the educational process. Dalton (1995, pp. 23, 24) has discussed ‘the way popular culture constructs its own curriculum in the movies through the on-screen relationship between teacher and student’ and expresses a belief that ‘general knowledge about the relationships between teachers and students, knowledge beyond the scope of the personal or anecdotal, is created by constructs of popular culture played out in the mass media’.

In recent years, owing to cinema’s increasing popularity, film has intensified its focus on youth with a stream of ‘teen flicks’, including romantic comedies, road movies and comic horrors that offer celebrations of youthful jouisance and teenage angst while also exploiting adolescent humour. Examples include Clueless (1995), The Faculty (1998), the American Pie series (1999, 2001, 2003), Ten Things I Hate About You (1999), Never Been Kissed (1999), She’s All That (1999), Save the Last Dance (2001), Thirteen (2003), Mean Girls (2004) and a host of others. Protagonists are generally at school or college, and the films cover themes such as: sexual experience; romantic relationships; friendships and school cliques; race and class issues; drug and alcohol abuse; parental control and oppression; grades and cheating; and music, dance and sport subcultures. Generally, however, despite dealing with some serious issues, these films offer a more comfortable and benign perspective on young people than the bleaker myths of previous generations and the brooding, intense performances of actors such as Marlon Brando in The Wild One (1953) and James Dean in Rebel without a Cause (1955). Nowadays, it is generally suggested that through insouciance, wit, energy and sheer good fortune, the young will triumph over adversity. See Pryce (2006) for a discussion of underlying moral messages and values in the American Pie series of films. Pryce (2006, p. 374) argues that these films seek to channel ‘adolescent sexual behaviour into approved routes’.

Cyberculture

The late twentieth-century ‘information explosion’, with its associated processes of technologisation and globalisation, has created new cultural forms and virtual products as well as new audiences for popular culture through worldwide communities of computer users, chat rooms, discussion boards and websites. Friends Reunited, which enables former schoolfriends in the UK to make contact and also features school reminiscences, is a cyberspace representation of educational experience that, through nostalgic reconstruction, reveals underlying values, beliefs, desires and traumas relating to education. In a similar vein, the contemporary enthusiasm for ‘blogging’ also encourages individuals to detail the minutiae of their lives, including, potentially, their feelings about key experiences such as education and employment as well as other social and domestic events that have touched them. Websites such as YouTube, which enable people to present their own films, have controversially featured embarrassing or salacious clips of teachers filmed covertly in their classrooms by students; the once relative sanctity of the classroom as the dominion of the teacher has therefore been fatally breached.

Cyberculture creates a unique market place. It offers the potential for marginal alternative culture to be popularised through global communication, and it has helped to generate an environment in which education itself, through e-learning, is presented as a commercial and globally accessible commodity.

Comics and cartoons

Comics play a strong role in providing images of education to a young and impressionable readership. The Beano’s Bash Street Kids, for example, with their outrageous and anarchic classroom, are familiar to children in the UK. Japanese manga comics, generally aimed at a ‘youth’ market, have also become popular in the West and frequently incorporate school or college scenarios. A recent publishing success has been the manga series based on Battle Royale, the cult Japanese novel/film that depicts a future society where gangs of schoolchildren are made to fight to the death for entertainment. The cartoon genre, however, has increasingly moved from print-based comics to its animated form on television or in the cinema. Examples with significant educational representations include Beavis and Butthead (Fisher, 1997), Bromwell High, King of the Hill, The Simpsons (Kantor et al., 2001) and South Park.

The use of print cartoons in relation to an analysis of teachers’ professional identity has been discussed by Warburton and Saunders (1996). Using a semiotic approach based on Barthes (1964), they focus on the meanings of three cartoons representing teachers that appeared in the Daily Express and Daily Mail newspapers and contributed to the ‘Great Debate’ on education launched by Prime Minister James Callaghan’s influential speech at Ruskin College, Oxford, on 18 October 1976. Warburton and Saunders (1996, p. 308) argue that such cartoons act as ‘an indicator of public perception’ and constitute ‘evidence of myths and folklore, in the sense of publicly held stereotypes and “legends”’. The kind of cartoon animation represented by Beavis and Butt-head and The Simpsons, however, is markedly different to a ‘static’ newspaper cartoon in terms of how its messages are communicated, particularly if McLuhan’s (1964) comment that ‘the medium is the message’ is believed.

Television and radio

Television is now a twenty-four-hour and global medium; it is also digital and interactive. In the UK and the USA, popular programming other than reality TV and news broadcasts tends to concentrate on dramas and documentaries that focus on crime and medicine. Yet, while the education scenario is not as common as police or hospital-based productions, it is none the less a staple ...