![]()

1

THE LANGUAGES OF THE YIJING

AND THE REPRESENTATION

OF REALITY

Writing does not exhaust words, and words do not exhaust ideas … The Master [Confucius] said: “The sages established images [xiang] in order to express their ideas exhaustively. They established the hexagrams [gua] in order to treat exhaustively the true innate tendency of things and … they attached phrases [ci] to the hexagrams in order to exhaust what they had to say.”

(The “Great Commentary” (Dazhuan) of the Yijing)

Introduction

In traditional Chinese thought, the sixty-four hexagrams of the Yijing (Classic of Changes) represented symbolically the images or structures of change in the universe, and, as such, had enormous explanatory value. Like Chinese characters, these hexagrams were a distinctly visual medium of communication, concrete yet ambiguous, with several possible levels of meaning as well as a great many accumulated allusions and associations. As it developed over time, the Yijing reveals with striking clarity one of the most important ways that the Chinese in pre-twentieth-century China organized and explained the world around them. Through an analysis of the symbolism, structure, and cultural uses of the Changes, we can gain insights into deeply imbedded and long-standing Chinese patterns of perception, forms of logic, styles of argumentation, and approaches to questions of aesthetic and moral value.1

The basic structure of the Changes

The Changes first took shape about three thousand years ago as a divination manual, comprised of sixty-four six-line symbols known as hexagrams (gua). Each hexagram was uniquely constructed, distinguished from all the others by its combination of solid (_____ ) and/or “broken” ( _ _ ) lines (yao). The first two hexagrams in the conventional order are Qian and Kun; the remaining sixty-two hexagrams represent permutations of these two paradigmatic symbols:

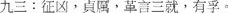

At some point in the Zhou dynasty (c. 1045–256 BCE), probably no later than the ninth or eighth century, each hexagram acquired a “hexagram name” (guaming) a brief written description known as a “judgment” (tuan or guaci; aka “decision” or “tag”) and a short explanatory text for each of its six lines called a “line statement” (yaoci).2

The hexagram name, which indicates its basic symbolic significance, refers generally to a thing, an activity, a state, a situation, a quality, an emotion, or a relationship, for example, “Well,” “Cauldron,” “Marrying Maid,” “Treading,” “Following,” “Viewing,” “Juvenile Ignorance,” “Peace,” “Obstruction,” “Waiting,” “Contention,” “Ills to be Cured,” “Modesty,”“Elegance,” “Great Strength,” “Contentment,” “Inner Trust,” “Joy,” “Closeness,” “Fellowship,” “Reciprocity,” etc.3 These are, however, rather conventional renderings of the terms. Much debate revolves around the earliest meanings of the hexagrams—especially since several alternative versions of the Changes have been discovered during the past four decades or so.4

The judgment of a hexagram provides certain kinds of advice, expressed in extremely cryptic language. Most judgments originally referred to ancient and now obscure divinatory formulas involving sacrifices and offerings to spirits.5 Here are a few representative examples: “Primary receipt, favorable to divine;” “The determination is favorable for a great man; no misfortune;” “Step on the tiger's tail; it won't bite the person; a sacrificial offering;” “Gather the people in the open country; a sacrificial offering; favorable for crossing a big river; a favorable determination for a noble person.”6

Line statements, which vary in length from as few as two characters to as many as thirty, often include records from previous divinations that were either transmitted orally or recorded in early divination manuals. Many of these statements seem to be based directly or indirectly on “omen verses” of the sort that can also be found on Shang dynasty oracle bones. Some examples:“In the hunt there is a catch: advantageous to shackle captives; no misfortune. The elder son leads the troops; the younger son carts the corpses; the determination is ominous;” “In crossing the river at the shallows he gets the top of his head wet: ominous; [but] no misfortune.”7

Taken together, the six lines of a hexagram represent a situation in time and space, a “field of action with multiple actors or factors,” all of which are in constant, dynamic play.8 These lines, reading from the bottom to the top, represent the evolution of the situation and/or the major players involved.The first, second and third lines comprise a “lower” trigram and the fourth, fifth and sixth lines constitute an “upper” trigram, each having its own set of symbolic attributes. Below, the eight trigrams with what may well have been their earliest primary meanings:

The operating assumption of the Yijing, as it developed over time, was that the sixty-four hexagrams represented all of the basic circumstances of change in the universe, and that by selecting a particular hexagram or hexagrams, and correctly interpreting the various symbolic elements of each, a person could gain insight into the patterns of cosmic change and devise a strategy for dealing with problems or uncertainties concerning the present and the future. Interpretation, whether undertaken for inspiration, general guidance, scholarly purposes or in the course of an actual divination, required a deep understanding of the relationship between the lines, the line statements, and the trigrams of the chosen hexagram, and often an appreciation of the way that the selected hexagram might be related to other hexagrams.9

To get a sense of the interpretative variables involved, as well as the rich metaphorical possibilities they offer, let us look briefly at the Ge hexagram, as it may have been understood in China around the eighth century BCE.10

[Constituent trigrams: below, Li (Fire); above, Dui (Lake)]

Judgment: On a sacrifice day, take/use captives. Grand offering. A favorable determination. Troubles disappear.

First nine [nine indicates a solid line]: Bind [them?] with the hide [ge] of a brown/yellow ox.

Second six [six indicates a divided line]: On a sacrifice day, make a change [ge]; auspicious for an attack; no misfortune.

Third nine: Ominous for an attack; the determination [of the divination] is threatening. A leather [ge] harness with three tassels; there will be captives.

Fourth nine: Trouble disappears; there will be a captive and a change of orders; auspicious.

Fifth nine: A great man performs a “tiger change;” there will be a capture [or captive(s)] before any divining is done.

Top six: The noble person performs a “leopard change;” the petty person wears rawhide [ge] on his face; ominous for an attack; auspicious in determining a dwelling.

As with most of the other sixty-three hexagrams, very little in the basic text of the Ge hexagram is unambiguously clear—even if we can reasonably assume that the basic theme of the hexagram seems to be warfare. The judgment and several of the line statements contain loan words (always tricky), and there are several possible meanings for the feline “transformations” mentioned in the last two line statements.

Obviously, then, commentaries were needed to make practical, moral and/or metaphysical sense out of cryptic texts of this sort. Over time, literally thousands of such commentaries were written on the Changes, reflecting nearly every conceivable political, social, philosophical and religious viewpoint.11 The most important of these commentaries, at least in the early history of the work, were known collectively as the “Ten Wings” (Shiyi).They became attached to the Yijing when the Changes received imperial sanction in 136 BCE as a major “Confucian” classic. One of the most important reasons for adding the Ten Wings to the basic text at this time was that they were widely (although erroneously) believed to have been written—or at least edited—by Confucius.12 Had it not been for this close association with the great Sage, we may doubt that Chinese scholars would have scrutinized the document so carefully and searched so relentlessly for its deeper significance over the next two thousand years or so.

The cosmology of the Changes

The Ten Wings articulated the Yijing's implicit cosmology and invested the classic with an alluring philosophical flavor and an attractive literary style. This amplified version of the Changes emphasized a fundamental unity between Heaven, Earth and Man, and it reflected a distinctive form of correlative logic that emerged in the late Zhou dynasty (c. 1050–256 BCE) and became a major feature of Chinese thought throughout the entire imperial era (206 BCE–1912 CE). Metaphysically speaking, this approach was based on the idea that things behave in certain ways not necessarily because of prior actions or the impulsions of other things, but rather because they “resonate” (ying) with other entities and forces in a complex network of associations and correspondences.13 Correlative cosmology of this sort encouraged the idea of mutually implicated “force fields,” identified by various specialized terms such as yin and yang, the “five agents” (wuxing; also translated as the five elements, phases, activities, processes, etc.), the eight trigrams, the ten heavenly stems (shi tiangan), the twelve earthly branches (shier dizhi), the twenty-four solar periods (ershisi qi), the twenty-eight lunar lodges (ershiba xiu) and, of course, the sixty-four hexagrams. These terms, discussed at greater length below and in two other essays, also came to be linked with specific numerical val...