![]()

1 Information and decision making

People need information to plan their work, meet their deadlines and achieve their goals. They need it to analyse problems and make decisions. Information is certainly not in short supply these days, but not all of it is useful or reliable. This first theme explores your needs for information and asks you to consider how they are served by the sources of information that are available to you.

In this theme you will:

♦ Consider the differences between data, information and knowledge

♦ Identify and evaluate the sources of information that you use

♦ Assess whether information flows effectively within your team and identify areas for improvement

♦ Analyse how effectively you use the Internet as an information source.

From data to information to knowledge and learning

H D Clifton (1990) wrote that ‘one man’s information is another man’s data’, and certainly the definitions are blurred. However, it is now generally agreed that ‘data’ is pure and unprocessed – facts and figures without any added interpretation or analysis. Depending on the context, data can be highly significant. Think of a cricket or football score, your name and address. Since it provides the raw material to build information, it also has to be accurate. Any inaccuracies within the initial raw data will magnify as they aggregate upwards, and will seriously corrupt the validity of any conclusions you draw from it or decisions you base upon it.

Data

In a business context, data is associated with the operational aspects of the business and its day-to-day running. As such, it is often entered into a system and stored in large quantities, for example payroll data and sales figures. Such input data goes to create a data ‘set’ – names and addresses for a mail-merge file, an index to an online product database. It has to be structured correctly – all systems have some kind of validation process to check for obvious technical errors and missing data. To be reliable, the content needs to be accurate, not simply in terms of the correct number and type of characters per data field, but what the data actually represents in terms of meaning. This needs human intervention. Another aspect that affects accuracy is where the data comes from. You may be able to check your own in-house sources – for example, for internally generated data such as the payroll – but have to depend on trust (or the reputation of the supplier) for data received from outside, for example customer credit card details.

Information

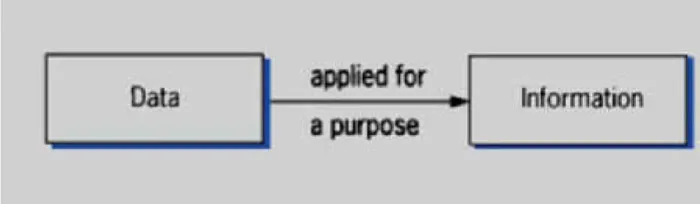

So how does ‘data’ (whether internal or external) become ‘information’? When it is applied to some purpose and is adding value which has meaning for the recipient, for example taking sets of sales figures (data) and producing a sales report on them (information).

Figure 1.1 From data to information

Of course, the same set of data can be used to produce different kinds of information, depending on how it is applied and who applies it. The same sales figures that you use to produce a market sector report might be used by someone else to justify adding to or reducing the size of the sales team. Such information can be used to manage a department, and for short and medium-term planning. Data can move to information and be turned to practical advantage very quickly – in 1815 the London Stock Market rapidly took advantage of the news brought by carrier pigeon of Wellington’s victory at Waterloo, which arrived two days before the human messenger arrived.

Information produced inside the organisation can be supplemented by a wealth of business information produced outside – market analyses, reports and case studies, for example.

Put briefly, information by itself is only of use if it is:

♦ the right information (fit for the purpose)

♦ at the right time

♦ in the right time

♦ at the right price.

Knowledge

Just as the words ‘data’ and ‘information’ are used interchangeably, there is considerable blurring and confusion between the terms ‘information’ and ‘knowledge’. It is helpful to think of knowledge as being of two types: the instinctive, subconscious, tacit or hidden knowledge, and the more formal, explicit or publicly available knowledge. An everyday example of these might be the knowledge that you use when driving a car (tacit), compared with the knowledge available from a driving manual or the Highway Code (explicit).

Theme 5 looks at knowledge in more detail and how it can be managed within organisations.

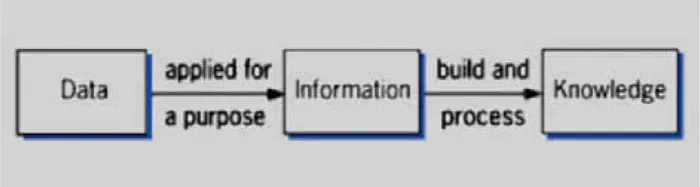

Figure 1.2 From data to information to knowledge

In a business context, knowledge is often linked to strategic levels of management and long-term business planning, where it is associated with having a head for business or business flair. However, knowledge vital to an organisation’s success can come from any level within it, and needs to be recognised as an important part of organisational assets. It combines information, experience and insight into a mix that is unique to every employee. It is this mix of understandings, based on personal knowledge at a tacit level, that creates the strengths and at times the vulnerability of organisations. It is important for organisations to recognise that holding knowledge at the tacit or hidden level can only have value where people are isolated from everyone else in their decision making. This is neither realistic nor good business practice.

Let’s sum up data-information-knowledge with an everyday example. Assume that you’re trying to decide on a specialist holiday for photography enthusiasts. Here, very broadly, are the stages you will go through:

Stage 1: collect lots of brochures on photography holidays. This is your basic data store.

Stage 2: work through the brochures, filtering out what you don’t want by applying your own criteria to them. Some will be in places you don’t want to go to, or at the wrong time of year, or the programmes may be at the wrong level of expertise (you may be looking for some advanced tuition, and many of the holidays are geared to beginners). You can now apply your information and make a decision on where to go on your holiday.

Stage 3: you go on your holiday and build your knowledge from testing your actual experience of the holiday against the information you had when you booked it. This knowledge (which you can use next time you want a similar holiday) can be kept to yourself (tacit) or you can share it by reporting back to your local photography club (explicit).

Capitalising on knowledge by making the tacit explicit, and identifying and managing the processes that nurture it, is a thread that runs through this book.

Building knowledge – learning

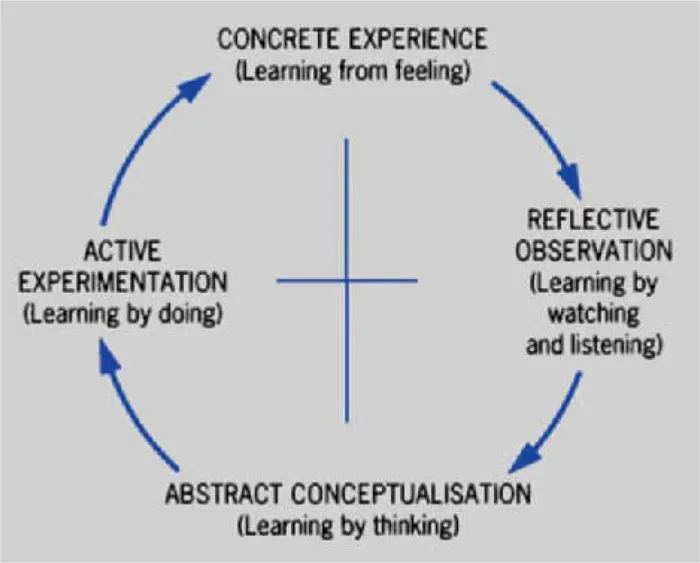

So how do we collect, process and build our knowledge? Kolb (1985) believes that there are four stages we all go through as part of the learning cycle:

♦ learning from feeling (through specific experience and relations with other people)

♦ learning by watching and listening (looking at things from different perspectives, observing carefully and reflecting before making judgements)

♦ learning by thinking (reflecting on and analysing ideas, drawing up mental maps and planning)

♦ learning by doing (getting things done, influencing other people, taking risks).

Figure 1.3 Kolb’s learning cycle

Source: Kolb (1985)

We all go through each of these processes to an extent, but different people feel more comfortable with some than with others. For example, an action-oriented person who likes to learn by doing may get very frustrated in a learning-by-watching situation or in one that requires reflection and analysis. It is useful for managers to be aware of their own and their staff’s learning styles, since these provide valuable insights into making...