eBook - ePub

Building a Prosperous Southeast Asia

Moving from Ersatz to Echt Capitalism

- 101 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Professor Yoshihara, an international expert on the Southeast Asian economies, looks beyond the causes of the current crisis to discuss what can be done to build a dynamic economy in Asia to ensure prosperity for the future. He takes the viewpoint that the only way to achieve this is to promote integration into the global economy through free trade and free capital movement. He puts forward a convincing argument that government intervention is not the way forward and has in fact helped cause the present crisis. But a prosperous future is possible, he argues, by renovating institutions and adapting new attitudes. A most timely book with lessons for other parts of the world as well as for Southeast Asia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Building a Prosperous Southeast Asia by Kunio Yoshihara in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Études ethniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Economic Crisis: How serious is it and how did it all begin?

The crisis

The economies of the ASEAN 4 (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand) are in bad shape in late 1998, This can be seen, for example, from the depressed condition of the automobile market. In 1996, about 1.4 million cars were sold. In 1997, the market was not too bad, although there was a 10 percent decline. But 1998 will record a further 65 percent decline. As a result, demand, estimated at 440,000 cars, will be about 30 percent of the peak level in 1996.

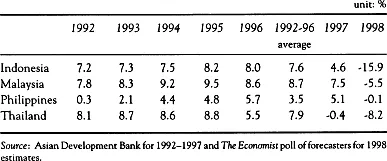

The IMF says that the ASEAN 4 will experience a 10 percent decline in GDP in 1998. This situation is a sea change from that of the five year period before 1997. As shown in Table 1, Indonesia recorded an average growth rate of 7.6 percent in the period; Malaysia, 8.7 percent; the Philippines, 3.5 percent; and Thailand, 7.9 percent. In the case of the Philippines, because of political instability in the post-Marcos period, it took some time for the economy to pick up. Eventually in the last half of President Ramos' administration, the economy grew at a rate of 5 percent. In 1996, it seemed that the Philippines finally caught up with the others in the growth game.

Among the ASEAN 4, the Indonesian economy will record the worst decline in 1998, about 16 percent decline (some forecast a 20 percent decline). The Malaysian and Thai economies will not be affected that much. But Malaysia will record a negative growth of 5.5 percent, and Thailand one of 8.2 percent. The Philippines is in best shape. It might be able to avoid a decline in

TABLE 1

Annual Growth Rates of GDP in the ASEAN 4, 1992–1998

Annual Growth Rates of GDP in the ASEAN 4, 1992–1998

Source: Asian Development Bank for 1992–1997 and The Economist poll of forecasters for 1998 estimates.

GDP, though the chances are that it will record a negative growth rate of 0.1 percent.

The financial sector, specially banks, are in even worse shape than the automobile industry. How bad the situation is can be seen from the large size of banks' nonperforming loans. The ratio of nonperforming to total loans is estimated to be about 60 percent for Indonesia, 35 percent for Thailand, 12 percent for Malaysia, and 11 percent for the Philippines. The banks may not have to write off all of their bad loans, but will have to write off a large percentage. Even if the banks have to write off only a third, they will become insolvent, because loans are much bigger (usually, more than 15 times) than equity capital. That is, if a bank's equity is one trillion rupiah and if it cannot get back 20 percent of a total of 15 trillion rupiah loans, the loss of 3 trillion rupiah (20 percent of 15 trillion rupiah) is bigger than its equity of one trillion rupiah. Usually, if the ratio of nonperforming loans exceeds 20 percent, the banking sector is in big trouble. In Japan, where the banking sector is also in trouble, the ratio is said to be about 11 percent. Even this magnitude is causing a big headache to Japanese bankers.

The ratio of nonperforming loans in the Philippines, according to the international rating agency Standard & Poor's, will rise to 20 percent in 1999. This is serious, but the situation will be worse in Malaysia. True, the ratio was not alarming in the middle of 1998 (in July, the published figure was about 12 percent), but Standard & Poor's says that the ratio of nonperforming loans will rise to about 30 percent in 1999. The major reason for the increase is that more loans will become uncollectable, but the other reason, which is technical, is that Standard & Poor's uses the international practice of judging loans as nonperforming if they are not serviced for three months. But the Malaysian central bank, in order to make the problem appear less serious, uses a six month past-due basis.

One reason why many companies in the ASEAN 4 are in trouble is that their currencies have lost much of their value. As shown in Table 2, the Indonesian rupiah lost 80 percent of its value between May 1997 and August 1998; the currencies of Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand, about 40 percent.

Many companies and banks in the ASEAN 4 borrowed heavily in dollars and used the money on projects which target the domestic markets. In Thailand, for example, since the exchange rate was stable over 10 years, many credit-worthy Thai companies borrowed money in dollars on the assumption that the exchange rate would remain the same. In Indonesia, the exchange rate was not so stable, but the rate of depreciation was gradual and therefore ‘predictable’. For example, if an Indonesian bank borrowed money in dollars and lent it to its customers in rupiah, it took into account the rate of depreciation when it decided on the rate of interest it charged for lending. The Malaysian ringgit was stable like the Thai baht. On the other hand, the Philippine peso had a more volatile history, similar to that of the Indonesian rupiah, but there was stability from the early 1990s. Either way, the foreign exchange risk was manageable; at least, the companies which could borrow in dollars thought so.

Suddenly in July 1997, a foreign exchange crisis began. It started first in Thailand, and then spread to the other three countries. The result was a big depreciation of their currencies. So, the banks which borrowed in dollars and lent in local currencies could not pay back to their foreign lenders, even if they managed to get back their local currency loans. The companies which borrowed directly from foreign lending institutions could not pay back, either,

TABLE 2

Economic Downturn in the ASEAN 4

Economic Downturn in the ASEAN 4

| May 1997 | August 1998 | ||

| Stock Prices | |||

| Indonesia | 100 | 59 | |

| Malaysia | 100 | 34 | |

| Philippines | 100 | 50 | |

| Thailand | 100 | 49 | |

| Exchange Rates | |||

| Indonesia | 100 | 20 | |

| Malaysia | 100 | 60 | |

| Philippines | 100 | 61 | |

| Thailand | 100 | 62 |

Source: Far Eastern Economic Review

because their revenues in local currencies were not enough. In Indonesia, for example, the companies needed five times as much revenues in rupiah as they did before in order to pay back the same amount of money they borrowed in dollars. In the other three countries, the situation was not so bad, but the companies needed 70 percent more revenues in local currencies. This was not possible for many companies in view of the depressed condition of their economies after the currency crisis.

This set off a vicious circle. Many of the companies which could not pay back the debts laid off their workers. The depositors with bankrupt financial institutions may not have lost their deposits, but cannot withdraw them to the full amount right away. The middle class people who invested in the stock market lost money with the crash of stock prices. As shown in Table 2, the stock prices in the ASEAN 4 declined 40 to 65 percent between May 1997 and August 1998. People felt rich when stock prices were higher, but now they feel depressed. The stock prices were already low in May 1997. They had been steadily declining since June 1996. In the following two year period, they declined about 80 percent. That is, in mid 1998, the stockholders were only 20 percent as rich as they had been two years earlier.

The ASEAN 4 are still in the middle of the crisis, and we do not know its full socio-economic consequences yet. In Thailand, many workers lost their jobs or are paid less, many children dropped out of school, and a large number of people go hungry. The situation is bad enough, but may get worse. The Malaysian situation is not as bad as the Thai, but it is likely to get worse in the near future. The political uncertainty created by the sacking of the former deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim and the capital control measures introduced in early September 1998 have created great uncertainty on the future of the Malaysian economy. The Philippines, possibly because it suffered enough in the 1980s and carried out painful reforms earlier, is in best shape. It is suffering from the global economic downturn, but it seems least affected by the after effect of the go-go years.

The Indonesian situation has been most serious. According to the World Bank, the incidence of poverty, which was down to 11 percent in 1995, at least doubled after the crisis began. The Indonesian government's statistics are more alarming. In the middle of 1998, the Indonesian government reports, about 50 percent of its population could not take 2100 calories a day, which is considered necessary for a healthy life.

The Indonesian situation is serious because it is accompanied by political crisis. The economic progress in the preceding three decades was directed by President Suharto, who ran the country like a personal fief. The trouble with that is that those who accumulated wealth under his rule did not win the approval of the people. They were Suharto's children and relatives, cronies and the Chinese. The first two got wealth by playing rigged games, whereas the Chinese, even if they gained wealth fairly are distrusted by large elements of the Muslim community on religious grounds. In May 1998, people went on to destroy all of them, including the President. Suharto was no longer acceptable to the politically active middle class, students and intellectuals because he was to blame for the economic difficulties they were suffering.

Much of the wealth of Suharto's children, relatives and cronies is yet to be confiscated, but the people who brought down President Suharto delivered a severe blow to the Chinese. During the May 1998 riots, about 5,000 Chinese stores were burned down or looted; 1,200 Chinese died; and at least 170 Chinese women were gang-raped. Prior to the riots and after, about 100,000 Chinese and US$60 billion of their capital fled the country. Since they controlled a large part of Indonesian business (many people say, 70 percent), the departure of the Chinese and their capital will make economic reconstruction difficult.

Thailand: the epicenter

For economists, the negative growth of Thai exports in 1996 was the most obvious indicator that something was wrong with the country. Thai exports expanded at a rate of 19 percent per year in the preceding four years. Since there was an acceleration in export growth, recording an average rate of 24 percent in 1994 and 1995, the negative growth of 1996 was a big surprise (see Table 3). Apparently, Thailand ceased to be attractive for export-oriented investors who were looking for cheap labor. The average hourly wage in Bangkok came close to US$3 per hour, which was about three times as high as in Shanghai.

Chinese competition, whose effect began to be felt more strongly after the devaluation of the yuan in 1994, affected all the ASEAN 4, but it was felt most strongly in Thailand. The Philippines was least affected, probably because its export potential which had been

| unit: percent | ||

| 1990 | 14.7 | |

| 1991 | 23.8 | |

| 1992 | 13.8 | |

| 1993 | 13.4 | |

| 1994 | 22.1 | |

| 1995 | 24.8 | |

| 1996 | −1.9 |

Source: Asian Development Bank

held back by the misrule of President Marcos began to improve under President Ramos and did not compare too unfavorably with China in industrial wages. In the other two, however, export growth declined to single digits in 1996 from a two-digit level of growth in the previous years.

Since Thailand was the most favored destination of export-oriented investors in the first few years of the 1990s, it had probably exhausted its initial advantage by the middle of the decade. If the country had been building its skills base smoothly, it would have continued to attract upper-scale investors, but it did not tackle the skills problem seriously. This does not mean, however, that there was no skills formation. It is just that it was not progressing fast enough to attract new types of investment and compensate for lost advantage in labor-intensive production.

The increased cost of production in Thailand was brought about by a large inflow of foreign capital. The trouble was not caused by the direct investment which had dominated the private capital inflow to the country by the early 1990s. True, a large inflow of Japanese direct investment from 1987 pushed up Thai industrial wages, but at least it contributed to export growth. But the loans from foreign financial institutions to Thai banks and companies, which increased from around 1991 when the country liberalized capital account transactions, began dominating the capital inflow in the mid 1990s. The money was used largely in the non-tradable sector (especially real estate development) and import substitution industries which could not compete in the international market (such as steel).

One can get a rough idea about how much of such capital came int...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contents

- 1 The Economic Crisis: How serious is it and how did it all begin?

- 2 Don't Think Retro!

- 3 Government Should Specialize and Strengthen

- 4 Reinventing Culture

- 5 Brave the Future