![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: Waves of Research

Morten T. Højsgaard and Margit Warburg

Our Sysop,

Who art On-Line,

High be thy clearance level.

Thy System up,

Thy Program executed

Off-line as it is on-line.

Give us this logon our database,

And allow our rants,

As we allow those who flame against us.

And do not access us to garbage,

But deliver us from outage.

For thine is the System and the Software and the Password forever.1

What does the Internet do to religion? How are religious experiences mediated online? In what ways have religious individuals and groups used and adapted to the emerging reality of virtual culture?

This book addresses some of the questions that can be raised about the various linkages between religion and cyberspace. It is based on the international conference on ‘Religion and Computer-Mediated Communication’ held at the University of Copenhagen in 2001, and the chapters of the book are selected from the many contributions to this symposium.

At the outset, the conference aimed at addressing three main, interrelated topics within the academic study of religion and cyberspace, and this is reflected in the organization of the book. Part I deals with the terminology, the epistemology, and the history of this field of research. Part II covers various aspects and transformations of religious authority and conflict in the age of the Internet, and Part III contains analyses of religious identity constructions and group formation dynamics within the online settings of cyberspace.

The first studies of religion and the Internet appeared in the mid-1990s, and the very novelty and potential of the subject were grasped with enthusiasm, resulting in what can now be seen as the first wave of research (Kinney 1995; Lochhead 1997; O’Leary 1996; Zaleski 1997). Representing a ‘second wave’ of research on religious communication online (MacWilliams 2002) , an important aim of this book is to document and discuss what kind of knowledge we actually have about the religious usage of the Internet. The far-reaching consequences predicted in the first wave will probably not all come true. However, now that the phenomenon of religious communication in cyberspace, on the Internet, or through computer-mediated communication systems has been with us for some years, new insight should be gained by researching the subject again. The conference, which is the basis for the book, proved that a range of scholars in the field agreed that the time was ripe for a revisit.

Stephen D. O’Leary – a scholar of religion and communication who started the ‘first wave’ of religious studies related to the Internet – in this book reassesses and evaluates the ideas of his earlier works in the light of the present situation. Having had an optimistic approach in his earlier writings, O’Leary admits that his present analyses of religion and cyberspace tend to have a pessimistic tone. Still, he maintains the basic evaluation of computer-mediated communication as something that ‘represents a cultural shift comparable in magnitude to the Gutenberg revolution’.

In the words of Lorne L. Dawson in his chapter, the ‘interactive potential of computer mediated communication gives it an advantage in mediating religious experience over conventional broadcast media’. Commenting on cyberspace and the new global communication networks as a whole, Eileen Barker in her chapter of the book declares that any ‘student of religion – or, indeed, of contemporary society – will ignore this new variable at his or her peril’. Pondering over her warning, the editors hope that this book may mean that any clever student of contemporary religion will be wise enough not to ignore the Internet!

Even the Taliban Used the Internet

When the Internet was first set up in 1969, it was primarily used for educational and military purposes, and it could not yet qualify as a public sphere as such. However, as the Internet was supplied with a more user-friendly graphical interface and began to grow significantly in the beginning of the 1990s, the religious usage of the new medium also started escalating.

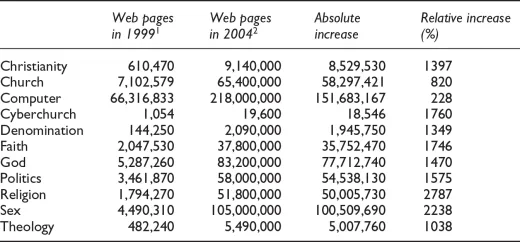

By the end of the 1990s there were more than 1.7 million web pages covering religion. In comparison there were slightly fewer than 5 million web pages containing the word sex on the Internet in 1999 (see table 1.1). By 2004, the number of religious web pages had grown considerably worldwide. There were then approximately 51 million pages on religion, 65 million web pages dealing with churches, and 83 million web pages containing the word God. As shown in table 1.1, at the same time there were 218 million, 105 million, and 58 million Internet pages containing the words computer, sex and politics, respectively.

Table 1.1 The number of religious web pages in 1999 and 2004

Notes

1 The search was conducted via http://www.altavista.digital.com on 24 May 1999 (Højsgaard 1999: 59).

2 The search was conducted via http://www.altavista.com on 16 November 2004.

If these numbers and their growth are indicative of the priorities of human desires in the age of digital information, religion is doing quite well! Surveys made by the Pew Internet and American Life project indicate that – although religion is not the most popular issue of cyberspace – the interest in this subject area among Internet users has become widespread: in 2001 28 million Americans had used the Internet for religious purposes (Larsen 2001). By 2004 the number of persons in the USA who had done things online relating to religious or spiritual matters had grown to almost 82 million (Hoover, Schofield Clark, and Rainie 2004).

Eileen Barker begins her chapter by addressing this remarkable historical change:

When, in 1995, Jean-François Mayer and I edited a special issue of Social Compass devoted to changes in new religions, there was not a single mention of the Internet or the Web. The nearest approximation to the subject was a chance remark I made about the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) having a sophisticated electronic network that could connect devotees throughout the world . . . Indeed, it was at the ISKCON communications centre in Sweden that I had first set eyes on the Internet, and, although I was impressed by the medium’s capacity to enable instant contact with fellow devotees throughout the world, it was at least a year later before something of the full import of this new phenomenon really began to dawn on me.

Today, almost every contemporary religious group is present on the Internet. Even the former Taliban regime in Afghanistan had its connections to this global communication network. Officially, the Taliban had forbidden the use of the Internet. However, in 2001 the foreign minister of the Taliban admitted that they were not against the Internet as such, only against what he perceived as ‘obscene, immoral and anti-Islamic material’ including sex and politics, which lurked ‘out there’. The Taliban therefore sought to establish a control system to guard against such material. They knew that controlling access to the unofficial information and uncensored communication possibilities of the Internet was crucial, as it would give all kinds of opportunities to bypass further control of whom you communicate with and what kind of information you send or retrieve.

Having observed various religious communication activities on the Internet for several years, Anastasia Karaflogka (2002: 287–288) documented that while in 1996–1997 there were 865 Internet pages on the Taliban, by the end of 2001 that number had grown to 329,000 pages. This increase, of course, should be seen in the light of the terror acts of 11 September 2001 in New York and Washington. The extraordinarily high growth rate of the material on this particular issue reflects the inevitable rise of attention and interest in the world public during this period. Likewise, other types of religious information and even ways of using the Internet as such have altered over the years as technology, political affairs, and migration patterns have changed. Some of these changes are documented in the pages of this book. Mia Lövheim and Alf Linderman’s call for ‘more longitudinal studies’ is, indeed, still topical.

Also reflecting the constant evolution of interconnections among religious and electronic networks, Mun-Cho Kim in his chapter sets up a historical model of the various steps that an information society may go through. His model starts with the basic computerization stage. It then goes on to the networking stage. It continues with a flexibility stage, and ends up in a cyber-stage (see fig. 9.1). The networking stage may have begun in 1995, which – according to Manuel Castells (2001: 3) among others – was, indeed, ‘the first year of widespread use of the world wide web’. The final cyber-stage, however, is a digitally embedded point that has not yet been reached (and probably never will be).

Addressing his own earlier writings on religion and cyberspace, Stephen D. O’Leary, as indicated above, admits that some of his ideas and attitudes towards the idea of cyberspace as a focal sacred space of the information society have changed over the years. ‘Though I do have some positive thoughts and hopes on this topic,’ he says, ‘I will not apologize if, on balance, I [now] seem to espouse cyber-pessimism. In the light of the terror attacks of the past few years, I have found it difficult to maintain the optimistic tone of my earlier writings. In many ways, I now see my early essays as naive and even utopian.’ In 1995 O’Leary thought that the Internet in just a few years would provide a positive and widely used way of experiencing and performing religion. In this book, O’Leary – though still convinced of its importance – expresses doubts about the effects and coverage of the Internet. In the age of digital information, people will still want to meet each other for religious purposes in face-to-face settings. Despite its various virtual representations in cyberspace, the physical Jerusalem, argues O’Leary, will maintain its importance as a holy place and corporeal point of political strife. Besides being a virtual platform for new kinds of religious communication genres, the Internet is also functioning as a supplement to or just a reflection of religion in the modern or postmodern society at large.

If the first wave of religious usage and academic studies of the Internet was filled with either utopian fascination or dystopian anxieties about the surreal potentials of the new digital communication medium, the second wave, in general, tends to be more reflexive and less unrealistic, as it seeks to come to terms with the technological differences, the communication contexts, and the overall transformations of the late modern society. In her doctoral dissertation Mia Lövheim (2004: 267) concludes that uncritical claims about the Internet as something ‘new’ and separate from other processes in society need to be questioned. Massimo Introvigne, writing for this volume, asserts that while ‘celebrations of the Internet as a new and more democratic approach to information were probably premature, dystrophic perspectives of manipulated Internet hierarchies subverting offline hierarchies, destroying responsibility and accountability in the process, need not necessarily prevail’. Common ground for Lövheim and Introvigne – both representing the second wave of research on religious online interaction in this respect – is their shared interest in avoiding either utopian or dystopian extremes in their assessment of the research field. Rather they attempt to focus on the factually situated practice of religious online interaction.

Cyberspace and Religion in Interaction

Buzzwords without obvious reference to situated practices in general flourish within the literature and the public debate on the Internet and the interactive cultures it has fostered. The culture of cyberspace, for instance, has been characterized by various authors and commentators during the last three or four years by such words and phrases as ‘global’, ‘democratic’, ‘anti-hierarchical’, ‘fluctuating’, ‘dynamic’, ‘user-oriented’, ‘virtual’, ‘visual’, ‘hyper-textual’, ‘inter-textual’, ‘converging’, and ‘discursive’. The various information and communication technologies that are part of the Internet likewise have been called ‘symbols of a new world economy’, ‘voices or mediums of the grass roots’, ‘reflections of the rise of the network society’, ‘expressions of the renaissance of oral culture’, ‘the missing link between modern and postmodern mindsets’, ‘multi-pattern services’, ‘steps towards a possible future generation of artificial intelligences’, and ‘interfaces of human-to-human or human-to-machine dialogue’.

One of the most prevalent ideas that permeate these catchy descriptions of cyber culture is the notion of interactivity or interaction. Accordingly, this book seeks to investigate how a range of all these interactive practices and ideas of interaction in cyberspace are situated, constructed, and related theoretically as well as empirically to the field of religion.

As Mark Poster (1995) has summarily pointed out, the Internet by and large can be used either as a television set or as a telephone. In the first case, the Internet transmits messages, religious or not, from content provider(s) to content consumer(s). In the second case, the Internet connects people from various places. Given the specific focus on interactivity and interaction that goes through much literature on cyber culture, this latter way of perceiving the Internet also constitutes a special concern of the book. The perception of the Internet as a telephone is not only about connections; it is, of course, also about conversational applications, multi-faceted interactions, networks, individual usages and group formations.

Mun-Cho Kim in this book defines the Internet as a medium with great privacy, a focused audience, multi-way direction, and variable temporality. Along with Mark Poster, Kim thus depicts the Internet as being in clear opposition to the mainstream usage or perception of the television set as a medium with low privacy, a broad audience, one-way direction, and delayed temporality (see table 8.1). Mia Lövheim and Alf Linderman, in their chapter on identity formation in cyberspace, add further insights to the understanding of the Internet as a medium that facilitates multi-directed connections rather than one-way transmissions. They use the terms information exchange, interactivity, and interdependence to describe some of the most important aspects or facets that must be taken into consideration before evaluating the religious impact of the Internet. Information exchange is the category they consider the most basic form of connection in this r...