1 The East Asian crisis

Ross Garnaut

INTRODUCTION

There never was such a thing as an East Asian ‘miracle’. There was, however, an East Asian phenomenon of sustained rapid growth, as one economy after another in East Asia began to accumulate capital, apply improved technology, and utilise human resources more effectively for economic development.

Through the 1990s the international community came to expect the continuation of sustained, rapid growth in the developing economies of East Asia. These expectations were shattered by the sudden emergence of financial, economic and even political disruption throughout the region in the second half of 1997. This book documents the evolution of the East Asian crisis, and seeks to answer some big questions raised by this dramatic episode.

What were the causes? What sense can be made of the coincidence in timing of the onset of crisis in many countries and, in particular, of the phenomenon that came to be described as ‘contagion’? Why did the crisis first appear in Thailand, and have its most costly expression in Indonesia? How did some economies with close ties with the most troubled countries avoid severe consequences from the East Asian crisis, at least through its first year? How was the evolution of crisis in each country affected by the character of the financial system and its regulatory framework?

A second set of issues involves the immediate policy response to the crisis. How much was the path and eventual severity of the crisis affected, ameliorated or exacerbated by the policy responses in individual economies? And how were they affected by the international policy response – in particular, by the IMF-led programs in Thailand, Indonesia and Korea?

Finally, the volume seeks to draw lessons from this remarkable and unhappy episode. How are short- and long-run growth prospects affected? Does the crisis mark the end of sustained rapid growth in East Asia, or in individual economies in which it had appeared well established? What have we learned about the relative merits of various types of exchange rate regimes, and about macroeconomic management more broadly in rapidly growing and increasingly outward-oriented economies? About the priority of liberalisation of capital flows in the sequence of related reforms? About the type of financial systems and regulatory regimes that are most helpful to sustaining growth in economies becoming deeply integrated into the international economy? About domestic and international policy adjustments that can contribute to avoiding financial crises in the future? Most fundamentally, how does the crisis of 1997–8 affect thought about economic development and economic policy in East Asia and beyond?

STRUCTURE OF THE BOOK

This introductory chapter sketches some of the main features of the crisis, its origins and its evolution, and some preliminary thoughts about its implications for policy and development. It summarises some basic economic data for the 13 economies covered in the case study chapters that comprise Parts II to IV, for purposes of comparison and easy reference. And it begins to address questions that are dealt with in detail in subsequent chapters.

The core of this book, and its distinctive feature, is the set of twelve chapters in the form of country case studies. Four of these concern the economies that have been most troubled by the crisis (Part II). Why did the crisis first appear in Thailand? Why was it so severe in Malaysia and Korea – economies apparently with great underlying strength? And why did Indonesia – at first appearing to have the least problematic macroeconomic fundamentals of the troubled four – experience the greatest and least tractable damage?

In Part III the Vietnam case study raises the question of whether the absence of convertibility on the capital account was a help in avoiding contagion. Perhaps more importantly, it discusses the conditions under which Vietnam might have benefited from more openness to capital flows, while keeping the risk of financial instability to a manageable level. Vietnam’s huge current account deficit raises a question about whether capital account controls have simply enabled necessary adjustments to be postponed. China also administers heavy controls on capital movements, but this is rendered less central to China’s story by a strong current account and high foreign exchange reserves, price stability, massive direct foreign investment inflows, and a well-established reform momentum.

The chapter on India provides another perspective on capital controls. This country is linked less closely to East Asian trade and investment than any of the East Asians themselves, but may be exposed to ‘contagion’ through competition with East Asian economies in global markets, and through the pulling back of Western investors from Asia as a whole. Here the questions include why India and other South Asian economies appear to have been able to withstand the growth-depressing effects of the crisis, and whether this may turn out to be a temporary respite.

The five other case studies, in Part IV, examine six economies that, so far, have avoided exceptionally large set-backs to economic growth. The Philippines, long the ‘sick man’ of Southeast Asia, weathered initial shocks comparable to those felt by Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia far more successfully. Taiwan in one chapter, and Singapore and Hong Kong together in another, provide additional examples of very open economies, closely linked to the troubled four and receiving large initial shocks from them, but which nevertheless had avoided financial crisis up until June 1998. Examination of these important cases leads into an examination of the value to sustainable economic growth of relatively transparent regulatory regimes and competitive, open financial systems. The treatment of Singapore and Hong Kong within a single chapter also allows comparison of the effects of highly contrasting exchange rate regimes – the former, a managed float; the latter, a rate firmly fixed against the US dollar and incorporating major elements of a currency board system.

Australia is in some ways similar to Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore, and in other ways different. Far-reaching financial deregulation in the mid-1980s abolished capital controls, floated the currency, removed direct controls on interest rates and lending, and increased the level of competition between banks and amongst financial institutions more generally. By the time of the East Asian crisis, financial institutions and regulatory authorities had learned how to make the new arrangements work – not least through the bitter lessons from Australia’s own currency crisis of 1985 and 1986, and the banking crisis it experienced in the early 1990s. The Australia chapter asks whether there were lessons in the currency and banking instability in the eight years following financial deregulation that, if heeded by the East Asian developing economies, might have helped them to avoid the worst of the current crisis.

The case study of Japan describes a country that had been having its own, slowburning financial problems for some years before the East Asian crisis began, and in which some of the same contributory factors are evident – such as a boom-and-bust cycle in asset markets, and weakness in the financial system and its regulatory regime. The decline of the yen has been gentle by comparison with that of the currencies of the troubled four, although in total magnitude over the three years to mid-1998 it is about as large as that of the baht, ringgit and won. At the heart of the Japanese stagnation is weakness in the banking system – the focus of this chapter – and there are lessons in the Japanese experience for financial reform in developing East Asia. The Japanese case is important, moreover, because Japan’s dominant role in regional trade and capital flows meant that its own slow growth and currency weakness helped it to trigger the East Asian crisis, and now adds to the difficulty of recovery in the region.

Eight other chapters in Parts V, VI and VII step back from the country detail to analyse more general issues and to draw more general conclusions.

Warwick McKibbin applies a dynamic intertemporal general equilibrium model to simulate the East Asian crisis, focusing on the impact of a sudden increase in the perceived risk of holding assets in the countries of the region. He emphasises the importance of taking into consideration the changes in international capital flows that necessarily accompany – indeed, drive – changes in the pattern of international trade, rather than simply assuming that it is possible to estimate the impact on trade flows resulting from the observed realignments of exchange rates without doing so.

David Nellor describes the policy reform packages that were negotiated as a condition of International Monetary Fund (IMF) financial support for three of the troubled economies – Thailand, Indonesia and Korea – and the rationale for their various components. There has been extensive criticism of the IMF’s approach, especially in Indonesia, against which a vigorous defence is presented in this chapter.

David Hale compares the Mexican crisis of 1994 with the East Asian crises. The latter are distinguished by financial excess and miscalculation within the private sector rather than the public sector. This required different domestic and international policy responses – a lesson that was learned late, and imperfectly, in East Asia. The Mexican economy recovered quickly and strongly from 1995. Hale examines the conditions under which East Asian economies might enjoy a similarly impressive return to good health.

George Fane looks at the roles that weaknesses in the financial system and in prudential regulation have played in the crisis. He points out the near impossibility of persuading depositors that governments will not bail them out if banks fail, and argues that this implies that a moral hazard problem is therefore unavoidable. The important need, then, is to adopt policies that will optimally reduce and offset problems of this kind.

Alan Walters examines the choice of exchange rate regimes in the light of the recent experience. The hybrid regimes that were present in the four troubled economies – with a fixed but adjustable peg against the US dollar – contributed to the emergence of financial crisis. This raises an old question: whether genuinely fixed and freely floating rates are more conducive to stability than the hybrids in between.

Hadi Soesastro looks beyond the immediate issue of restoring financial stability and economic growth to focus on what is likely to be the most important legacy of the East Asian crisis – namely, the changes in ideas about development-oriented economic policy it will stimulate. He examines the lessons to be drawn, and the changes in perceptions that are likely to result, from the crisis, and asks what effects these are likely to have on the future path of development.

Finally, McLeod draws upon the book as a whole in his discussion of the new era of financial fragility, and Garnaut looks at economic lessons from the crisis.

The remainder of this introductory chapter sketches important features of the East Asian crisis, and provides statistical reference points for the case study chapters that follow.

EAST ASIAN ECONOMIES ARE NOT ALL ALIKE

The East Asian economies in their years of sustained high growth seemed to have much in common, at least to distant observers. The World Bank’s East Asian Miracle (1993) drew attention to common features contributing to growth across economies as diverse as Korea, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand. The common features were said to include high rates of saving and investment, a strong focus on investment in education, sound macroeconomic policy generating reasonably stable macroeconomic conditions, and good economic governance.

In the unhappy times since mid-1997, differences have been more obvious than similarities. In the ‘contagion’ that followed Thailand’s abandonment of the dollar peg, domestic and international financial markets raised the risk premia on investment throughout developing East Asia. A largely undifferentiated initial shock had extraordinarily different effects, depending crucially on the nature of political systems, policy responses and financial institutions in the countries concerned.

While the expression ‘Asian financial crisis’ appeared frequently in the world’s newspaper headlines in the third quarter of 1997, at that time it was a misnomer. Then, it would have been more accurate to confine the term ‘financial crisis’ to Indonesia, Korea, Thailand and Malaysia. There had been virtually no ‘crisis’ in South Asia. A number of the other economies in East Asia – the Philippines, Singapore, China and, more problematically, Hong Kong – were expected to grow in 1998 and 1999 at rates below the average of recent years, but well within the range of their own experience over the past two decades. Through 1998, however, economic contraction, currency depreciation and reduction in imports in some major economies have been transmitted to others. Social disorder and political instability in Indonesia in May, and the realisation that Japan was in recession in June, sent new negative shocks through the region, generating intensive international discussion as it became clear that widespread economic recession through East Asia and beyond was a real possibility.

Still, by June 1998, there were only four countries in which serious economic dislocation had occurred, markedly more damaging than any since the beginning of the era of rapid, internationally-oriented growth. These countries contain about one-tenth of Asia’s population and one-sixth of East Asia’s. The one-tenth and the one-sixth matter a great deal. And for the 200 million people of Indonesia, the proliferating problems are of immeasurable consequence. Other countries and people remain vulnerable to further complications from the forces tending to recession unleashed in the first year of the crisis.

A STATISTICAL SKETCH OF THE CRISIS

This section presents a statistical sketch of macroeconomic conditions in the years preceding the crisis in each of the economies covered in case studies, to introduce the data, and for convenient reference throughout the book.

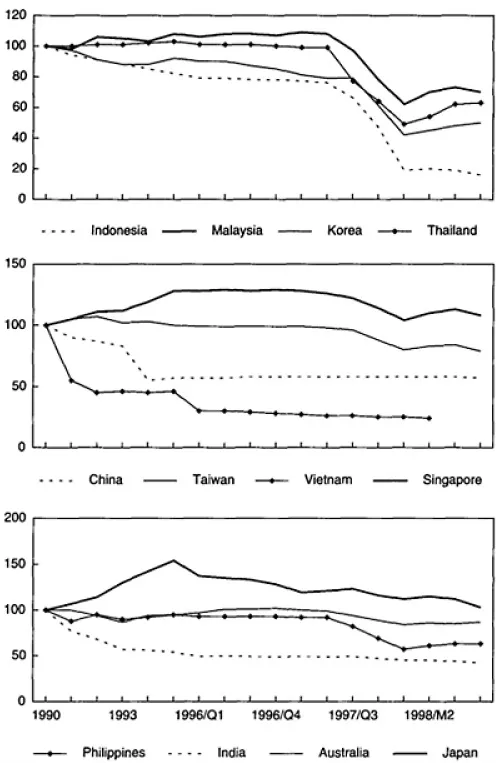

The first manifestation of crisis was in exchange rate movements (Figure 1.1). Indonesia stands out as having experienced by far the greatest fall in the value of its currency since mid-1997. At the other extreme, China, Vietnam, India and Hong Kong have seen little or no change in their exchange rates during the crisis period. Taking a longer-term perspective, it can be noted that all of this group other than Hong Kong had devalued their currencies by large amounts during the early and mid-1990s (although, in China’s case, the devaluation of the official exchange rate was in the context of unification of official and market rates that had little effect on the prices at which the majority of foreign trade was transacted). Of the remainder, Thailand, Malaysia and Korea have been hard hit; the Philippines, Taiwan, Australia and Singapore less so. The currencies of most of this group bounced back quite strongly during March and April 1998, but weakened again in May and June as a result of the political turmoil in Indonesia and the increasingly obvious weakness of Japan’s economy.

As we examine the other macroeconomic data, we learn to be wary of simple generalisations across the troubled economies and the others in our case studies. There are some general patterns linking macroeconomic conditions to the crisis. But they are complex, depending on the interaction between general economic factors, weaknesses in financial institutions, and policy and political responses.

The troubled economies had all grown rapidly at rates of the order of 8% per annum for several years prior to the crisis (Table 1.1). (The tables for Chapter 1 are collected at the end of the chapter, on pages 22–7.) Growth throughout East Asia other than the three Chinese economies was especially strong in 1995. Inflation at 3.5–6.5% per annum in the troubled economies in 1996 was not in itself an obvious precursor to crisis, but the persistence of rates above the contemporary international norm posed problems for economies with exchange rates pegged to a US dollar that was appreciating strongly against most other currencies (Table 1.2). A strong nominal exchange rate and inflation above international levels led to a significant appreciation of the real exchange rate through most of the East Asian developing economies after 1995, and notably in what became the troubled economies.

A severe slowdown in export growth in 1996 was experienced by most of East Asia. This was most apparent in Japan, Thailand, Korea and Malaysia, but was far less prominent in the fourth troubled country, Indonesia (Table 1.3). The Philippines, Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan and India all experienced significant reductions in export growth in the same year. Import growth declined in most East Asian countries (Table 1.4). Notably, Japan’s imports grew by only 3% in 1996, compared with 22% in the previous year.

Figure 1.1 Nominal US$ exchange rate (1990 = 100)

Note: Data are period averages, except for the last point, which is for 29 May 1998. The exchange rate is expressed as US$ per local currency. Hong Kong is not included in Figure 1.1 because there was virtually no change in its exchange rate during this period.

Source: IMF 1998d; IEDB, ANU. Data for Taiwan are from CEPD (various years). Data for Vietnam are from APEG 1998.

The troubled economies had relatively large current account deficits in the two years prior to the crisis (Table 1.5). Thailand became famous for its average deficit of around 7% of GDP in the first half of the 1990s, rising to 8% in 1995–6. Malaysia’s current account deficit soared to over 10% of GDP in 1995 before falling back to about 5% in 1996, a little lower than the average for the p...