- 330 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Foundations for A Psychology of Education

About this book

The chapters in this collection illustrate how current concepts and principles from various disciplines can be viewed from the perspective of their value to educational process thinking. While not providing specific prescriptions for educational problems, the articles provide relevant experimental and theoretical knowledge has accumulated in many fields including learning theory, cognitive development, motivation, and intellectual abilities and attitudes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Foundations for A Psychology of Education by Alan M. Lesgold,Robert Glaser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education General1 |

Learning Theory

The principal output of the first century of research and theory on human learning and memory has been a massive accumulation of experimental and observational facts about learning in various simple, standardized tasks (most often remote from situations of practical relevance) and a number of limited generalizations, some perhaps deserving to be termed empirical laws, that organize and describe segments of this factual output. One can readily understand impatience with the slow pace of development of the intellectual tools we need to analyze important kinds of school learning and instruction. Nonetheless, making use of the tools now at hand can already be of value in the interpretation of research and the establishment of connections between research and practice. Further, vigorous attempts to make use of current theories outside the laboratory can contribute to their continuing refinement and elaboration (Baddeley, 1982). These thoughts have led to the orientation of this chapter toward a focus on the more general concepts and principles of learning now at hand.1

The aspects of learning theory to be reviewed here are dictated by potential applicability to problems of education. Thus it is sensible to start by classifying the products of education in terms of what is learned. Some principal categories are the following: (a) habits and skills, including habits of seeking and using information and skills of reading, calculating, communicating, and problem solving; (b) attitudes and values; (c) knowledge, which may be sub-classified in terms of basic concepts and procedures at the first level and organized assemblages of factual knowledge at higher levels; and (d) understanding, including understanding the nature of one's self, of mankind in general, of society, and of the natural world.

A prime task of education is to supply the necessary materials and to arrange experiences for students that will lead to these kinds of learning. However, the learning is not automatic and in fact often fails. Thus, it is important to understand the learning process, what factors are important, why things often go wrong. Resources available for the task are of rather different kinds. Perhaps the most basic are the theoretical foundations of learning and instructional theory, which underlie our ability to analyze and diagnose educational problems and to guide applied research. At a more directly practical level are the knowledge and expertise about the conduct of education, drawn from practical experience and from research in educational settings.

This chapter is concerned primarily with theoretical foundations. Thus, the ideas discussed are necessarily largely abstract and removed from specific educational situations. Where possible I point out connections between abstract principles and specific problems, but for the most part these connections are developed in other chapters of this book.

The overall organization of the chapter is as follows. First, I consider the nature of the mental apparatus that accomplishes learning, characterizing its structures and processes in terms of contemporary research and theory. Next, the chapter examines the varieties of learning implicated in the formation of habits, skills, and attitudes. Third, processes basic to the acquisition of knowledge are examined.

THE INFORMATION-PROCESSING SYSTEM

In the course of any school session, a student encounters many episodes in which he or she hears or reads a message presenting some facts or concepts about the topic under study. The results of this potential learning experience may vary widely depending on circumstances. Suppose, for example, that a learning episode consisted in the presentation of a segment of film strip showing a famous person delivering some memorable speech. Typically, a student who had observed the film would recognize the episode if the same film strip were shown again, even after an interval of days or weeks. But if the student were asked to recall the episode, the result would strongly depend on a number of conditions. On an immediate test, the student would probably remember much of the episode, including even specific words, although some details would evidently not have registered at all. After a longer interval, the result might be only recall for the gist of the speech or might include scattered excerpts of the actual text depending on various aspects of the learner's approach to the task.

In general, whether information is presented via films, lectures, readings, or other kinds of experiences, the process of adding the information to the stock of knowledge and skill in the mind of the student in usable form is complex and subject to many uncertainties. The purpose of this section is to sketch in outline the modal current view as to how the memory system is organized and how it is utilized by way of the mental operations that determine whether and how information is stored and retrieved.

Organization of Memory

On one point, virtually all current investigators are agreed: Memory is not all of a piece, like such repositories as cupboards or warehouses, but comprises at a minimum several major subsystems. Some aspects of the organization of memory can be anticipated from a consideration of the ways in which it must contribute to various cognitive activities and the constraints under which it must operate.

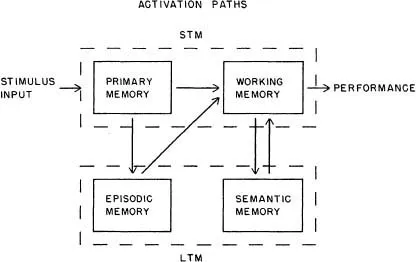

The most basic constraint is that mental processes take time, and, in fact, are very slow in comparison to the operation of a computer. The time required for a single elementary cognitive operation, such as comparing a printed letter with its representation in memory, is of the order of 25–50 milliseconds (Sternberg, 1966), and the time needed to retrieve an item of information from memory is considerably longer (Estes, 1980). A second constraint, deriving from the first, is that, to be useful, information in memory must be organized for retrieval. A sequential record of all the experiences a child has had in school, for example, could contribute almost nothing to any constructive activity such as problem solving because it would take too long to locate needed information by searching the record. Information taken in via the senses must be sifted, classified, and entered in memory in a way that makes recovery reasonably efficient. To make this objective achievable, it appears essential that one's memory include at least the subsystems sketched in Fig. 1.1.

FIG. 1.1. Schematization of the flow of information through subsystems of short-term (STM) and long-term (LTM) memory (from Estes, 1982a, Fig.4.2, reprinted by permission of Cambridge University Press).

Primary Memory. Traditionally defined as a mental image, or representation, of perceived events that has not yet faded from awareness (James, 1890), primary memory is an essential first stage in the processing system, for intelligent filtering and selection of information is possible only if there is available a temporary record of all that has been perceived. Primary memory is necessarily transient because its contents must be continually displaced by new incoming information, but information currently in primary memory is not necessarily wiped out all of a piece. If some aspects of a perceptual experience generate activity in emotional or motivational systems, these tend to be consolidated and preserved in secondary, or long-term, memory.

Primary memory is presumed to be passive and unselective. Hence, in any situation involving some kind of problem solving or other purposeful activity, it is essential that information in primary memory whose value or relevance is not immediately apparent be transferred to a system where it can undergo further processing, whereas primary memory is freed for new inputs.

Working Memory. As a consequence of task requirements, or sometimes simply long-term strategies or habits, the individual sets criteria for the types of items that are selected for passage from primary memory into the limited-capacity system termed the rehearsal buffer (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968) or working memory (Baddeley, 1976). Here, representations of items or events, usually encoded in a more abstract form than initially perceived, can be kept in an active state by rehearsal and are subject to cognitive operations such as search and comparison. The capacity of working memory is assumed ordinarily to be only a few items (Miller, 1956), but it is expandable by appropriate practice (Chase & Ericsson, 1981). The importance of this system for education is that it serves as an entryway to long-term memory, at least for verbal material (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968; Baddeley, 1976; Bower, 1975: Newell, 1973). Also, the setting or modification of selection criteria for entry of material into working memory appears to be the earliest point in information processing at which motivation influences learning.

Long-Term Memory. The long-term system is assumed to be of unlimited capacity, including all of the stored information that is retained more than a few seconds, and provides the basis for learned skills and knowledge. Several subsystems are distinguished on criteria of content and function. Procedural memory, not represented in Fig. 1.1, is the assemblage of stored action routines that constitute skills and habits. The storage of procedural information (effectively, stimulus-response associations, or condition-action pairs) evidently need not involve working memory, and the stored procedural information is not necessarily accessible to awareness or verbal report (Anderson, 1983; Tulving, 1983). The episodic system comprises memories of events in their temporal and situational contexts, whereas the semantic (alternatively termed categorical or declarative)system includes memory representations that are generally independent of context, for example, meanings, facts, and rules (Tulving, 1968, 1983). In a typical educational situation, the episodic system might include one's memory that one heard particular words or sentences in a lecture given on a specific occasion, whereas semantic memory would accumulate more abstract information having to do, for example, with the meanings of the words and the type of information communicated.

Presumably, most learning that occurs in educational settings has to do with semantic memory and has a cumulative character as distinguished from the memory for discrete events that characterizes episodic memory. Episodic memory appears to enter educational learning mainly as a stage or component in more complex processes, as, for example, memory for particular exemplars of categories in concept learning or memory for the outcomes of particular actions in skill learning. The organized knowledge that accumulates from such experiences need not be entirely verbal, and hence it may be preferable to designate postepisodic memory as categorical rather than semantic.

Learning that eventuates in categorical memory necessarily involves a number of stages, although these need not be temporally discrete. The stored information that forms the substrate for categorical memory must accrue from experiences in which relevant relationships among stimulus inputs or their aspects are perceived, for example, observation of use of a word in context or the relation between an exemplar and a category label. The accumulating information generally undergoes transformations as a consequence of cognitive operations such as grouping and chunking, normally occurring in the course of rehearsal, or reorganization resulting from the perception of relationships between items of information and retrieval cues that will be useful for aiding recall in test situations. Finally, accessibility of material for recall tends to decline during periods of disuse and can be maintained in an active state only as a consequence of reactivation during the interval between a learning experience and a test for recall.

Memory and Learning

All learning involves memory. However, learning is generally taken to have some cumulative aspect and some systematic relation to the individual's ongoing behavior and adjustment to the environment. Memories can (although they need not) comprise merely isolated fragments of information concerning past experience. But, whereas memory may be simply memory for an event, learning is generally taken to be learning about some subject matter. In education, especially, one is concerned with learning in the sense of the acquisition of information about the world that provides the basis for intelligent behavior: knowledge of spatial relations on small and large scales, knowledge about histories of events over short- or long-time scales, factual knowledge, concepts, values, and costs associated with actions and outcomes.

Among the many different ways in which memory enters into learning, it is important to distinguish between the role of memory in the learning process and its role in representing the products of learning. This distinction relates closely to the partition of both research and theory in terms of short-term versus long-term memory. The short-term systems are essential components of the mental apparatus that accomplishes the processing of perceived items of information into forms that can be retained over the longer intervals that are of principal interest in educational research.

The concept of working memory and the processes of selective attention that operate in it offer a unified interpretation of phenomena that have traditionally been assigned to quite distinct categories. It has been well known since Thorndike's (1931) research on belongingness that human learners ordinarily acquire information about relationships between events or items only if they perceive these relationships as significant at the time of a potential learning experience. Thus, for example, if an individual is engaged in learning the names associated with the faces of previously unacquainted individuals and is presented in sequence with face 1-name 1, face 2-name 2, and so on, the individual will tend to learn associations that enable later recall of name 1 in the presence of face 1, and name 2 in the presence of face 2. However, no association forms to mediate recall of face 2 in the presence of name 1, even though these were experienced in just as close temporal contiguity as either of the name-face pairs. As a consequence of a normal task orientation, the learner evidently attends to the relationship between a face and the name that goes with it but not between a name and another face that simply happens to be perceived at approximately the same time. Consequently, only the former relation becomes established in working memory.

A large literature on intentional versus incidental learning has come to be interpreted in much the same way (Postman, 1976). In conformity with everyday observation, many experimental studies have shown that individuals who are instructed or otherwise motivated to learn particular materials in experimental situations exhibit much better recall than individuals who are exposed to the same material without any intention to learn. It proves also that the learner's ability to recognize the material later is essentially unrelated to the intentional-incidental distinction (Estes & DaPolito, 1967). Passive exposure to the material leads to memory traces capable of producing an experience of familiarity when the material is reencountered. However, only active attention to aspects of the situation (retrieval cues) relevant to later recall produces facilitation of recall over the level characteristic of incidental learning. In terms of the flow of information through the cognitive system, it appears that all of the material perceived is registered in short-term memory, but only aspects or elements relevant to a current task situation, or to the individual's current motives, are selected for maintenance by rehearsal or rehearsal-like processes in active working memory. And only information that enters working memory becomes encoded and organized in a form to enable later recall or reconstruction.

The Problem of Encoding in Memory

One point of agreement among contemporary investigators is that memory is not simply a verbatim record, but rather an encoded representation of the individual's experience. What is a code? In general, it is a representation that stands for but does not fully depict an item or event. The representation of a scene in a photograph would not be said to be encoded because it preserves all of the information in the scene (up to the resolving power of the film). In contrast, the representation of the same scene in the human memory system is said to be encoded because much of the information in the visual input is systematically discarded during processing, and the representation preserves only the values of the stimulus on certain attributes or dimensions.

Sometimes a code is sufficient to enable later reproduction of a learning experience in considerable detail, but sometimes it is sufficient only to identify which of alternative categories the experience belongs to. For example, memory for a route through a town may include specific physical features of the terrain and buildings passed during the trip, or it may take the form of a sequence of instructions regarding directions to take at various choice points. Memory for a text passage may include specific statements or may constitute only a record of the kinds of facts or ideas communicated (Anderson, 1980).

In general, there tends to be a progressive lo...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- CONTRIBUTORS

- PREFACE

- 1 LEARNING THEORY

- 2 INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT

- 3 MOTIVATION

- 4 INTELLECTUAL ABILITIES AND APTITUDES

- 5 LEARNING SKILLS AND THE ACQUISITION OF KNOWLEDGE

- 6 PROBLEM SOLVING AND THE EDUCATIONAL PROCESS

- AUTHOR INDEX

- SUBJECT INDEX