eBook - ePub

Rich and Poor Countries

Consequence of International Economic Disorder

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This 4th edition has been revised to take account of the onset of world recession and the fall in commodity prices that have brought increasing poverty to some of the world's poorest countries.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

Perspectives

1 Introduction: The Current Economic Crisis and the Developing World

The current world economic crisis is a central concern of all students of economics today, and especially of those studying development problems. Theorists investigate the flaws in our approaches and institutions that gave birth to this present crisis. Policy-makers query the institutions and the rules that governed and shaped economic life in the post-Second World War era. The man in the street seeks an insight into the working of the national and the international economy in order to understand the implications of this chaos.

An alarming aspect of this concern is the introversion and shortsightedness of many of the solutions and schemes that are now put forward to overcome the impending catastrophe. The crisis is conceived of as being precipitated by events regarded as external to the western economic system—the instability and recent fall in primary commodities, the ups and downs of oil prices and the gyrations of OPEC politics, wars in the Middle East and elsewhere, droughts and famines in Africa exacerbated by civil wars, continuing debt crises, etc.—and ad hoc and piecemeal solutions are devised that seek to insulate the western world from such developments in the future. International economic organizations create elaborate mechanisms for coping with the balance of payments and debt problems arising, not only in the developing countries but also within the western world.

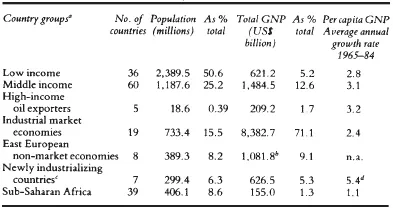

Table 1.1 describes the structure of the world economy in 1984. From this table we see that the global pattern of production and consumption is marked by a high degree of inequality. 50 per cent of the world’s population has a per capita gross national product (GNP) that is less than 3 per cent of the per capita GNP of the 15 per cent of the world’s population living in the industrialized western nations. Taking the world as a whole, the developing countries, which have approximately 75 per cent of the world’s population, have a GNP of less than 20 per cent of the world’s total. The vision of economic inequality conjured up by these figures is staggering (this point is developed in greater detail in Chapter 2). As the average annual growth rate of GNP per capita since the mid-1960s has been virtually the same for both the developed and the developing countries, as a whole, there is clear evidence that the actual distance between the rich and the poor countries has further widened during a period when the world community had implicitly undertaken the responsibility of bridging the economic gap between the nations.

The difference in the material condition of people living in various parts of the world is reflected most graphically in two socioeconomic indicators: the literacy rates and infant mortality rates (see Table S.1 in the Statistical Appendix, p. 304). Together these two indices provide a telling measure of the development of human resources and standard of living of a country, and they are more significant than indicators based on GDP. (Developed countries exhibit varying rates of production of heavy manufactured goods, but they all have high literacy and infant mortality rates.) Literacy in developing countries is considerably lower than in the rich nations, and the infant mortality rate is about seven times higher in the former. This structural characteristic of the economy reflects the inability of the poorer countries to exploit their economic potential. Whereas the rich countries are capable of using their economic resources in a way that maximizes productivity in the long run, the developing countries are forced to tolerate the existence of disguised unemployment of labour and underutilization of capital. They are faced with the challenge of devising or adapting a technology that can lead them to the realization of their economic potential. Their basic motivation as participants in the international economy is reflected in their desire to obtain support for development policies that aim at bridging the technological gap—as measured by the differences in literacy and infant mortality rates—between the ‘have’ and ‘have not’ nations of the world.

Table 1.1 World economic structure, 1984

Notes

a For countries in each group refer to World Development Report 1986.

b Net Material Product. Derived by applying the 1983/4 growth rates to NMP 1982 for Eastern Europe.

c NICs: Yugoslavia, Mexico, Brazil, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong (OECD Economic Outlook 1986, Paris).

d Data for Taiwan from Economic Intelligence Unit, Annual Report 1985 (London).

Source: World Bank, World Development Report 1986 (Washington DC).

To be sure, the developing world is not without cleavages. As Table 1.1 illustrates, there are significant differences in the economic structure of the various segments of the Third World. At one extreme are the thirty-nine countries of sub-Saharan Africa with incomes per capita under the $400 benchmark and imperceptible or negative growth rates. At the other extreme are the oil-exporting countries, which continue to reflect the impact of the 1970s oil price rises with per capita incomes of over $11,000. An emerging group of developing countries exhibiting high growth rates are the newly industrializing countries (NICs). Their per capita income is approximately $2,000, while their average annual rate of growth since the mid-1960s is more than double that of the rich countries.

Despite this structural difference, and despite the consequent differences in the requirements and needs of the various countries, the Third World has maintained a broadly united posture in international economic negotiations. This unity reflects the essentially unchanged nature of the relationship between the rich and the poor countries, despite the events of the past decade. The dramatic increase in oil prices in 1973/4 and the similar rise in the price of some primary commodities led a number of analysts to believe that the resource-rich developing countries had succeeded in achieving a breakthrough that would permanently and irrevocably alter their position within international commodity, factor and money markets. This belief was reflected in the call for the implementation of a New International Economic Order, in a resolution adopted by a special session of the UN General Assembly in 1974. However, though the oil crisis as well as other shortages emphasized the importance of a group of the poor countries in the international economy, it failed to bring about a restructuring of the world economy. Instead, the move towards alternative sources of energy, the evolution of the food crisis, the failure of the international community to bring about commodity price stabilization, the growth of protectionism and the newly emerging debt crisis depict a protracted conflict between the rich and the poor countries. Moreover, the unity of the Third World (as also that of developed countries) is itself threatened by these events, for despite the public statements and resolutions in the United Nations the fact is that the position of the oil-exporting developing countries and the NICs is today vastly different from the rest of the Third World, particularly from the countries of sub-Saharan Africa. Hence there exists the potential for conflict of interest within the hitherto ostensibly united Third World. The oil crisis in particular provided an apt illustration of the difference in approach and in objectives pursued by a group of formerly poor countries that suddenly found themselves in the unique (if temporary) position of having the rest of the world at their mercy.

The New International Economic Order

The term ‘New International Economic Order’, often referred to as NIEO, suggests two immediate thoughts: the first is related to ‘new’ and the second emphasizes ‘order’.

The new versus the old

If there is to be a new order, then presumably it must be contrasted with an old order, an OIEO, namely the Bretton Woods system, which was established at the end of the Second World War as a result of Anglo-American negotiations, with an absorbing interplay between the intellect of Keynes, subtly representing British interests, coming up against the hard facts of US power and economic supremacy.

The Bretton Woods system certainly served the western industrial countries extremely well during the twenty-five years 1946–71, an era of unprecedented progress and full employment without inflation. Here, in what may be called the ‘First World’, severe poverty almost disappeared. The tremendous increase in GNP and technological power was accompanied by more equal internal income distribution, symbolized by the term ‘welfare state’. Furthermore, the growth of the various countries concerned was convergent - that is to say, those that were the richest at the beginning of the period, including the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Switzerland, showed relatively slow growth, whereas the poorest, and specifically those defeated and devastated during the war, such as West Germany and Japan, showed the most rapid growth. It is a debatable point to what extent the big success story of these twenty-five years was due to the Bretton Woods system as such, or perhaps to an extremely farsighted and generous US policy embodied in the Marshall Plan. Probably it was a combination of the two that produced the end result.

Even for the Third World the Bretton Woods era was, in some ways, not a bad period, since many countries—and South Korea is an outstanding example—then laid the foundations of their economic growth. The GNP of the Third World as a whole increased by 5–6 per cent per annum, a growth rate very similar to that of the industrial countries—although, of course, a much higher percentage of this aggregate growth was swallowed up by population growth, so that growth per capita was less. The ‘trickle-down’ effect of growth from the industrial countries to the Third World was unmistakable and the flow of aid was considerable, particularly during the earlier part of this period, even if at no time comparable to the Marshall Plan. A number of developing countries clearly achieved the situation described by Walt W. Rostow in his famous image—so typical of the technological aura of the 1950s and early 1960s—of the ‘take-off into self-sustained growth’.

However, there were great sources of weakness in the progress made by many Third World countries during the Bretton Woods era. Above all—in sharp contrast to the industrial countries—their growth was divergent, that is to say, the better-off tended to grow faster, leaving the poorer countries far behind. Thus the Third World began to split during this period. A group of what are now called the newly industrializing countries (typified by Brazil and Mexico in one hemisphere and by Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong in another) left behind a group of poorest countries, a ‘Fourth World’ (typified by India, Bangladesh, Indonesia and most of Africa).

The growth was also divergent in the internal sense, because contrary to what happened elsewhere it was accompanied by increased inequalities in income distribution. Thus, because of divergence both between and within countries, Third World poverty did not show any signs of disappearing or even diminishing. Further intensified by the speeding-up of population growth due to the reduction in death rates—in itself a sign of the progress achieved—the absolute volume of world poverty was thus increasing quite rapidly during the Bretton Woods era.

Another source of weakness for the Third World countries was the tendency for their terms of trade to deteriorate in the course of the Bretton Woods era. This had in fact been forecast initially, although it remained a contested view; but certainly, with the exception of the temporary boom during the 1950/1 Korean War, the prices of primary commodities showed a distinct tendency to sag in relation to those of manufactured goods, to the great disadvantage of the Third World.

Fundamentally and perhaps even more important, was the rapid development of technology in the direction of greater sophistication and capital requirements, making the technological gap progressively more unbridgeable (see Chapter 2).

There were thus plenty of reasons for Third World countries to be dissatisfied with the Bretton Woods order. As regards the deteriorating terms of trade, it is of special interest to note that, in the original Keynesian conception, the system was to rest on three pillars: a world central bank (realized in the attenuated form of the International Monetary Fund, IMF), a world development agency (realized in the attenuated form of the World Bank) and an international trade organization. The charter of the latter was negotiated in Havana during 1947 but was never implemented owing to the failure of the US Congress to ratify the proposals. The gap left was partly filled by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) with much more limited provisions. It was, therefore, a case of retributive justice that the complaints of the Third World about the inefficiency of the Bretton Woods system should have been so strongly concentrated on the problems of commodity trade (see Chapter 5). This dissatisfaction encouraged the formation of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). But its effective working in the interests of the poor countries has been affected by its lack of support from the developed world.

Order versus disorder

There is another way of reading the demands for a New International Economic Order, with the accent on the last word. The Bretton Woods system has been dated above as ruling for twenty-five years, from 1946 to 1971. Since then, however, it has visibly disintegrated, and only remnants now remain.

This collapse is often associated with the oil embargo by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the quadrupling of oil prices in late 1973. However, while that action may well be considered as the last nail in its coffin, one of the chief elements of Bretton Woods—the free convertibility of the US dollar as the world’s main reserve currency into gold at a fixed low price—was suspended as early as 1971. That was already a clear signal that the system was no longer working. This was followed in 1972 by the world food crisis resulting from simultaneous crop failures in the Soviet Union, India and Sahelian Africa, and poor or moderate production elsewhere. This meant that the large surplus stocks of food, which had been an essential part of the Bretton Woods system, dwindled away rapidly, and the prices of cereals quadrupled like those of oil. Recovery from the shock to the world economy in the mid-1970s was slow, highlighting the growing obsolescence of the old order.

So the demand for an NIEO must be contrasted not with an OIEO, but with the subsequent state of disorder. A slowing-down of growth and rising unemployment combined with speeded-up inflation expressed itself in a major recession in the industrialized countries. ‘Stagflation’ was an entirely new experience because the foundation of the Bretton Woods system was a trade-off between unemployment and inflation. The recession had the effect of slowing down growth rates world-wide, the hardest hit being the oilimporting poor countries. The early impact of the recession was contained by the commercial banks, which recycled oil revenue in the form of loans to many developing countries. The unforeseen consequence of this action was to be felt at a later stage. But at the time, these developments created a fresh situation, namely a mutual interest in the re-establishment of economic order. Whether this was defined as something really ‘new’ or a return to the kind of economic order that existed previously was perhaps more a matter of semantics and political preference than of reality.

It was initially felt that the cost to the industrial countries as a result of stagflation (that is, the difference between what would have been produced each year if the steady growth of the Bretton Woods era had continued compared with what in fact was produced) would be an impetus to them to agree to the concessions that were demanded as part of the NIEO. The expectation was that measures taken to aid the economic recovery of the developing countries would, in the long term, be beneficial to the world economic order by acting as the ‘engine of growth’ for the world as a whole. The NIEO negotiations thus evolved around the financing of the Common Fund, the reduction of trade barriers, stabilization of commodity prices, tighter control of the activities of multinational corporations, improved representation for the poor countries in international agencies like the IMF, IBRD (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development) and the GATT, the strengthening of UNCTAD and the adoption of a 0.7 per cent target for official development assistance.

Unfortunately, the early stages of the negotiations proved that the clear existence of a major mutual interest was not sufficient to guarantee the successful adoption of the NIEO proposals. This was partially owing to a lack of consensus on the main symptoms of what was actually wrong and to the fact that the Third World countries gave prominence to the need to eliminate or reduce perceived inequalities and inequities in the system. In addition, the slow recovery of the economics of the industrialized countries, the negative effects of the prolonged recession on world trade comb...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Abbreviations

- A Note on Terminology

- Dedication

- Preface

- Part I: Perspectives

- Part II: Trade

- Part III: International Finance

- Part IV: An Overview

- Statistical Appendix

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Rich and Poor Countries by Javed Ansari,Hans Singer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.