eBook - ePub

A Jewish Archive from Old Cairo

The History of Cambridge University's Genizah Collection

- 277 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Explains how Cairo came to have its important Genizah archive, how Cambridge developed its interests in Hebraica, and how a number of colourful figures brought about the connection between the two centres. Also shows the importance of the Genizah material for Jewish cultural history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Jewish Archive from Old Cairo by Stefan Reif in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

A WONDROUS JEWISH SITE

Over seven hundred years ago, when a few brave souls in England were bearing the torch of learning to damp and distant Cambridge, and almost four centuries before Hebrew was taught at its famous university, a Jewish community known throughout the Islamic empire for its social and political stability, as well as its economic and cultural achievements, had already been flourishing on the Nile for two hundred and fifty years. The community was that of old Cairo and, almost without realizing it, the officials of this significant Jewish settlement were beginning to build up an archive that was destined to achieve scholarly immortality as the Cairo Genizah.

ORIGINS OF OLD CAIRO

Egyptian Jewish centres, such as that of Alexandria, had blossomed during the Hellenistic and early Roman periods and, with their special combination of Greek and Hebrew culture, had made a notable contribution to the development of both Jewish and Christian life and letters. They undoubtedly began to decline in the unhappy conditions that prevailed for them in the early Christian centuries and were given little opportunity of reversing this process under Byzantine rule. It thus seems reasonable to suppose that whatever Jewish population still survived to witness the Islamic conquest of 639–641 c.e. would have greeted the conquerors with at least a modicum of enthusiasm, hopeful of some alleviation of their burdens. Jews from other areas were optimistic about their prospects under the new Muslim régime and a number of them appear to have brought up the train of the invading forces and settled in the newly occupied territory. Among the communities that they established was one at Fustat, the first city to be founded by the Muslims in Egypt, and the initial place of residence of the Arab governors.

Positioned on the east bank of the Nile at the head of the delta, dominating access to Lower Egypt, the site chosen by the conquerors had long been acknowledged as one of strategic importance. In pre-Christian times, an important settlement existed there, by the famous river, and was entitled “Babylon”, either after a group of Babylonians who once occupied it, or after an Egyptian name corrupted in transmission. A Roman fortress with high walls and impressive towers was built there in the third or fourth century (its remains are still visible) and it was there that the Byzantine Christians surrendered to the invading Arabs on Easter Monday, 641 c.e.

The new Islamic empire followed the lead given by its predecessors and the capital city established at what it called Fustat-Misr in 643 c.e. grew to become the unrivalled centre of Egyptian economic and political life, a position it held for some three hundred years. It did then begin to cede some of its power but had the satisfaction of seeing its role and status inherited by a former suburb some two miles to the north-east, called Cairo (al-Qahira) by the Fatimid dynasty that expanded it as the new administrative capital. The process of Fustat's decline was a gradual one that was not completed until the fifteenth century and in the intervening period the older city remained an important religious and commercial centre. During its earlier heyday, it was one of the wealthiest towns in the Islamic world, with some of its tallest known buildings, a bustling metropolis with affluent minority groups of Christians and Jews.

Paradoxically, detailed information about the Jewish population of Fustat is available only from the beginning of the Fatimid period in 969 c.e., that is, precisely from the time at which the older city's fortunes began to wane. Some scanty references do, however, permit the reconstruction of its earlier history. The community was the most important Jewish settlement in Egypt and took advantage of the communications system of the vast Islamic empire to maintain contact with its co-religionists in North Africa, Babylon and the Holy Land. That the scholarly achievements of the Egyptian Jewish community in general were not insignificant is clear from the fact that it produced one of the most distinguished Jewish sages of all time, Sa‘adya Gaon ben Joseph. That scholar, who became head of the leading rabbinical centre in Sura in southern Babylonia, originated from Fayyum, some fifty-five miles to the south-west of Cairo, and there is no reason to assume that the products of that particular community were unique in the Egypt of that period.

Be that as it may, it was Fustat's prosperity rather than its scholarship (which was certainly more distinguished elsewhere) that attracted Jewish

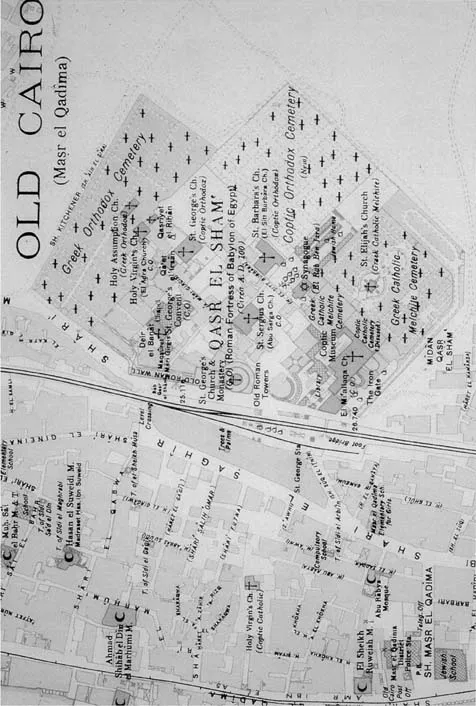

1 — Map of Cairo, showing the Ben Ezra synagogue in the medieval part of the city (Survey of Egypt, 1927)

immigrants from Babylon and Eretz Yisrael and they duly established synagogues in which they could adhere to their own liturgical rites and customs. In addition to these Iraqi and Palestinian congregations that were, as Rabbanites, faithful to the tenets and practice of talmudic Judaism, there was also a large community of Karaites, committed to its own more Bible-based interpretation of the Jewish traditions, and supporting its own synagogue. According to Muslim testimony, one of these places of worship was acquired in 882 c.e. in a rather unusual manner. Faced with a demand by the ruler of Egypt, Ahmad ibn Tulun, for a substantial, financial contribution to the cost of his war effort, the Coptic Patriarch was forced to sell some ecclesiastical property. One of the transactions involved the purchase of St Michael's church by the Jews for conversion into a synagogue. Even if we are persuaded to accept the veracity of this report, it is by no means clear that the synagogue in question is the one in which the Genizah collection was amassed, as claimed by some researchers. The most recent historical and archaeological studies have raised serious doubts about such an identification.

FUSTAT AT ITS ZENITH

It is no coincidence that the Fatimid period (969–1171), which saw Fustat reach the zenith of its commercial power, should also prove the richest in source material for Jewish history. The Jewish community was strengthened by the influx of substantial numbers of immigrants from the Holy Land and from North Africa (especially Tunisia) and numbered a few hundred families. Its members took advantage of the unprecedented degrees of administrative efficiency, economic expansion and religious tolerance that were generally prevalent under the Fatimid dynasty and built the kind of society in which they could expand and consolidate their religious and communal institutions. The distinguished title of Nagid was granted to the head of the Egyptian Jewish communities and the appointment, carrying as it did the responsibility of representing the Jews to the authorities, was usually held by one with an influential position at court. During the first century of Fatimid rule, Egyptian Jews looked to the Palestinian religious authorities (ge'onim) for guidance but by the twelfth century the situation was reversed and the centre of religious power for the whole Egyptian, Palestinian and Syrian region was to be found in the Fustat/Cairo area. With these and similar developments, the written word, both documentary and literary, naturally acquired a position of growing importance. Through a fortuitous combination of circumstances, a considerable proportion of the vast amount of textual material emanating from the Jewish community, or passing through its hands, was preserved, thus making possible a fascinating reconstruction of medieval Jewish life.

The success story of the Fatimid caliphs in Egypt was also itself somewhat fortuitous. It had more to do with the general political situation in the Mediterranean world of their day than with any inspired leadership or novel policies on their part. The collapse of the former centre of Mediterranean trade in Tunisia and the gradual replacement of Byzantium by the Italian republics as the controllers of commerce on the northern shores of the Mediterranean gave Egypt the opportunity of dominating eastern Mediterranean trade. Its merchants forged strong commercial links with India and East Asia and produced what was effectively a contemporary economic miracle. On the military side, Fatimid Egypt did not dominate the area but neither was there any other power strong enough to overthrow her. Something of a balance was maintained between the emergent Seljuk Turks, the inconsistent Crusader forces, and the Fatimids themselves, and this amounted to a satisfactory situation for the Egyptian centre. On the domestic front, Fatimid achievements had their roots not so much in how the rulers directed their subjects but rather in the degree to which they permitted them to exercise their own initiatives. The energy, administrative ability and economic enterprise of Tunisians, Christians and Jews were given their head and major advantage thereby accrued to the state. At the same time, by their relatively liberal approach to the people and their skilful use of propaganda, the administration ensured that it remained internally tolerable and that no pretexts were given for outbursts of popular dissatisfaction.

No matter how tolerant the atmosphere, the Jews could, however, never be more than second-class citizens in the Islamic environment, and were always liable to active persecution when religious fanaticism took hold of those with the power to indulge in its cruder manifestations. Even during the halcyon days of the Fatimid hegemony, storms could sometimes break out and there is evidence to suggest that members of the Shi‘ite Isma‘ili sect, to which the Fatimid rulers belonged, were among those with a tendency to disturb the calm. The worst instances of religious intolerance occurred in the latter part of the reign of the caliph, al-Hakim (996–1021). Not psychologically the soundest of the Fatimid dynasty, he ordered the Christians and the Jews to wear marks of identification and denied them the right to ride horses or purchase slaves. He followed this up in about 1012 by ordering their forcible conversion and the destruction of their churches and synagogues. What was a rather extraordinary event under the Fatimids became a more run-of-the-mill occurrence under later dynasties when the whole situation deteriorated for both the city of Fustat and its Jewish community.

THE CITY'S DECLINE

The earliest manifestations of this decline may already be detected during the Fatimid period itself. As early as the middle of the eleventh century, during the latter and somewhat blighted part of al-Mustansir's reign, Fustat suffered years of severe famine, aggravated by the outbreak of epidemics. The city seems to have recovered from this setback, just as it did more than half a century later when the problem was the collapse of buildings that had not been maintained in a satisfactory state of repair. Although efforts to rebuild and to reconstruct were sufficiently successful to ensure that recovery and further development remained possible in most of the Fatimid period, the situation changed as the dynasty moved into its final years. In a measure designed to foil the advance of the Crusader army, which was approaching its environs in 1168, the city was evacuated and burnt down. Though later rebuilt, it was hardly in a position to withstand the additional catastrophes of famine and plague visited upon it a few decades later. Indeed, it was during the Ayyubid dynasty (1171–1250), founded by Saladin, famous scourge of the Crusaders, who had seized power at the convenient deaths of both his overlord Nur-al-Din and the deposed Fatimid caliph, that fatal blows were struck at Fustat's centrality. As Egyptian sea power waned and its rulers became more introspective, the once great commercial centre of Fustat finally had to acknowledge the preeminence of Cairo, its sometime suburb. While the grandson of Moses Maimonides still followed the example of his father and grandfather and resided in Fustat, subsequent generations of the family, still occupying the position of Nagid, moved north, to join the majority of the population in Cairo. By the end of the fourteenth century, there were four synagogues in the newer settlement as against three Jewish places of worship in the older centre.

The Mamluk period (13th–16th centuries) may justifiably be designated as one of the darkest ages in Egyptian Jewish history. The administration was reorganized and placed in the exclusive hands of Muslims who adhered strictly to Islamic law. The large-scale persecution of religious minorities was the order of the day and, not content with imposing discriminatory legislation on the Jews, the Muslim rulers resorted to grave physical violence, at one stage even insisting on the total closure of synagogues. Under such conditions, it is hardly surprising that the Jewish community suffered economic decline and a reduction in population. On the cultural side, the relative paucity of local Jewish sources dating from the Mamluk period is a further reflection of the wretched plight in which the community then found itself. Things finally took a turn for the better in the early sixteenth century, when power passed into the hands of the Ottoman Turks, and the arrival of sizeable numbers of refugees, as a result of the Spanish Expulsion, breathed fresh life into the ailing Jewish body. The structure of the community had already undergone considerable change in earlier centuries with the gradual integration of both the Palestinian and Babylonian immigrants into the dominant Tunisian element, and their ultimate disappearance as independent entities. The Spanish influx took this process a stage further and effected a tripartite division of the Rabbanite community into Musta‘rabīn, the native Arabic-speaking faction; Maghribyīn, that is, those who had their origin further west in North Africa; and Sefaradim, the refugees from the persecutions in Spain and Portugal.

SEFARADIM AND OTTOMANS

In the subsequent jockeying for power and influence within the community at large, it was the last-mentioned, the newest arrivals, who, by dint of their cultural heritage, self-confidence and clear-cut identity, emerged victorious. The religious and lay leadership became predominantly Sefaradi and communal customs were gradually altered to accommodate them to the rites familiar to the Spanish emigrés. The newly reconstituted community took full advantage of the economic opportunities afforded by the Ottomans during the early part of their rule and shouldered heavy responsibilities relating to the financial administration of the country. It also came to enjoy considerable improvements in its status and conditions, as well as in its standards of Jewish learning. The halt called by the Ottomans to the intellectual, political and economic decline of Egypt proved, however, to be no more than temporary. Financial extortion, court intrigue, political corruption and arbitrary execution came to typify the régime and the position of the Jews once again bordered on the intolerable. The office of Nagid was abolished by the government in the second half of the sixteenth century and Jewish officials in the state treasury took over the function of representing their fellows to the authorities, often at the ultimate personal cost. A large proportion of the Jewish community suffered

2 — Synagogue officials depositing worn-out texts in the Genizah

(diorama at the Nahum Goldmann Museum of the Jewish Diaspora, Tel Aviv)

(diorama at the Nahum Goldmann Museum of the Jewish Diaspora, Tel Aviv)

extremes of poverty and ignorance. Jewish learning stagnated and Jews were not spared the crudest physical attack...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- CULTURE AND CIVILISATION IN THE MIDDLE EAST

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 A WONDROUS JEWISH SITE

- 2 THE CAMBRIDGE CONNECTION

- 3 DETAILS OF THE CAST

- 4 TEXTS IN TRANSIT

- 5 WHOLLY FOR BIBLE

- 6 IN RABBINIC GARB

- 7 POLITICS, PLACES AND PERSONALITIES

- 8 EVERYDAY LIFE

- 9 BOOKISH AND LETTERED

- 10 A CENTURY REACHED

- INDEXES