![]()

Introduction

Good Leaders Learn consists of a series of probing interviews with 31 leaders, representing a wide cross section of society—from business, government, health care, sports, and the arts to science and the military. The leaders vary in their ages and levels of experience. And they come from different places in the world, including Canada, the United States, India, Turkey, Bangladesh, Ireland, Germany, Hungary, and Hong Kong.

To give them time to reflect on their answers, each leader received the set of questions in advance of the interviews. Although each of these 45–120-minute interviews was somewhat structured, I told each leader that I hoped we would have a frank and candid conversation about their life and leadership career, the events that affected them, and the people who influenced them. And they did not disappoint me. These leaders shared their challenges, heartaches, and triumphs, providing deep insights into how they learned to lead over the course of their careers.

I became interested in writing a book on how leaders learn to lead for two, interrelated reasons: the discussions and controversies about leadership that arose with the recent financial crisis, and the thoughts and stories about leadership that different leaders have shared with students in my classes at the Ivey Business School.

The Financial Crisis

The global financial and economic crisis that began in late 2007 and continues to influence markets today vividly underscored that the world needs better leadership. In 2008, my colleagues Jeffrey Gandz, Mary Crossan, Carol Stephenson, and I undertook a close examination of this crisis and the impact of leadership—or the lack of good leadership—on this crisis. We engaged more than 300 senior business, public sector, and not- for-profit leaders from across Canada, as well as from New York, London, and Hong Kong, in open discussions on the role that organizational leadership played before, during, and after the crisis.

In a very real sense, we put leadership on trial, not to identify or assign blame, but to learn what happened to leadership during this critical period in recent history. We wanted to use what we learned to improve the practice of leadership today and to inform the development of the next generation of leaders for tomorrow. And as we analyzed the role of leadership in this crisis, we were faced with one major question: “Would better leadership have made a difference?” Our answer was an unequivocal, “Yes!”

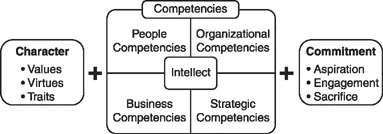

We presented our conclusions in the form of a public statement of principle—a manifesto that addresses what good leaders do and the kind of people they need to be (Gandz, Crossan, Seijts, & Stephenson, 2010). A preview of our report is available online: http://www.ivey.uwo.ca/research/leadership/research/LOTreportpreview.htm. Our research illustrates that good leadership is based on the competencies, character, and commitment of leaders. Figure 1.1 shows how these three pillars are reflected in the decisions that good leaders consistently make and in the plans and actions they routinely put into play.

Competencies include the knowledge, understanding, skills, and judgment leaders are expected to have, if not early in their careers, at least in their mature phases. There are at least four competencies: strategic, business, organizational, and people. These are typically acquired through formal education, training, and development programs, as well as coaching and mentoring in the workplace (Crossan, Gandz, & Seijts, 2008). Competencies determine what leaders are able to do.

Underpinning these competencies is general intellect. Being smart matters! It matters because general intellect gives leaders the tools to understand the complex cause-and-effect relationships among the drivers of organizational performance. These drivers include commodity prices, currency fluctuations, competitive actions, tax policies, changing consumer demands, and the other cultural, demographic, and environmental trends that shape the way we live and work.

Character, which can be expressed as a set of virtues, values, and traits, is also fundamental to good leadership. It shapes how we engage with the world around us, what we notice, what we reinforce, who we consult, what we value, what we choose to act on, how we react, and how we make decisions about the challenges we face. Character is developed both early in childhood and in the later stages of life through our experiences and our reflection on these experiences. Character influences what leaders will do in different situations.

Figure 1.1 Leadership competencies, character, and commitment.

Commitment is equally critical to good leadership and it's about more than simply assuming a leadership role. True leadership commitment is about being willing to do the challenging, often grueling work of leadership and to continue to develop as a leader. When that caliber of commitment fades, leaders become mere figureheads. Commitment is forged from an individual's aspirations, from their desire to be fully engaged in their work and their willingness to make personal sacrifices in return for the opportunities and rewards that come with the role of leadership.

All leaders, at some point, will change in terms of their leadership aspirations, how much they want to be involved in their organization's work, and how much they want to sacrifice to remain a leader. When leaders no longer want to lead, they must step aside for the sake of both their performance and the development of new leaders in their organization.

The concept of the “born leader” may be attractive and suggests that good leadership is just a function of natural selection. But, for most people, leadership is learned. It is truly a lifelong process.

Leaders Visiting the Classroom

In addition to my research with others on leadership development, I teach courses in organizational behavior and leadership, wherein I often welcome outstanding leaders into my classroom to talk about leadership. They all told me that they learned to become a leader—and that their development to become an even better leader is an ongoing process. This made me think. How do leaders go through the learning process? What are the formative experiences that influence leaders? How do they reflect on events and truly learn from their mistakes and successes? How do they come to trust others and their own intuition? How do they unlearn dysfunctional habits? How do they become more self-aware?

For example, how did the president and chief executive officer (CEO) of Maple Leaf Foods, Michael McCain, learn to place his leadership on the line during the listeriosis crisis (see Chapter 18)? How did he learn the importance of accountability and taking ownership? He had to make multimillion dollar decisions within minutes; how did he develop the wisdom to act under high- pressure and openly public situations?

Why did the then president and chairman of ING DIRECT USA, Arkadi Kuhlmann, ask all of his employees each year to vote on whether they thought that he should remain in his post (see Chapter 14)? How did he develop the humility—and gain the trust of employees—to confidently ask that question again and again, knowing that some years are better than others?

How do leaders such as Sukhinder Singh Cassidy learn the politics of organizational life early on in their careers, enabling them to quickly assume more and greater leadership responsibilities (see Chapter 32)?

Craig Kielburger was inspired by reading a headline in the Toronto Star about child labor when he was 12 years old. How did he act on that inspiration to become a charismatic activist for the rights of children? How did he learn to deal with the cynicism that persists about his youth and perceived naivety?

How do leaders such as Lieutenant General (Ret.) Roméo Dallaire and General (Ret.) Rick Hillier learn to be decisive in life- and-death situations? How do they cope with the fact that all eyes are on them in these critical times? How do they learn to carry the burden of leadership?

How do leaders such as the Canadian Football League's Michael “Pinball” Clemons develop the patience to wait for the right time to make a change in the team or voice an opinion? How did he learn to pick his moments?

Good leaders learn from their own experience and from the experiences of other leaders they have seen in action, good or bad. They learn from their peers, the people who report to them, their competitors, partners, and suppliers. They learn from their critics and their allies. But, to learn in the first place, they must be motivated and have the capacity to learn.

Not every leader is good at learning or is prepared to constantly learn. Some leaders are not open to new ideas. I have seen that in the classroom, too. Others lack the courage to move outside of their comfort zones. There are also overconfident and arrogant leaders who lack the humility essential for learning. Still others are narcissistic, surrounding themselves with “yes” people, who would never suggest that the leader learn something new. Some leaders may simply lack the intellect to learn. Others become lazy about learning, believing that they have reached the peak of their careers and have no more to learn. The fact that these leaders can't learn or don't want to learn undermines their leadership performance. Inevitably, they fail. We have seen too many examples of these types of bad leadership in the recent past.

By contrast, good leaders never stop learning. Even at the higher levels of an organization, they find themselves learning how to lead in new and often ambiguous situations.

Developing Better Leaders

The world craves better leadership. That's apparent from today's headlines alluding to leadership failures in business, government, science and education, sports, the military, and other sectors. For example, the 2012 Edelman Trust Barometer shows an unprecedented gap in the public's trust in both government and business institutions (StrategyOne, 2012). A recent Nanos Research poll reveals that about a third of Canadians distrust scientific findings in the areas of energy technologies, medicine, climate change, and genetically modified crops (Nanos Research & IRPP, 2012).

In 2012, several national and international scandals in sports, science, and the military further fueled this public skepticism about people in positions of power. There's the story of Lance Armstrong and the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency report that stripped him of his seven Tour de France titles and banned him from the sport for the rest of his life. Consider the Pakistani cricketers Mohammad Amir, Salman Butt, and Mohammad Asif and their conviction for spot- fixing matches. Think about Dutch researcher Diederik Stapel who admitted to fabricating data for his studies. And what about the Pentagon's 2012 survey results reporting that the number of sexual assaults at three military academies in the USA had increased by 23 percent compared to the previous year? One of these academies was the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, an internationally recognized institution for academic, military, and physical excellence, with an emphasis on leadership character.

Whether the quality of leadership in organizations improves or not depends on the efforts of many stakeholders—families, religious institutions, schools, boards, professional associations, educators, and senior leaders in all segments of societies. The Ivey Business School is a school of leadership. We aspire to be in the forefront of developing leadership courses and materials for both university-based and corporate leadership development programs. We conduct leading-edge research focused on real-world leadership challenges through the Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership. And our aim is to make this research relevant, accessible, and useful to leaders.

This book delivers on our commitment to leadership and leadership development. Through the interviews with leaders and our most recent leadership research, readers will benefit not only from a new and robust theoretical framework for leadership, but from finding out firsthand and up close how good leaders become better leaders through learning.

References

Crossan, M. M., Gandz, J., & Seijts, G. (2008). The cross-enterprise leader. I vey Business Journal [online], July—August 2008. Retrieved from http://www.iveybusinessjournal.com/topics/leadership/the- crossenterprise-leader

Gandz, J., Crossan, M., Seijts, G., & Stephenson, C. (2010). Leadership on trial: A manifesto for leadership development. London, Ontario, Canada: Ivey Business School.

Nanos Research & Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP) (2012). Green light for science. Caution on scientists [survey], December 28, 2012. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Nanos Research Canada Research Inc.

StrategyOne (2012). Edelman Trust Barometer 2012: Annual global study. New York, NY: Edelman.

![]()

Leadership Character1

In our conversations with business leaders during the Leadership on Trial project (Gandz, Crossan, Seijts, & Stephenson, 2010), they brought up the importance of character and values time and time again. Here is a selection of their observations about what happened during the financial crisis and why:

• “Some people were in denial. Others recognized there were big flaws—but some were unwilling to act or did not have the courage to act, and others thought they were too small to act.”

• “It appears to me that, you know, without sort of condemning society as a whole, we seem to lack a moral compass to sort of make the right decision when the reward system is suggesting that we should trade the future for the present. I think as a leadership grou...