- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Copper Plate Photogravure describes in comprehensive detail the technique of traditional copper plate photogravure as would be practiced by visual artists using normally available facilities and materials. Attention is paid to step-by-step guidance through the many stages of the process. A detailed manual of technique, Copper Plate Photogravure also offers the history of the medium and reference to past alternative methods of practice.

Copper Plate Photogravure: Demystifying the Process is part of the current revitalization of one of the most satisfyingly beautiful image-making processes. The range of ink color and paper quality possibilities is endless. The potential for handwork and alteration of the copper plate provides yet another realm of expressive variation. The subject matter and the treatment are as variable and broad as photography itself. This book's purpose is to demystify and clarify what is a complex but altogether "do-able" photomechanical process using currently available materials. With Copper Plate Photogravure, you will learn how to:

· produce a full-scale film positive from a photographic negative

· sensitize the gravure tissue to prepare it for exposure to the positive

· prepare the plate and develop the gelatin resist prior to etching

· prepare the various strengths of etching solutions and etch the plate to achieve a full tonal scale

· rework the plate using printmaking tools to correct flaws or to adjust the image for aesthetic reasons

· use the appropriate printing inks, ink additives, quality papers, and printshop equipment to produce a high

quality print

A historical survey and appendices of detailed technical information, charts, and tables are included, as well as a list of suppliers and sources for the materials required, some of which are highly specialized. A comprehensive glossary

introduces the non-photographer or non-printmaker to many of the terms particular to those fields and associated with this process.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Copper Plate Photogravure by David Morrish,Marlene MacCallum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Medios digitales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | A Brief History |

ORIGINS

The medium of photography is evolving toward ever more immediate and ethereal images that often barely exist as digital data. The ease of reproducibility has increased and the scope of dissemination has become instantly global. It was not long ago, however, when photography was mainly a chemical process—an image formed on paper or, more recently, a plastic support. When photography was invented in the 1820s, the image-making process was even more physical. A unique image was etched onto a metal plate through an acid resistant layer. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (French: 1765–1833) is credited with the first permanent photographic images using sensitized bitumen of Judea on a pewter plate—images that could ultimately be etched and reproduced as intaglio plates. He saw the potential of this process for quick, accurate reproduction of existing engravings (Figure 1-1). Niépce called these first successful photomechanical reproductions heliogravures. These prints, however, did not reproduce any of the smooth continuous tones we now associate with a photograph.

A partner of Niépce, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (French: 1787–1851), developed his own version of the photographic process after Niépce’s death. After the announcement of Daguerre’s invention of the daguerreotype in 1839, the process was immediately tested in order to make the one-of-a-kind daguerreotype plate printable as photomechanical intaglio plates. Hippolyte Fizeau (French: 1819–1896) devised a method using aquatint, etching, and even electroplating to create a printable daguerreotype plate. Dr. Alfred Donné (French: 1801–1878) published details of his process in June of 1840 after patenting his method of etching daguerreotype plates. He displayed his pale prints from etched daguerreotypes to the French Academy of Science in the same year. His process utilized the natural grain and acid-resisting properties of the mercury amalgam that forms the highlights and light tones of the image to etch the silver plating from the open shadow areas on the surface of the plate. Dr. Joseph Berres of Vienna made darker and richer images from daguerreotypes. He attained a deeper etch by using solid silver plates and building up the highlights with varnish.

Figure 1-1 Niépce used a waxed line-engraving as a positive and exposed it onto a pewter plate so it could be etched and printed. (Drawn after an image of the original of 1826.)

Copyright © David Morrish.

William Henry Fox Talbot (English: 1800–1877) is credited with the development of negative/positive photography. He made multiple positive prints from the paper negatives he produced in his “mouse-trap” cameras. In 1844, Talbot was the first to publish a book illustrated with photographs. The Pencil of Nature contained actual tipped-in salt prints, which, much to Talbot’s dismay, proved to be impermanent. He sought another way of making a more stable photographic image. The well-established fact that ink on paper was permanent led him to explore the idea of photographically producing etched plates that could be printed. In 1852, Talbot found that normally soluble colloids such as gum arabic, albumen, and gelatin become insoluble when mixed with potassium dichromate and exposed to light. Utilizing this hardening or tanning effect, Talbot developed an etching resist over which he used a screen of black crepe to help with the translation of tonal values in the etched plate. This negative screen (a network of crossed lines) is the forebear to the positive screen used in modern rotogravure. Talbot’s photoglyphic engravings are sharp and detailed but lack the smooth gradation of tone associated with other photographic representations, including his own calotypes (Figure 1-2). He continued to improve on his technique as he moved from iron plates to copper and etched with ferric chloride instead of platinum chloride. He also etched with three baths and greatly improved the tonal scale on later tests. He felt the resulting prints were well suited to book illustration and had good commercial value (Buckland 1980, p. 114).

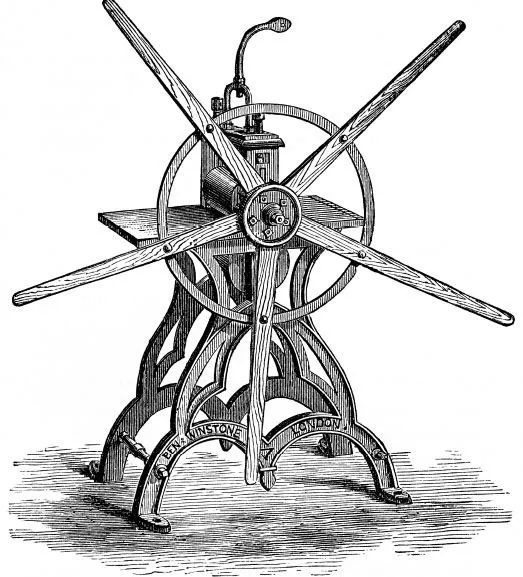

Figure 1-2 Henry Fox Talbot used an intaglio press very much like this late 19th century press.

Illustration by W. L. Colls, © Iliffe & Son, London, 1890.

In 1855, Alphonse Louis Poitevin (French: 1819–1882) patented the first carbon process, in which he added carbon black to the colloid (gelatin) and dichromate mixture and coated it on paper. Again, the image left on the paper was formed by the insolubility of the exposed gelatin (Crawford 1979, p. 70). By 1856, eight different carbon processes were announced, but none were capable of capturing a full and gradual tonal scale. After numerous failed attempts, Joseph W. Swan (English: 1828–1914) solved the tone reproduction problem in 1864 when he and John W. Sawyer patented their version of carbon-gelatin tissue and the carbon transfer process. Adolphe Braun of Dornach (Alsace) bought the rights to this patent and began publishing carbon transfer reproductions of paintings and Old Master drawings (Crawford 1979, p. 72). In 1858, Talbot changed his process by adding a rosin aquatint to the surface of the exposed gelatin prior to etching the plate. This was then etched with ferric chloride through the underlying bichromated gelatin layer. He was able to obtain richer plates with more tonal graduation due to the delicate grain (Mertle and Monsen 1957, p. 325).

Early printers were driven to search for a more permanent image-making process due to the impermanence of silver-based images such as salt and albumen prints. There was also a need to reproduce photographic images, either as independent entities or as integral parts of publications. The fact that printing ink on rag paper was archival was key to those who tried to perfect the photogravure process.

Charles Nègre (French: 1820–1880) produced the first published reproduction of a small “proto-photogravure” within a page of text in 1854 in La Lumière. From 1856 to 1867, Nègre was competing in a drawn-out competition sponsored by Honoré d’Albert, duc de Luynes for the best way to reproduce an image in a totally mechanical way. Nègre had to submit a sampler showing a range of textures and tonalities. His gravure submission came in second to Poitevin’s winning planographic entry because the jury suspected Nègre used hand-work on his plate and because his process was slow and complicated. Nevertheless, the Duc de Luynes appreciated Nègre’s work and commissioned him to produce a large work called La Mer Morte (started in 1865 and completed in 1868). Nègre also produced large-scale architectural studies of the restoration of Chartres cathedral using his gravure-based process. Although very detailed and richly printed, these images were not like modern photogravures in their technique nor their tonal range. They lacked the smooth transitions from one tone to another. Some examples seem almost posterized. They were also heavily retouched. Façades were lightened, shadows were opened up with hand work, and skies were added in a painterly fashion. A key difference in the technique was that the images were printed from steel plates rather than copper. Steel plates have a self-graining effect when etched, eliminating the need for an aquatint. In contrast, the copper plates used for classic photogravure require the application of a dust-grain aquatint in order to maintain tone.

Although these developments formed the foundation of modern photogravure printing, the process as we know it today was actually devised in 1879 by Karl Wenzel Klič (Karel Václav Klitsch) (Czech Republic then Arnau: 1841–1926). Utilizing an asphaltum aquatint under the sensitized and developed gelatin-coated pigment paper resist, he combined Talbot’s etching procedure with these new materials to produce a true photogravure print. Klič’s procedure differed from Talbot’s in that the resinous powder was applied directly to a copper plate and then covered with the sensitized carbon tissue. The Talbot-Klič process of photogravure was born. After this point, the production of hand-pulled, flat plate photogravures continued to improve slightly using a technology that has not appreciably changed since its invention.

The main commercial development was the advent of rotogravure, a mechanized commercial process invented by Klič and mastered as early as 1890. Rotogravure is still used today by the printing industry. For the purposes of this text, and the discussion of photogravure as an artist’s medium, we will not address the particulars of rotogravure.

ARTIST-PRACTITIONERS

Historically, the photogravure process as used by printers and publishers was determined by the balance between image quality and production economy. Meanwhile, artists wanted to reproduce their work by capitalizing on photogravure’s inherent aesthetic qualities. Most had previously worked with platinum, albumen, or silver-gelatin. The photogravure print more closely resembled a mezzotint than a halftone and therefore had more cachet as a fine print when included in a publication. It was clear that no other reproductive medium could come as close to the artists’ aesthetic vision. The appreciation of the malleability of the medium superceded its amazing verisimilitude and soon artists were using photogravure to express themselves in ways that traditional photographic means could not. Many photographers became printmakers when they realized this potential.

Peter Henry Emerson (American working in Britain: 1856–1936), the preeminent figure of the naturalistic school of nineteenth-century photography, created many publications that utilized photogravure to echo his atmospheric platinum prints. His pale, low-contrast, but fully toned images were reproduced with photogravure more and more successfully from one publication to the next. On English Lagoons (1893) was printed by Emerson from plates he etched himself. Marsh Leaves (1895) was his last self-produced album of gravure prints. In his book Naturalistic Photography (1889), Emerson states his preference for photogravure over other photographic media, including platinum prints. He states that it is the ideal medium with which to present pure photography because of the flexibility of choice in ink and the range of available papers (Coe and Haworth-Booth 1983, p. 100). The Compleat Angler, or the Contemplative Man’s Recreation. Being a discourse of Rivers, Fish Ponds, Fish and Fishing written by Izaac Walton, and Instructions How to Angle for a Trout or Grayling in a Clear Stream by Charles Cotton, was reprinted in its 100th edition in 1888 by the publisher/editor R. B. Marston. This two-volume publication contained 54 photogravure illustrations on special India paper, of which 27 were by Emerson. Emerson made the original negatives along the Lea River in the spring of 1887. The resulting publication was an outstanding example of Emerson’s aesthetic and skill (Figure 1-3 and Color Plate 1).

In 1968 and again in 1877, before Pictorialism became the dominant aesthetic posture of artist-photographers, Thomas Annan (Scottish: 1829–1887) was commissioned by the Glasgow Improvement Trust to photograph the closes, wynds and buildings slated for demolition in the city center. The Old Closes and Streets of Glasgow was first published as carbon prints but was republished in 1900 as Old Closes and Streets, a Series of Photogravures, 1868–1899, in two editions of 100, each containing 50 photogravures, some of which were heavily manipulated (Figure 1-4). Annan’s work stands out for its rich clarity and skillful printing by James Craig Annan (1864–1946), Thomas Annan’s son. James Craig was the printing firm’s expert on photogravure, having been tutored in the process by Klič himself (Crawford 1979, p. 250). J. C. Annan’s own work appeared in a portfolio entitled Venice and Lombardy: A Series of Original Photogravures, published in 1898 in an edition of 75 copies (Figure 1-5). He is also credited with the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. A Brief History

- 2. Making the Film Positive

- 3. Sensitizing the Gelatin Tissue

- 4. Preparing the Copper

- 5. Exposing the Gelatin Tissue

- 6. Adhering and Developing the Gelatin Tissue

- 7. Preparing to Etch

- 8. Etching the Plate

- 9. The Printing Process

- 10. Alternative and Historic Methods and Materials

- 11. Directions for the Home Manufacture of Carbon Tissue for Photogravure Printing

- Appendices

- Reference Materials (Bibliography)

- Contributors

- Glossary

- Index

- About the Authors