![]()

PART I:

COMMUNITY ACTION RESEARCH: BENEFITS TO COMMUNITY MEMBERS

![]()

Issues Facing the Dissemination of Prevention Programs: Three Decades of Research on the Adolescent Diversion Project

Marisa L. Sturza

William S. Davidson II

Michigan State University

SUMMARY. This paper argues that the issues facing effective prevention programs when they embark on dissemination, implementation, and routinization have been largely ignored by the field. Through the example of the Adolescent Diversion Program, these issues are illustrated and discussed. Four sequential longitudinal experimental studies are summarized as a context for the discussion of dissemination issues. In each case, the alternative preventive program is demonstrated to be more effective than traditional approaches. Challenges to widespread implementation of effective prevention programs are then discussed with a call for the field to add such issues to its scientific agenda.

[Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> ©

2006 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.] KEYWORDS. Prevention, prevention program, juvenile delinquency treatment, dissemination

After nearly 30 years of operation, the Adolescent Diversion Project (ADP) has continued to divert youth from traditional juvenile court processing as a method of preventing future delinquency. The program has been focused on intervention methods which create an alternative to juvenile court within a strengths-based, advocacy framework (e.g., Davidson et al., 1990). In multiple randomized trials, ADP has demonstrated that youth exposed to alternative preventive interventions have lower rates of recidivism compared to youth who have either undergone traditional juvenile court processing or been released without further intervention. Further, the ADP costs a fraction of what traditional court processing does (Davidson et al., 1990; Davidson et al., 2000, Davidson & Redner, 1988; Smith et al., 2004). Also, the ADP has found that youth participating in the program have exhibited increased involvement with families, schools, employment, and reported overall positive experiences with the intervention (Davidson et al., 1990; Davidson et al., 2000). In addition, ADP has demonstrated that students working as advocates have reported increased political commitment (Angelique, 2002). For the purposes of the present paper, the outcomes of reduced recidivism rates and cost will be focused on. The present paper will provide a description of the history of the ADP, a summary of prior research on the program, and outline challenges facing effective alternative prevention models as they seek adoption and routinization.

HISTORY OF THE ADOLESCENT DIVERSION PROJECT (ADP)

Research on the ADP model was first conducted in the 1970s and replicated/extended through the 1980s and 1990s (Davidson et al., 1977; Davidson et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2003). The original prototype continues to operate in partnership with a local county in order to provide prevention services for over 100 youth per year. Diverting youth from traditional juvenile court services is the foundation of ADP. This notion of youth diversion originated out of the President’s 1967 Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice. This commission argued that the traditional system was so ineffective that alternatives had to be considered (Davidson et al., 2000; Gensheimer et al., 1986; President’s Commission, 1967). The historical context for the development of the ADP model is important to understand. At the time of its inception, juvenile delinquency was a national priority. Further, it had been argued that the juvenile justice system was expensive, inhumane, and ineffective (Krisberg & Austin, 1976). It had even been argued that the traditional court increased future delinquency (e.g., Gold, 1974).

COMPONENTS OF ADP

Given the zeitgeist present at the time ADP was developed, it was clear that an alternative was needed. What was less clear was what should be done as an alternative. In other words, it was clear what not to do; it was less clear what to do. There were several prominent areas of research which were key to the original development of the ADP prevention model. First, as mentioned above, the creation of an alternative to the justice system (which became known as diversion) was recommended. Formally, the tenets of symbolic interactionism and labeling theory were central to design of the model. Second, the goal of providing preventive interventions which would minimize the negative effects of labeling and enhance positive expectations was included (e.g., Gold, 1974; Becker, 1968). The direct implication was that preventive interventions would best take place outside the formal court system and that the content of intervention should be positive in its focus. Third, at the time, a literature was beginning to develop which demonstrated that relatively intense interventions were more likely to be effective (Davidson et al., 1989; Lipsey, 1992). Finally, alternative preventive interventions (as is almost always the case) were expected to cost less.

Each of these factors played a key role in the development of the ADP model. The original preventive model occurred outside the juvenile justice system, accepting referrals from the juvenile division of a local police department as an alterative to formal prosecution. This structure had two advantages. First, it avoided the potential risks of overidentifying “potential delinquents” or “pre-delinquents” and ensured that the youth involved were truly at risk of official delinquency. Avoiding net widening was an important consideration (Sheldon, 1999). Second, it insured that the preventive intervention was truly an alternative to the formal system and hence preventive in its focus. This can be thought of as the systems level characteristics of this preventive program. Additionally, the preventive model involved individual-level intervention activities which were specific, positive, and intense. Originally, the promising alternatives of behavioral approaches (e.g., Patterson, 1971) and child advocacy (e.g., Davidson & Rapp, 1976) formed the basis of the individual-level intervention which took place in the diversion context. While relatively new on the scene of delinquency intervention at that juncture, both approaches had demonstrated considerable empirical promise (e.g., Davidson & Seidman, 1976), provided specific prescriptions for forming a preventive intervention model, and were strengths-based in their focus.

Finally, the intensity and cost of the preventive intervention had to be addressed. A related set of events was important in the construction of the ADP model. At the time, the systematic use of alternative person power groups (e.g., Rappaport et al., 1971) was achieving considerable promise. Further, the use of such groups as students and/or volunteers as change agents had demonstrated promising results while providing an inexpensive alternative for providing intense services (e.g., Tharp & Wetzel, 1969). Within this historical and theoretical context, the ADP prevention model was created. It involved the use of trained college students as change agents using behavioral and advocacy approaches in intense one-on-one preventive interventions in a diversionary, alternative context.

The major purpose of this article is to articulate the challenges successful prevention programs will face as they move from demonstrating their efficacy towards adoption as usual practice. To date, the preponderance of research on prevention has been focused on demonstrating efficacy. It has often been assumed that if effective alternatives are developed and demonstrated, widespread adoption will follow and routinization will follow (e.g., Mayer & Davidson, 2000). It is now clear that this is not the case, particularly as preventive alternatives are truly alternative and effective. The balance of this article will begin to elucidate the issues involved in these issues using the case of the ADP as an example. In order to set the stage for this discussion, the empirical history of ADP will be briefly reviewed for the reader not familiar with this empirical history. A relatively brief description of the outcome results of the ADP will be included here. For the interested reader, past studies presenting the results of the ADP over the past 25 to 30 years are provided in the Appendix.

OUTCOME RESEARCH ON THE ADP PREVENTION MODEL

Research evaluations of the ADP project have been broken up into four distinct phases (Davidson & Redner, 1988; Davidson et al., 1987; Smith et al., 2003). The purpose of the multi-phased project development has been to demonstrate reduced recidivism rates (Phase 1), determine the integrity and relative efficacy of the intervention components (Phase 2), examine the relative effectiveness of the types of advocates (Phase 3), and replicate the model in an urban setting allowing direct comparison of the model to usual processing (treatment as usual control) and outright release (no treatment control) (Phase 4).

Phase 1

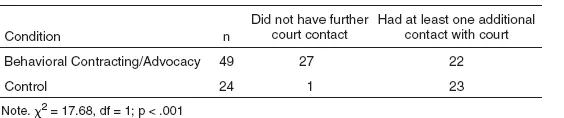

In Phase 1, 73 youths participated, 84% who were male and 67% who were Caucasian. The conditions were dichotomized into treatment (ADP preventive intervention) and control (diversion without services). Preventive interventions were delivered one-on-one by college students (8 hours of intervention in the youth’s environment per week), who were trained (80 hours of training) and supervised (two hours per week of supervision) in the use of behavioral contracting and child advocacy. The ADP group demonstrated significantly reduced recidivism rates when compared with the control group at both one and two-year follow-ups (Davidson et al,. 1977). While these results lent support to the ADP model of behavior contracting and advocacy, this was a preliminary study. The number of participants was relatively small and only a single city was involved. The need for systematic replication seemed paramount (see Table 1).

TABLE 1. Phase 1 Two-Year Follow-Up Recidivism Occurrences

Phase 2

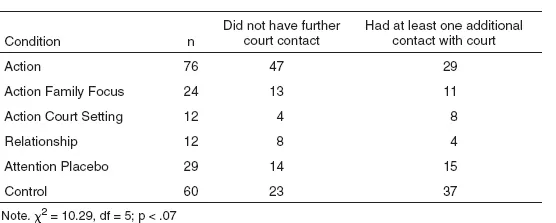

Phase 2 built upon the treatment versus control design of Phase 1, but instead expanded the number and type of conditions in order to more specifically test the effects of the preventive intervention components. In Phase 2, 228 youths participated. The participants were 83% male and 74% Caucasian. The youths were randomly assigned to one of six conditions: Action (AC), Action Family-Focus (AC-FF), Action Court-Setting (AC-CS), Relationship (RC), Attention Placebo (APC), and Control (CC).

The Action, Action Family-Focus, and Action Court-Setting groups all involved advocacy and behavioral contracting. The difference between these three conditions was that the Action condition used behavioral contracting and advocacy to focus on all domains of the youth’s life (e.g., family, school, peers, and employment), the Action Family-Focus used these techniques to focus exclusively on the youth’s family, and the Action Court-Setting used these techniques within the context of court supervision. As a strategy to directly examine the effects of conducting preventive interventions outside the court system, student change agents in the Action Court-Setting group were trained by ADP staff, but supervised by juvenile court staff. In many ways, the Action Court-Setting group was the beginning of examining dissemination issues. Specifically, the question of what would happen to the efficacy of the preventive model when turned over to the existing system for operation was investigated.

The Relationship condition focused specifically on the relationship between the advocate and the youth without the advocacy and behavioral contracting components. The Relationship condition was a direct attempt to examine the impact of the relationship component of the preventive model. In other words, this phase explored what the effect would be of the relationship components of the intervention when they were evaluated in isolation.

The Attention Placebo condition did not have a structured model of intervention and was included in Phase 2 research to determine whether the Action conditions produced different outcomes than a nonspecific intervention. Finally, the Control condition was included to provide a treatment as usual control (Davidson et al., 1990).

Results from Phase 2 demonstrated that the only condition that significantly reduced recidivism when compared to the Attention Placebo group was the Action condition. The Action Family-Focus and Relationship groups were both superior to the treatment as usual control, but not more than the attention Placebo group. The Action Court-Setting group demonstrated the highest rate of recidivism, higher than the control (Davidson et al., 1990) (see Table 2).

Phase 3

After testing the relative efficacy of intervention components, Phase 3 sought to investigate whether the type of change agent was critical. University students had been enlisted in the previous two studies as advocates, but Phase 3 compared them to both community college students and general community volunteers. In Phase 3, 129 youths participated who were primarily male (83.9%) and Caucasian (70.2%). They were randomly assigned to university students, community college students, or community volunteers. Results from Phase 3 demonstrated that all groups were more effective than a treatment as usual control in reducing recidivism, indicating that the model was robust across type of change agent. The results also showed that the university students had more knowledge of the model, spent significantly more time with their youth, and the youth in this group reported having more positive experiences with their advocates. Evaluation of change agents in Phase 3 found that although there were significant benefits to using university students over the other two groups, community college students and community volunteers may also be effective advocates for this population (Davidson et al., 1990). In terms of recruitment, retention, and supervision, university students cost substantially less than the other two groups (see Table 3).

TABLE 2. Phase 2 Two-Year Cumulative Follow-Up Recidivism Occurrences

Phase 4

Phase 4 research examined three additional issues. First, it was important to replicate the preventive model beyond the medium-sized city populations of Phases 1 through 3. Second, it was important to examine the ADP model in comparison to treatment, as usual control as well as no treatment control within the same study. Third, it was important to see if the ADP model would be effective when implemented by paid professional staff. In Phase 4, the ADP model was implemented and tested in a large urban city (n = 395) with a population that was 84% male, and 90.6% African American. Youth were randomly assigned to either the ADP model, diversion without services (no treatment control), or traditional juvenile court processing (treatment as usual control). The urban replicate of ADP included both...