- 100 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tourism and Development in the Third World

About this book

What is the thruth behind the paradise beaches in travel brocures? What can a developing country do when one exotic holiday seems much like another, when political instability or environmental disaster can deter tourist for years, when the tourism industry slips into foreign control?

Tourism and Development in the Third World assess the diverse social, economic, and environmental factors which impact on the Third World. Illustrating the analysis with cases which range across tourism in game parks, sex tours and the after-efects of political turmoil, the book explores ways of managing tourism as a resource and evaluates its long-term contribution towards national development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tourism and Development in the Third World by John Lea in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

General introduction

International tourism has been described by Louis Turner as ‘the most promising, complex and under-studied industry impinging on the Third World’. It is only recently, however, that tourism has begun to take its place besides more traditional economic activities in the textbooks on Third World development. When one examines the large and rapidly growing literature on tourism, some interesting trends and divisions emerge. Up to twenty years ago all studies tended to assume that the extension of the industry in the Third World was a good thing, though it was acknowledged that there were a number of associated problems to be overcome in time. This picture changed in the 1970s with academic observers taking a much more negative view of tourism’s consequences to the point of forthright criticism of the industry as an effective contributor towards development.

A peculiar pattern of rich, temperate, countries of origin connects tourists to a much larger number of less affluent and warmer destinations comprising a ‘pleasure periphery’ on a world scale. This has been identified as a band of host countries stretching from Mexico and the Caribbean to the Mediterranean; from East Africa via the Indian Ocean and South-east Asia to the Pacific Islands; thence back to Southern California and Mexico. Most of the tourism in this periphery is actually confined to its most developed parts such as Singapore and Hawaii, emphasizing the fact that the industry, in common with other major sections of world trade, flourishes best in the more economically advanced countries. It should also be noted that most tourist movements are not international at all and are confined to domestic travel in the rich western nations.

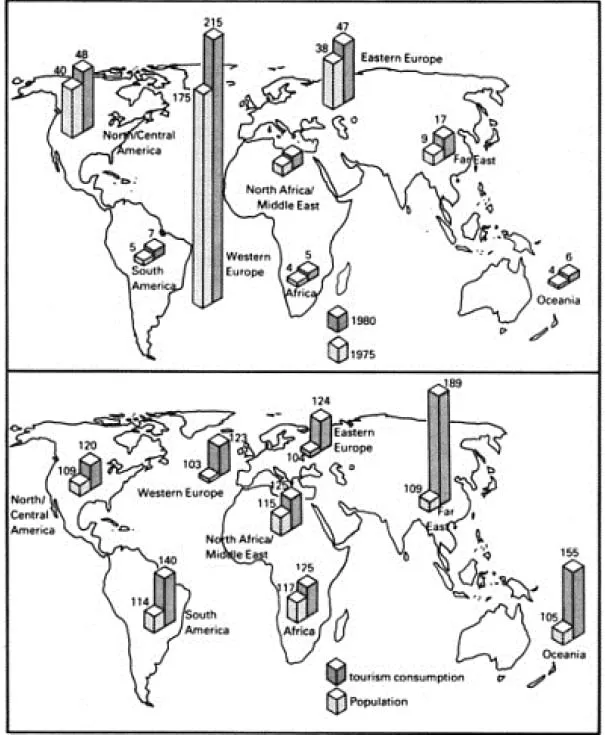

Another way of illustrating international tourism is to portray the world as eight geographic regions (Figure 1.1). Regional growth in tourist arrivals is shown in the top map as totals of visitors for the years 1975 and 1980, confirming that the largest markets are western and eastern Europe and north-central America. The picture changes in the bottom map where the rate of regional population and tourism growth is measured for the same period. Here we see that the largely peripheral regions of the Far East, Oceania, and Latin America are outstripping the rest in the pace of tourism development.

In terms of sheer size international tourism accounts for about 6 per cent of world trade and more than 300 million tourist visits annually. One projection expects visitor travel to rise to 500 million by the year 2000. As far as individual developing countries are concerned some, such as the small islands in the Caribbean, are highly dependent on foreign tourism for export income, whereas large states like Brazil or India are much less vulnerable and more diverse in their earning capacity. Others, like Tunisia and Sri Lanka, have experienced a roller-coaster effect as the rapid boom in tourism of the 1970s has been replaced in recent years by falling visitor numbers and increased competition from alternative destinations.

International tourism is a volatile industry with potential visitors quick to abandon formerly popular destinations, like Beirut or even Greece, because of threats to health or security. It will be clear by now that a range of pressures and peculiar influences affect tourism’s role in development and distinguish it from the conditions governing the agricultural and mineral exports making up the bulk of Third World trade. Of special significance here is tourism’s classification as an invisible export industry, along with banking and insurance where there is no tangible product, and the fact that tourists have to travel to a destination to make personal use of the facilities they desire. This means that few freight costs are usually incurred by the Third World host country because the means of travel is generally foreign-owned. In addition there are obviously different kinds of face-to-face contact between the visitor and host society.

Figure 1.1 (top) Regional growth in tourist arrivals 1975 and 1980 (millions of visitors); (bottom) Growth in regional population and tourism consumption 1975–80 (1975 = 100)

Data Source: Senior (1982: 70–3)

There is no other international trading activity which involves such critical interplay among economic, political, environmental, and social elements as tourism and this is demonstrated in the large and rapidly growing literature. The temporary presence of mainly white and relatively wealthy foreigners in tourist hotels, situated at scenic locations in some of the world’s poorest countries, is a scenario fraught with risk and opportunity. In this book we will investigate how tourism contributes to development in the Third World and outline some of the approaches used to understand and categorize the industry as a distinct form of economic activity. Case studies selected from the major tourist regions will draw together some of the more important lessons from current experience.

Some definitions

Labels like ‘tourism’, the ‘Third World’, and ‘development’ are part of popular terminology and capable of many different meanings according to the purposes for which they are used. The word tourism for example is capable of diverse interpretation with one survey of eighty different studies finding forty-three definitions for the terms traveller, tourist, and visitor. Perhaps the most useful and comprehensive definition for our purposes is the one suggested by Erik Cohen who describes the tourist as ‘a voluntary, temporary traveller, travelling in the expectation of pleasure from the novelty and change experienced on a relatively long and non-recurrent round-trip’.

The term ‘Third World’ is equally capable of confusion and is meaningful only when contrasted with industrialized nations (the so-called First and Second Worlds) of the western democracies and eastern socialist countries (see John Cole’s book in this series). We will follow the approach used by Stephen Britton who uses the terms ‘centre’ or ‘metropolitan’ for the core western democracies of North America, Europe, Japan, and Australasia but excludes the Eastern European socialist states. The remaining countries are collectively described as ‘Third World’, ‘periphery’, and ‘developing’ with the general exception of mainland China, Cuba, and Vietnam which have adopted socialist forms of government. The reason for leaving the socialist countries out of the general definitions will be apparent when we examine theoretical approaches towards tourism and development in chapter 2.

Development is the most slippery concept of them all and is commonly used in many different ways as well as having changed in meaning over time. John Friedmann has identified at least five dimensions:

- To suggest an evolutionary process of a positive kind such as rising incomes.

- In association with words like under, over, or balanced, suggesting it has a structure.

- As the development of something like a society, a nation, or skill.

- As a process of change.

- As the rate of change at which the processes occur over time.

In the past the measurement of Third World development was limited to certain economic indicators such as per capita income (averaged over the whole population) and gross national product (GNP). This said nothing about how wealth was distributed, nor did it identify the status of important social factors like health, education, and housing. Today development is seen in much broader terms recognizing that increases in national wealth may benefit only a small élite and can, in extreme cases, hide a decline in living standards for much of the population. Some international agencies, such as the World Bank, regularly publish comparative social indicators covering many useful criteria which can be used in conjunction with the more traditional economic measures to provide a more balanced picture.

In this book we will consider the contribution of tourism to Third World development from important historical, economic, political, social, and environmental perspectives in recognition that economic benefits from the industry in the host countries can be outweighed by less obvious disbenefits in other areas. It is open to question, for example, whether locating luxury casinos in very small Third World countries, with every possibility of associated crime and prostitution, can be judged as development from the viewpoint of most of the population. Similarly, spending huge sums on a new international airport may put a small island on the world tourism map but has every possibility of reducing essential investment in other areas and making it easier for skilled islanders to leave their homes for higher incomes elsewhere. The answers to these dilemmas are rarely clearcut and have led to a serious reappraisal of international tourism in much of the Third World.

Primary elements of international tourism

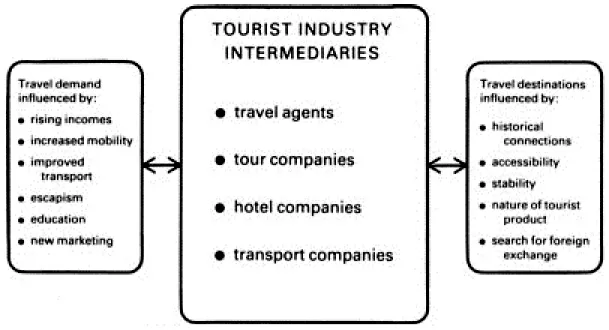

It is very likely that the thoughts which most of us have about tourism are centred on the travellers themselves or on a variety of exotic destinations, without considering who actually controls the international market. We take for granted today the existence of travel agents and tour, hotel, and transport companies which intervene between the would-be tourist and a chosen destination. These intermediary companies created and now control a global mass tourism market through their transnational operations in origin and destination countries. The largest have expanded vertically to the point where they have interests in all major sections of the industry and are not answerable to policies determined by any single government.

This evolution of tourism into a business organized along the lines of transnational manufacturing industry has brought with it specialized marketing techniques like the packaged tour, fly-now pay-later deals, and the powerful persuasion of radio, television, and the print media. The modern tourism product is not confined to travel and accommodation but includes a large array of servicing activities ranging from insurance to entertainment and shopping. Even the creation of the desire to travel is covered and, we will demonstrate, is responsible for the emergence of a travel mythology which often bears little resemblence to reality.

Figure 1.2 summarizes the major influences on both ends of the tourism experience and emphasizes the strategic position of the intermediary companies. There will be an opportunity to examine some of these items in much greater detail later but they are listed here to give an early idea of the threefold division involved. Certain company groups like airlines and banks have used their strategic positions to expand into many sections of the industry, minimizing the functional divisions between activities like marketing, accommodation, and travel. Differing explanations of how this arrangement works in practice and its effects on Third World destinations will be examined in chapter 2.

Figure 1.2 Primary elements of the international tourism industry and influences on the market

Several preliminary conclusions can now be made about the nature of international tourism and its role within the development of the Third World.

- International tourism is unbalanced with most power and influence being held by intermediary companies controlling the metropolitan origins of Third World tourists.

- The international tourism experience is often inequitable with foreign demands for a luxury being met by local requirements for hard currency, in circumstances where few alternatives exist.

- Few of the factors influencing tourism in poor host countries relate to the tourist industry alone; most of them are symptomatic of a general condition of underdevelopment.

- Few opportunities exist for Third World host countries to cut out the intermediaries and deal with their sources of tourist supply directly.

Tourism’s costs and benefits

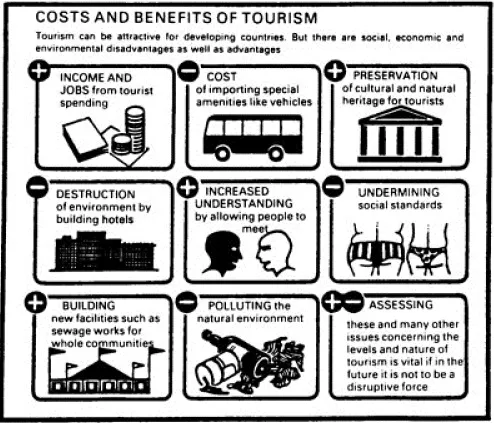

Because few of the poorest developing countries have obvious income-earning alternatives to tourism, it is sometimes adopted only as a last resort. However, with formerly valuable exports, like cane sugar, suffering from the general fall in world commodity prices and competition from larger and more efficient agricultural producers, tourism in these circumstances is a mixed blessing and demands a careful accounting of the complex pattern of costs and benefits involved. Some of the more obvious of these are found in the United Nations diagram contained in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Costs and benefits of tourism

Source: United Nations Environment Program (1979), in Senior (1982)

This complex matrix of advantages and disadvantages ensures that governments must face an unenviable task of trying to weigh gains from new income and employment against certain less direct and long-term losses. It is difficult indeed for politicians to reject a new hotel project, for example, on environmental or social grounds when construction means present jobs and political prestige. In fact it is difficult to oppose any substantial foreign investment in situations where the few competing development prospects may actually have worse impacts on the host community than those associated with tourism. How can one reasonably hope to choose between the competing merits of plantation agriculture, export processing zones for manufacturing industry, or tourism, when any or all of these things are actively sought by Third World countries in a highly competitive environment?

Clearly then, there is a difficult range of questions to answer and very little likelihood of finding general solutions which will cover the widely differing circumstances of individual countries. A primary aim of this book is to introduce the extent and characteristics of the issues involved to enable a better understanding and critical appraisal of the existing situation. It should be emphasized that decisions about development in the Third World itself are a local responsibility and where solutions to tourism problems are raised in this book, it is done to facilitate this process. International tourism is almost by definition controlled by interests outside the peripheral host countries and is only marginally susceptible to the exercise of local sovereignty.

Organization of the book

Chapter 2 examines two broadly different ways of thinking about international tourism as a complex activity. One is a view which places great importance on the historical background of Third World under-development and considers today’s economic realities in terms of a global system. The other identifies the main elements of international tourism as a series of functional parts without posing the underlying question why the industry possesses its present characteristics. The recent development of resort hotels and casinos in the South African ‘homelands’ and surrounding black states (also known as the southern African ‘pleasure periphery’) is examined as a case study.

Chapter 3 looks closely at the nature of tourism demand in the Third World and the supply of accommodation and facilities for the visitor. It is helpful here to think of demand as a dynamic process consisting of various influencing factors (Figure 1.2), types of tourism, and kinds of tourists. The supply of tourist facilities at the destination can be thought of as an evolving process, as well as a more static activity producing built accommodation, attractions, transport, and all kinds of support services. The dramatic impact of the 1987 military coups on the Fijian tourist industry forms the case study.

Chapter 4 deals exclusively with the economic impacts of tourism and is subdivided into sections looking at some of the economic characteristics of the industry, its economic benefits, and costs. The misuse by consultants of a well-known analytical technique in a study of Caribbean tourism forms the case study. Chapter 5 is divided into two parts dealing with environmental and social impacts of the industry at Third World destinations and case studies examine visitor management in an East African game park and the effects of sex tourism in South-east Asia.

Lastly, it is important to consider the sort of national planning issues facing a host country government determined to promote tourism as a development strategy. Among the most important of these are the role of government itself and the possibilities for public or community participation in making significant decisions. The latter concern goes much further than seeking more local (Third World) participation in the decisions affecting the industry and covers ways in which ordinary people may be included in the decision-making process, because it is they who are most affecte...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- 1 General Introduction

- 2 Conceptualizing Tourism’s Place in Development

- 3 Tourism Demand and the Supply of Facilities

- 4 Tourism’s Economic Impacts

- 5 Tourism’s Environmental, Social, and Cultural Impacts

- 6 Planning and Management of Tourism

- Review Questions, References, and Further Reading