The notion that intergroup contact can improve intergroup relations is a deceptively simple idea with strong intuitive appeal. Indeed, this basic notion became a fundamental cornerstone of twentieth-century policymaking, at least in principle, as the world’s economies and interests became increasingly intertwined and co-dependent. Explicit contact goals are now formally enshrined in our most important international agreements. For instance, in the wake of World War II the newly-formed UNESCO constitution famously declared that:

But we are not solely concerned with contact between nations. Indeed, this same post-war period also bore witness to remarkable social changes within societies, such as the end of apartheid in South Africa, educational and military desegregation between races in America, and relative peace in Northern Ireland after 40 years of The Troubles. Many of these (largely) resolved conflicts were the direct result of formalized and often legally enforced imperatives for increased contact, directly rooted in empirically-based recommendations by empiricists (see Cook, 1957). Although well-intentioned, these policies were not, however, generally implemented in ways that maximized the benefits of contact (see Cook, 1979; Stephan, 2008). Rather, the historical and empirical record makes clear that contact does not universally improve relations, but can also exacerbate problems and intensify strife. The simple premise that contact improves intergroup attitudes is therefore not as straightforward as it would at first appear. Put simply, contact is no panacea for prejudice (see Hewstone, 2003).

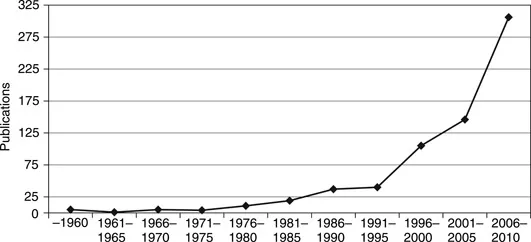

For this reason the empirical scientific evidence has become crucial in understanding whether and how contact works, in addition to mapping out its boundary conditions. Fortunately, this literature is now rather sizeable. Relative to other topics on intergroup relations, interest in contact peaked in the 1950s and 1960s before evidencing decreased share in the market-place of ideas (i.e., psychology journals) through the 1970s to 1990s (Brown & Hewstone, 2005). The last edited volume on this topic, drawing together international scholars to reflect on the contact literature, is now 25 years old (see Hewstone & Brown, 1986a). Since that time an undeniably large body of research has accrued that speaks to the benefits of intergroup contact, advancing the field not only theoretically but also in terms of methodology and application. In recent years, intergroup contact has recaptured the passions of psychologists at a truly impressive rate. As of December 2011, literature searches for the terms “intergroup contact” or the “contact hypothesis” as keywords in psychology journals revealed over 675 papers, with two-thirds of these papers published since 2000 (see publication trends in Figure 1.1). As is evident from these trends, intergroup contact is a rapidly expanding field. The present volume brings together leading researchers in the field to provide a much-needed update on the latest psychological advances in understanding contact as a prejudice-reduction strategy. Before turning to these recent advances, however,

we first outline the fundamental ideas outlined in what theorists originally termed the “Contact Hypothesis.”

Intergroup contact theory

Serious interest in the empirical study of the effects of contact on outgroup attitudes began to take root in the 1940s through the early 1960s. Early work by sociologist Robin Williams (1947, 1964) and social psychologist Stuart Cook (1957) was well-established at the time, but arguably the most influential voice came from social psychologist Gordon Allport’s (1954) seminal book The Nature of Prejudice, in which he devoted an entire chapter to contact. Analysis and synthesis of this body of work has been covered in depth elsewhere (see Amir, 1969; Brown & Hewstone, 2005; Hewstone & Brown, 1986b; Kenworthy, Turner, Hew-stone, & Voci, 2005; Pettigrew, 1998; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2005, 2006, 2011) and does not represent the goal of the present volume. From the start, Allport’s stated reservations about the ability of contact to reduce prejudice (see Hodson, Costello, & MacInnis, this volume) led him to propose four key conditions required to improve the likelihood of positive contact outcomes. These “optimal conditions,” as they have come to be known, emphasize primarily the structural features of the contact setting.

First, contact is optimized when it involves members of different groups who have relatively equal status in terms of power, influence, or social prestige in the contact context. This condition is, of course, difficult to satisfy, and groups of equal status can themselves become competitive in order to serve needs for distinct identities (e.g., Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Even the future prospect of equal group status can be perceived as threatening in contact settings (see Saguy, Tropp, & Hawi, this volume). Low-status Whites, for instance, may reject racial integration with low-status Blacks in the interest of maintaining a relatively more dominant position in the overall social hierarchy (Cook, 1957). Second, groups are encouraged to pursue common or shared goals. According to Allport (1954), “Only the type of contact that leads people to do things together is likely to result in changed attitudes” [italics in original] (p. 276). To illustrate this point, Allport suggested that athletic teams comprised of members from different racial groups should work toward a common goal (i.e., winning a game) that has nothing to do with race per se. He also reviewed research showing lower prejudice toward Blacks among Whites serving in mixed-race military units. Contemporary research confirms this intergroup contact effect among US soldiers recently serving in Afghanistan and Iraq: heterosexual military personnel who formed bonds with homosexual squad-mates were particularly likely to oppose the ban on open homosexuality in the military (Moradi & Miller, 2010). Third, cooperation (vs. competition) between groups is considered ideal. (Although groups can have divergent or distinct goals that can be mutually satisfied via cooperation, common goals and cooperation are generally correlated positively, with the benefits of contact most fully realized when these factors are congruent with one another – the pursuit of common goals through intergroup cooperation.) Fourth, socialized or institutionalized support for positive intergroup relations is posited to enhance both the likelihood of contact and the potential for positive outcomes. Institutional support can range from informal or implied social norms in support of contact to rules that are explicitly sanctioned or enforced by authorities to promote intergroup engagement.

Over time, researchers understandably elaborated the optimal conditions for contact. Somewhat ironically, this led to a decreased interest in the theory as the number of preferential pre-conditions became unmanageable and increasingly difficult to satisfy (Pettigrew, 1986; Stephan, 1987). Fortunately, interest in the theory surged again by the late 1990s and early 2000s (see Figure 1.1). Undoubtedly a key factor in this renewed enthusiasm was Pettigrew’s (1998) very influential and highly-cited paper, in which he revised and reformulated the Contact Hypothesis, breathing new life into the idea of contact as a means to reduce prejudice. In his analysis Pettigrew emphasized several factors of change induced by contact, including the opportunity to learn about the outgroup, and willingness to undertake a re-think of one’s own group, its attributes, values, and so on (i.e., ingroup reappraisal).

Recent meta-analytic summaries confirm the proposition that ignorance is reduced via contact, but the knock-on effects on attitudes are quite small relative to mediating factors such as reduced anxiety (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008). Although some research provides evidence of ingroup reappraisal following contact (e.g., Verkuyten, Thijs, & Bekhuis, 2010), Eller and Abrams (2004) found that ingroup reappraisal failed to materialize as an outcome in a longitudinal investigation. However, appraisals here were operationalized as ingroup identification and pride, yet ingroup appraisals can take other forms. Indeed, one of the benefits of cross-group friendships, especially indirect friendships through one’s ingroup friends, concerns the promotion of positive ingroup contact norms (Wright, Aron, McLaughlin-Volpe, & Ropp, 1997; Pettigrew, Christ, Wagner, & Stellmacher, 2007; see Davies, Wright, Aron, & Comeau, this volume). Such norm development, we argue, can involve reappraisals of the ingroup. To the extent that this is the case, ingroup reappraisals do result from intergroup contact, in the form of positive contact norm development. Lolliot, Schmid, Hewstone, Ramiah, Tausch and Swart, this volume, discuss this issue, and propose a role for ingroup reappraisal in “secondary transfer” effects of contact, whereby contact with members of one group reduces prejudices toward members of another (unrelated) group.

In considering how contact works, Pettigrew (1998) particularly emphasized the importance of affective ties derived through contact. Meta-analyses again bear out these predictions, with increased empathy and decreased anxiety largely explaining contact effects on attitudes (see Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008) relative to cognitive factors (see Tropp & Pettigrew, 2005a; see also summary tables in Hodson, Hewstone, & Swart, this volume). Arguably, Pettigrew’s reformulation re-kindled an earlier emphasis on affect, intimacy, and cross-group friendship through contact (see Cook, 1957). This should come as no surprise. After all, cross-group friendships optimally characterize desirable, positive, and intimate contact that occurs repeatedly through time and across situations. Through an emphasis on intimate contact and friendship, this reinterpretation of the Contact Hypothesis has reinvigorated interest in the potential of intergroup contact, and has generated impressive results (see meta-analysis by Davies, Tropp, Aron, Pettigrew, & Wright, 2011).

Finally, Pettigrew (1998) provided a theoretical model integrating several cognitive strategies known to improve intergroup relations. Specifically, he argued that initial contact is optimized when group representatives interact as individuals (through decategorization, de-emphasizing group memberships). However, once contact is established, salient group memberships are enhanced (through salient identities, or sometimes dual-group identities), with psychological union realized at the final step through shared social identity (recategorization as a common ingroup). Prior to this explicit theoretical synthesis these various theoretical camps appeared to be working at cross-purposes. However, by integrating these seemingly divergent psychological processes into a formalized contact model that incorporated a temporal component, Pettigrew’s line of thinking provided fertile theoretical ground for researchers, linking these cognitive approaches not only to contact but also to each other. Although this reformulation has received solid support in one study (Eller & Abrams, 2004), further research is sorely needed, particularly studies that test all of the components specified in the full model.

After a half a century of research, the field is now well-positioned to examine the impact of intergroup contact on attitudes both in the laboratory and the world more globally. In a comprehensive meta-analytic study, integrating and statistically quantifying results from empirical research from over 500 studies, Pettigrew and Tropp (2006) provided a clear and convincing case for the benefits of contact on intergroup attitudes. Overall, increased contact predicted less prejudice toward the contact group. The effect size (mean r = -.21) was small-to-medium by conventional standards (e.g., Cohen, 1988) and very reliable (p < .0001). To practitioners outside of the social sciences, this effect might appear unimpressively small. However, this contact-attitude association represents an effect size that is actually very common in psychology, a discipline explaining processes that are often extraordinarily complex and multifaceted.

To put this finding in context, consider first an extensive meta-analysis covering 100 years of psychology research more generally, that reveals that many important and meaningful effects in personality (mean r = .19) or social psychology (mean r = .22) fall in this range (Richard, Bond, & Stokes-Zoota, 2003). As Al Ramiah and Hewstone (2011) have noted, the size of the contact meta-analytic effect is comparable to that for the relation between condom use and sexually-transmitted HIV (Weller, 1993), or between passive smoking and the incidence of lung cancer at work (Wells, 1998). More to the point, however, is the fact that even small effects can have large outcomes (see Rosenthal, 1990, on the small but very meaningful effects of aspirin on reducing heart attacks). The substantial impact of small effects is particularly evidenced in social systems, such as those that promote intergroup bias. For instance, even the smallest degree of intergroup bias (e.g., 1 percent), situated in the context of a complex social system, can result in substantial group-based discrimination that is both meaningful and self-perpetuating over time (Martell, Lane, & Emrich, 1996). In sum, the fact that contact reduces intergroup prejudice, and that this effect is of similar magnitude to many of the most important psychological effects and interventions isolated by psychologists over the past century, is a theoretically important and practically significant finding.

But the potential benefits of intergroup conta...