- 261 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Knowledge in Organisations

About this book

First Published in 1997. The second in the readers' series, Resources for the Knowledge-Based Economy, Knowledge In Organisations gives an overview of how knowledge is valued and used in organisations. It gives readers excellent grounding in how best to understand the highest valued asset they have in their organisations.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Knowledge as Strategy: Reflections on Skandia International and Shorko Films1

Introduction

It has been argued by Bell (1979) and others that knowledge is the key resource of the post-industrial era and that telecommunications is the key technology. Employment categories have been reclassified to accommodate knowledge-working (Porat, 1977) and some analysts have argued that knowledge workers already form the dominant sector of western work forces (OECD, 1981). Computer scientists are prone to suggesting that knowledge-based systems can yield abnormal returns. For example, Hayes-Roth, Waterman and Lenat (1983) claim that knowledge is a scarce resource whose refinement and reproduction create wealth and, further, that knowledge-based information technology is the enabler that turns knowledge into a valuable industrial commodity. It could be argued whether knowledge is scarce, particularly as it can be created, reproduced and shared with as much chance of multiplying value as depleting it. Indeed economists who are concerned with allocation and distribution of scarce resources—and also who make assumptions about availability of perfect or costless information—do recognize these unusual qualities, classifying knowledge as a public good (Silberston, 1967). What is of interest, therefore, as the information society unfolds, is whether we can learn anything about knowledge, its value and knowledge-working from companies who are exploiting information technologies in new domains which have the character of knowledge processing.

The two case studies—Shorko Films and Skandia International—presented elsewhere in this volume provide such an opportunity. Ex post, they can be seen as examples of firms who built knowledge-based strategies which were enabled by IT. In Skandia’s case there is evidence that this was an explicit strategic intent in an information-intensive industry, namely reinsurance. In Shorko Films, the strategy could be better described as an emergent one, following the language of Mintzberg and Waters (1985), in the manufacturing sector, namely chemicals.

Skandia International built a risks/claims/premiums database to be shared and maintained worldwide and accessed by a corporate data communications network. Essentially they built an encyclopedia on all reinsurance business in niche sectors which was available to their underwriters anywhere who would use decision support tools and analysis and enquiry routines to explore patterns over time, work within parameters learnt and codified through experience and select profitable business taken at sensible prices. The explicit strategy, explained in the 1988 Annual Report, was the building of a platform of “know–how” and taking the lead in information and communications initiatives across the sector. Although in a somewhat esoteric industry, the Skandia case can be seen as an investment in product/market data or information or knowledge (a definitional conundrum to be discussed later). Knowledge-building through IT at Skandia International allowed them to pursue a niche strategy, specializing in those reinsurance classes which generated high information processing and required high analysis.

Shorko Films built a distributed process control system to try and optimize—or at least improve—factory efficiency in the plastic film-making business. Data was collected by a series of electronic nodes (in concept a network) on many parameters of the production process and optimization was pursued on-line and in-line. However, this crucially provided the opportunity to construct an historical database of product/process experience that could be analyzed to learn how to make further improvements in the process. Moreover, a better understanding of the interaction between process and product allowed Shorko to specify and develop new products, make product range profitability decisions and work out how to satisfy customers’ specialized requirements. Knowledge-building through IT at Shorko Films allowed them to pursue a competitive strategy of differentiation, exploiting their better understanding of process and its relationship to product, with the intent of yielding premium prices. Previously they had been caught on a seemingly hopeless task of low cost production demanded by the parent.

Both cases can be seen as demonstrations of Zuboff’s (1988) concept of “informating.” Indeed Shorko is a replication (or technology transfer) of the early directions Zuboff traced in the paper and pulp industry, and the IT investments began with an automating scope before the value of informating was recognized. The process management database becomes the model or image of the firm’s operation, the line operators become knowledge workers analyzing and manipulating information, the distinction between managers and workers becomes blurred and the nervous system is the distributed process control electronics. Skandia is not unlike Zuboff’s description of her financial services research sites. The database is not here the source of product development, but it is the generator of product decisions. The underwriters have developed new information processing skills using IT tools and the worldwide network is a transmitter and receiver of knowledge. These characteristics will be examined later.

More than “informating,” however, Skandia and Shorko can be seen as evolving cases of knowledge as strategy. This concept is not novel. After all, science and technology are a critical basis of competition in many industries, for example chemicals or electronics, and know-how is often the foundation in industries like engineering, contracting or consultancy. Indeed, innovation, today perceived as a generic need in all industries, can be seen as knowledge-dependent, whilst the concept of core competences, popularized recently by Prahalad and Hamel (1990) as an alternative strategic paradigm to conventional productmarket thinking, is close to the construct of know-how. What perhaps is interesting is that as information technology becomes pervasive and embedded in organizational functioning, new opportunities for building competitive strategies on knowledge are becoming apparent. This chapter therefore seeks to develop by induction some thoughts on knowledge as strategy. The vexed question of what is knowledge is a good starting point and an attempt is made to analyze and classify information systems from a knowledge perspective. Some observations on the strategic value of knowledge are made and thereby on the relative value of different types of information system. The two cases also are suggestive of what is required if knowledge is to be managed as a strategic resource and so a model of knowledge management is proposed and developed.

The concept of “knowledge as strategy” invites theorizing. Case studies such as these allow us to explore ideas, describe emerging phenomena, examine experience and develop propositions. They are a useful means of developing grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) in new areas of interest.

Knowledge

The possible need to distinguish between data, information and knowledge was suggested above. In the 1960s and 1970s, many workers devoted considerable time and energy trying to define information and proposing distinctions from data. Delineation was not always easy or helpful and different disciplines brought alternative characterizations. Where computer science and management science converged, data was (or were) perhaps seen as events or entities represented in some symbolic form and capable of being processed. Information was the output of data that was manipulated, re-presented and interpreted to reduce uncertainty or ignorance, give surprises or insights and allow or improve decision-making. However, it was perhaps for many, but not all, safer to leave conceptualization and definition of knowledge to philosophers and to recognize that knowledge was potentially an even more complex phenomenon than information.

This is not to say that workable definitions and taxonomies were beyond us. For example, mathematical theories of communication (Shannon and Weaver, 1962) were found to be helpful in delineating levels of information processing. Micro-economic analyses of uncertainty (Knight, 1921) were insightful in relating information to decision-making, and epistemology (Kuhn, 1970) potentially provided some discipline in thinking about knowing. And as data processing and MIS advanced, we at least became both conscious of, and largely comfortable with, the differences, similarities and ambiguities of data and information.

In the late 1970s and the 1980s developments in artificial intelligence, expert systems, intelligent knowledge-based systems and their complementary challenges of knowledge engineering and symbolic representation and manipulation have perhaps likewise stimulated us to reassess knowledge. Indeed the very hyperbole and confusion surrounding these technologies and techniques have demanded some conceptual classification. Now we are at least conscious of the difficulties as the challenges of these branches of computer science have become apparent and so again we can be tolerant of the conceptual murkiness.

This paper does not seek to resolve these mysteries! However, to propose knowledge as a strategic resource, some conceptualization is required. And these two case studies do perhaps demonstrate some interesting—or at least debatable—attributes of knowledge.

We should perhaps first separate knowledge from intelligence. At the everyday level we observe that knowledge can be acquired whereas intelligence is more elusive. The two are connected; intelligence is required to produce knowledge and in turn knowledge provides a foundation upon which intelligence can be applied. Those who have worked in the area of artificial intelligence (AI) generally argue—in the spirit of this lay observation—that AI is concerned with formal reasoning and thus needs to not only represent evidence symbolically but build inference mechanisms employing techniques from pattern recognition to heuristic search, presumably falling short at inspiration and serendipity. AI, like intelligence itself, is essentially generic, general purpose reasoning and easily hits constraints of physical and social complexity. In the context of this chapter, however, as suggested later, the concept of designing and building more intelligence into organizations is not rejected.

Knowledge in contrast—and to be equally “lay” or trite—is what we know, or what we can accept we think we know and has not yet been proven invalid, or what we can know. Expert systems developers have preferred often to talk of “expertise” which is commonly defined as knowledge about a particular (specialist) domain (Hayes-Roth, Waterman and Lenat, 1983). These workers point out that experts—and potentially expert systems—perform highly because they are knowledgeable. The appeal of expert systems is that they can codify both established public knowledge and dispersed, often private or hidden knowledge and make it available to a wider set of users. For example, a bank developed expert systems for lending in order to capture the hard-won credit and risk analysis capabilities admired of loan officers about to retire and thereby be able to disseminate it to young successors and collapse a 40-year training curve. Indeed at Skandia, the intent was the spreading of underwriting skills and experience from senior to junior underwriters and from country to country. Expert systems essentially codify and arrange such knowledge into if … then rules.

One source of knowledge for these rule-based systems is “science,” the published, tested definitions, facts and theorems available in textbooks, reference books and journals. However, experts develop and use expertise which go beyond this. They develop rules of thumb, assimilate and cultivate patterns, conceive their own frameworks of analyses and make educated guesses or judgments. This is also the stuff of expertise and is another layer of knowledge, perhaps less certain than that we might call “science.” It is more private, local and idiosyncratic; it is perhaps better called judgment. We often pay considerably more for judgment than science. Interestingly, we use analysis and enquiry tools, decision support systems and modeling techniques to develop this layer of knowledge. And these applications have some knowledge in them, based on science or previously discovered working assumptions. They are not performing reasoning in the strict sense because they are application-specific or use limited rationality. But they bring some measure of intelligence to bear on the generating of knowledge.

How does this discussion relate to Shorko and Skandia? We can imagine that the distributed process control system contained—or could contain—rules based on physics and the chemistry of polymer/copolymer relationships. Furthermore, statistical process control parameters were built in to recognize unacceptable deviations and variances together with signals to indicate where intervention or caution were required. There was science and there was judgment.

In Skandia, the core database contained no science. But the surrounding applications and decision support tools contained both rules based on actuarial science and judgment embodied in limits on acceptable risks and prices, or underpinning trends and patterns to indicate probable outcomes, plus procedural rules on data input and access. Indeed a second generation of expert systems was being generated to improve risk analysis. The core of the “platform of know-how,” however, was quite simple; it was the capturing and archiving of all transactions in order not to lose experience from which learning could be gained. Indeed business was bought in order to build a comprehensive experience picture; the value of these in some sense undesirable business transactions was the information content.

We can see the same phenomenon in Shorko. The decision to buy further computer power and the process management system enabled the capturing and archiving not of 32 hours’ data but of a year’s experience for analysis. In other words, experience has value and experience is untapped knowledge. It can also be current, continually updated and often situation-specific. The same was true for Skandia’s reinsurance database. Other companies can do the same thing, but the experience-base will reflect each firm’s particular business strategy.

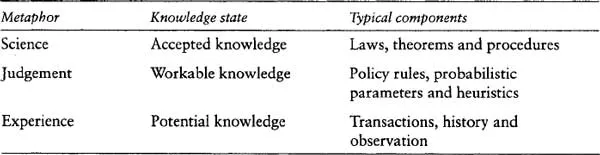

So we can posit three levels of knowledge: science (which can include accepted law, theory and procedure), judgment (which can include policy rules, probabilistic parameters and heuristics) and experience (which is no more than transactional, historical and observational data to be subjected to scientific analysis or judgmental preference and also to be a base for building new science and judgments). This allows us to postulate two models. The first is a hierarchy of knowledge (Table 1.1) where each ascending level represents an increasing amount of structure, certainty and validation. Each level also represents a degree or category of learning. Experience requires action and memory, judgment requires analysis and sensing, whilst science requires formulation and consensus. It will be proposed below that this hierarchy has strategic implications.

Table 1.1 Levels of Knowledge

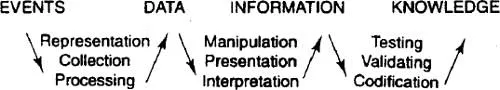

This classification could be argued to be synonymous with the distinctions between data, information and knowledge. The lowest level is the equivalent of transaction data (and transaction processing systems). The middle level is the equivalent of information in the classical sense of reducing uncertainty to make decisions (and thus equivalent also of decision support systems). The highest level is knowledge where use is constrained only by its availability or the intellect to exploit it (and thus approximate to the classical expert system or what some call intelligent knowledge-based systems). This mapping of one taxonomy on another allows us to derive another model, Figure 1.1, which attempts to describe the differences between data, information and knowledge.

Figure 1.1 Towards Conceptualizing Knowledge

In the cases of Shorko and Skandia the core systems could be seen as no more than data. Skandia’s decision support system inventory and Shorko’s reskilling of operators into data analysts were converting data into information. However, both businesses were basing their competitive strategy on understanding their operations on chosen territories better than their rivals. Their goal was a knowledge capability: for Skandia “the platform of know-how,” for Shorko “we didn’t know enough about the process.”

Strategic Value of Knowledge

What do these two cases tell us about the strategic value of knowledge? Both investments yielded strategic advantage; in Skandia this strategy was intended, at Shorko it was discovered—or it emerged using Mintzberg and Waters’ term (Mintzberg and Waters, 1985).

At Skandia, the value of their know-how has been put to the test in two ways. First they will buy business transactions to capture th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction to the Resources for the Knowledge-Based Economy Series

- Introduction to Knowledge in Organizations

- 1. Knowledge as Strategy

- 2. Knowledge of the Firm: Combinative Capabilities, and the Replication of Technology

- 3. Informal Networks: The Company Behind the Chart

- 4. Top Management, Strategy and Organizational Knowledge Structures

- 5. EPRINET: Leveraging Knowledge in the Electric Utility Industry

- 6. A New Organizational Structure

- 7. Tacit Knowledge

- 8. Learning by Knowledge-Intensive Firms

- 9. Organizational Memory

- 10. Cosmos vs. Chaos: Sense and Nonsense in Electronic Contexts

- 11. Financial Risk and the Need for Superior Knowledge Management

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Knowledge in Organisations by Laurence Prusak in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.