- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Navigating Cross-Cultural Ethics

About this book

Through the personal stories of managers running global business, this book takes an inside look into the dilemmas of managers who are asked to make profits ethically according to the dictates of their company's ethics code. It examines what companies `think they are doing to help managers in those situations and how those managers are actually affected. Thanks to the boost from the 1991 Sentencing Guidelines which minimizes penalties for companies with ethics codes caught in ethical wrongdoing, more than 85% of US companies and two thirds of all Canadian companies and half of all European companies now have Codes of Ethics. Yet, over and over, we hear of stories of personal dilemmas and conflicts experienced by individual managers navigating those business waters in other cultures

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Navigating Cross-Cultural Ethics by Eileen Morgan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Scanning for Dragons

“Ethics is a barrel of worms.”

…REP. OMAR BURLESON (D-TEX.)

I was sitting in a meeting in Moscow recently, working with a Fortune 100 company. A large group of Russian, Ukrainian, and American managers were trying to work through some of the communication and operational difficulties they encountered in trying to put together joint ventures in several types of businesses. I had been working in Russia with several clients on a variety of projects since the beginning of perestroika and had recently published a book, co-authored with a Russian psychologist, on the topic of sociocultural barriers that hindered Russians and Americans in working together. Many of the issues being discussed, both rationally and quite emotionally, were issues with which I was familiar first hand.

My Russian colleague in the room was at that time director of the International Business School of Moscow, a new type of institution that seemed to be sprouting up in Moscow as rapidly as the fast food chains that had begun to appear in the ancient streets of the Arbat and Red Square. Every Russian I met in those days described himself as a “biznez” man. The Russians have no word of their own that accurately describes the dynamics of free market trade and capitalism. Until those chaotic, heady days of revolution, the very word biznez was the lowest of epithets, flung in the face of an adversary at the emotional fever pitch of an argument. It was shorthand communication, implying that the party on the other end of the insult was utterly corrupt, and wholly unredeemable.

Andrei, my colleague in this session, was cut from a different cloth. The program he directed, the International Business School of Moscow, was a product of the Ministry of Trade training school aimed at the elite corp of Russians picked to engage in trade and diplomacy outside the old Soviet Union. It had recently been named as the leading choice among Russian business schools by the Wall Street Journal, a highly coveted recommendation at a time when many former Russian entities were relabeling themselves as biznez schools. Andrei, trained in the west in business practices, was now a lecturer every summer at the Harvard Business School and the University of Virginia Darden School of Business. He traveled frequently and freely in the west, particularly the United States. He was intelligent, articulate, and engaging.

We had been asked to speak together during one of the sessions. I spoke about the “baggage” (the mindsets, assumptions, and cultural and business orientations) that Americans bring when working with Russians. Andrei spoke about the “baggage” Russians bring when working with Americans. At this particular moment he was speaking about the Culture of Corruption, a term he had coined, a culture embedded in the very fabric of the Russian culture. He suggested plainly, even offhandedly, that Americans and other westerners must expect that whomever they are dealing with in Russia is, or would be, on some level, corrupt. “I have engaged in it,” he stated casually. “We all have. It’s a fact of life here.” Having spent time before in Russia working with government ministries and their officials, I had a good sense of what Andrei was trying to convey, and I was not particularly surprised by it. I had come up against the types of behavior used to make something happen in Russia, behaviors that seem questionable, inconvenient, or even nonsensical at times. Andrei’s seemingly straightforward comments, however, had a decidedly different effect on the other American managers.

The room erupted with angry comments and questions. “How can you possibly say that?” said one American woman who was quite agitated. “That’s just not true!” denied another man, as angry Americans took exception to Andrei’s comments. They had met, the Americans stressed, many helpful, good, caring people in Russia who were not corrupt.

Andrei tried to explain what he was saying to help them understand what was happening in their business interactions so they could understand and learn how to deal with the consistent undercurrents of corruption. The session ended in bedlam. A hasty break was called to calm tempers with some strong Russian tea.

As I sat there thinking about the scene I had just witnessed, I began to suspect that the Americans were upset about the casual way in which Andrei talked about corruption as a way of life, as if he didn’t think it was such a terrible thing in itself. The Americans were obviously personalizing to actual individuals they knew or had met the behaviors about which he spoke. They did not seem able to reconcile the two sets of information being presented: the individuals they knew personally and his flat assertion that all Russians were part of a Culture of Corruption.

For 15 years I have worked as an organizational consultant in large companies, many of them with international groups and clients. I am used to the struggles that groups go through to be heard and understood as they try to communicate across boundaries of geography and culture. But something different was going on. Americans were trying to persuade a Russian that what he was saying about corruption and ethics from his own cultural point of view was not accurate.

They were saying these things at the same time that some Americans were complaining bitterly that unlike their competition with whom they went head to head everyday, they were not allowed to pay any bribes (or “permissions” or “facilitating payments”) to the local manufacturers to win the contracts to get their airplane engines and locomotives built on site from imported U.S. components. They were not allowed to do this, they said, because of the company’s strictly enforced ethics policy. They were, they stated resentfully, forced to walk away from the table and turn these lucrative deals right into the hands of their competitors, who apparently were not hamstrung by strict corporate ethical policies. They certainly did not want to behave unethically themselves, they reassured me, but they were clearly angry and distressed by this conflict: the conflict between doing business and making profits—what they had been sent here to do—and the company’s ethics policies, which prevented them from doing what was necessary to function in Russia.

As I sat in my chair on the dais watching the agitated clusters of company representatives file out of the room, I thought about other instances in which I had felt the tension of individuals charged with conducting business overseas profitably but faced with obstacles in conducting it ethically. Logistical and administrative transactions that Americans take for granted in getting through the day became moments of truth. Merely trying to get packages or parts delivered, paperwork completed, and staff recruited, hired, and trained could generate the “oh-oh” feeling (a wonderfully useful and descriptive phrase taught to me by a friend who teaches self-defense to children). Whether it was dealing with banks and agent organizations in Cairo while developing a new Suez canal toll payment product or faced with parts delivery problems in which “a small favor” (like finding a job for the niece of the local customs agent) could go a long way toward expediting the transaction, I learned to recognize the cost of transgressing ethical norms and the cost, both real and perceived, of staying within them.

When it comes to running a business in another culture—or with suppliers, vendors, or customers from other cultures—the simple rules for getting things done, with which we in the United States are familiar, simply don’t always apply. The very process that we define as “getting things done” looks different in Moscow, Madras, or Milan than it does in Milwaukee or Mobile. Straightforward business transactions such as placing orders, shipping goods, generating documentation, or socializing with customers become colored by different ideas about accomplishing business or the importance of interpersonal and long standing relationships. The confusion and emotion around ethics in cross-cultural transactions was evident in the room with the Russians, Ukrainians, and Americans. I have heard similar expressions of confusion and frustration while working with managers in India (both Indian and U.S. managers) and Latin America. In management courses at some of the leading corporate management education institutions in the world, the ethical dilemmas of doing business across cultures frequently come up.

WHAT ARE WE TALKING ABOUT WHEN WE TALK ABOUT BUSINESS ETHICS?

The tension between how we know we ought to behave as individuals and corporate citizens and what actually goes on in day to day practice is clearly illustrated by the level of cynicism and dark humor that accompanies the topic. As managers and citizens we shake our heads at the practices of some high-profile investment traders, both here and around the world, who are responsible for stealing millions of investors’ dollars. We are enraged at oil conglomerates trying to walk away from accountability and billions of dollars of damages caused by mismanaged vessels. We are appalled at careless disregard for human life and safety in countries where the regulations that exist are not enforced strictly or at all. We decry the national scale of corruption evident in stories coming from Italy, India, and Malaysia. It only takes reading the newspapers to understand the personal and organizational tension that exists around ethics.

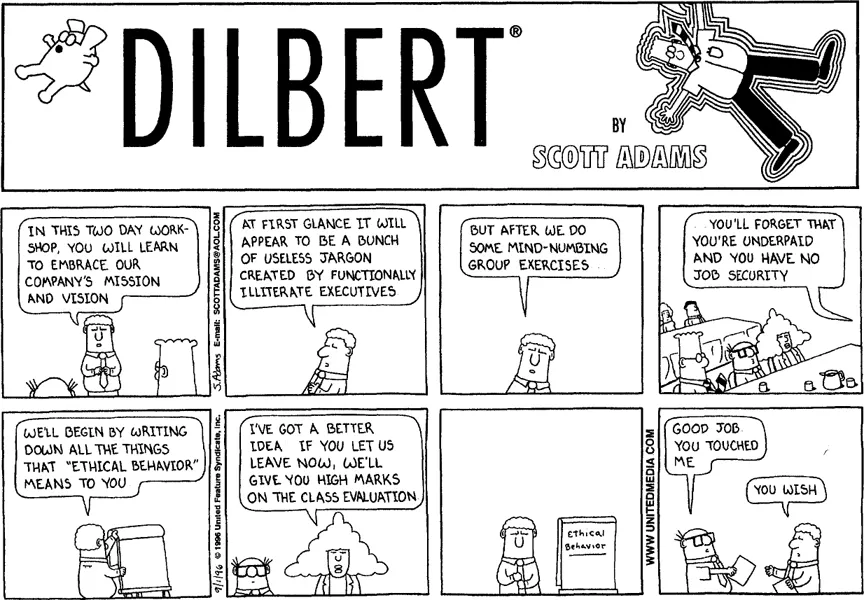

The subversive chief social commentators of our day, the cartoonists, hit the subject regularly and with deadly accuracy. Scott Adams, creator of the brilliant and wildly popular comic strip Dilbert, zeroes in on the commonly dismissive notion of business ethics being “mostly common sense.”

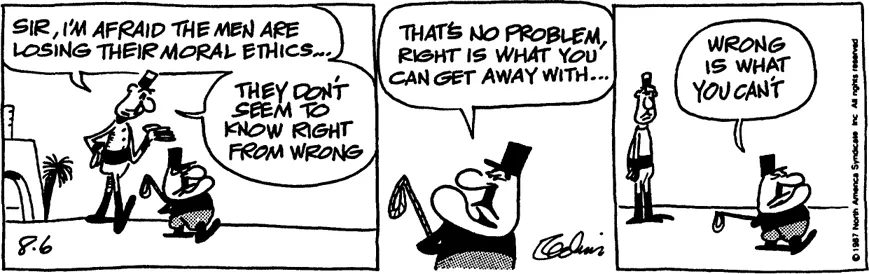

Gary Trudeau, creator of the long running Doonesbury strip, regularly skewers the ethical practices of Wall Street, focusing, as do Bill Rechin and Don Wilder in their strip Crock. Rechin and Wilder also contend in their strip that the convenient although cynical working definition of ethics is “Right is what you can get away with. Wrong is what you can’t.”

Figure 1.1 Dilbert 9/1/96 reprinted by permission of United Feature Syndicate, Inc.

It is easy to stay cynical, to throw our hands up in the air or shrug our shoulders and sigh resignedly that it’s all too complex. It is easier to give in to our “inner cynic”and say that business ethics is an oxymoron. The kind of dismissive attitude that conveys “We’re all in this together and ain’t it awful,” is easier, but it’s no longer responsible or smart. This book is about why managers can no longer afford that dismissive attitude and what they can do to change that attitude in their company.

Figure 1.2 Crock Cartoon 8/6/87 Right Is What You Can Get Away With. Reprinted with special permission of North American Syndicate.

What Is the “It” We Are Trying to Get Away With?

Albert Z. Carr, in his now famous Harvard Business Review article “Is Business Bluffing Ethical?” (1968) suggested that if business is nothing more than a game, as many of its players insist, then business ethics are simply the sleights of hand and bluffing techniques that go along with knowing the rules of any game, such as poker. One must be able to divorce one’s personal morality from what is right and wrong to win the game.

Trying to reach a working definition of business ethics becomes even more of a challenge when we place it in the global crossfire of values, judgments, and agreements about what is morally right behavior. The age-old question, “Whose values?” surfaces again—and often. One of the things that clouds our ability to speak clearly about business ethics is that we try to cover a vast territory of meanings, attitudes, philosophies, values, and behavior with just one word, ethics, not unlike what we have been trying to get away with for centuries by using the single word love to convey a spectrum of meanings, acts, and relationships.

Very recently I worked with The Chautauqua Institution, this country’s oldest institution for adult education, moderating a weeklong series of dialogues and discussions under the title The Business and Ethics Forum. On each of four days, staff, managers, and sometimes union representatives of a well-known company were invited to discuss with an audience of 200 people an ethical dilemma of their choosing they had faced or were facing. These ethical dilemmas were presented as “live cases” in which the individuals from the company who were actually involved in the situation presented the situation to the participating audience. Each live case was presented from the perspectives of the shareholder, the organization, the community, the union, and other groups in the company who were affected by the situation. After a brief presentation of the dilemma, as defined by the company, from the perspectives of management, employee, shareholder, and community, the audience was invited to think through the same issues in small groups and react to the company representatives with questions, challenges, and issues. The discussion was lively, passionate, intelligent, emotional, and frequently loud. Underlying each company’s discussion each day was the wide array of topics that were considered ethical dilemmas. None of these dilemmas specifically addressed issues in doing business globally, so the reader can see how difficult it is to talk about these issues, even in the context of our own culture. Here’s a look at the spectrum that emerged. (Each company that participated in the forum requested its name be held confidential. I found this to be true of many individuals with whom I spoke.)

“Look What You’re Doing to Us”

Located in a small upstate New York town, it was clear to Glassco, Inc., that the future of the business lay in investing heavily in its fiber optics business, which was growing tenfold, and away from the classic consumer products business for which the company was known by name worldwide. In the town of 30,000 that was home to corporate headquarters, the company employed 10,000 persons. Fully 10 percent of the company’s employees worldwide were employed in the consumer products business. Whereas the company had made a commitment to build the new fiber optics plant in the same town as the corporate headquarters, the talent required in this high-tech business would not be readily available from the town. It was clear that jobs being lost in the consumer end of the business would not be replaced by townspeople in the new fiber optics business.

THE ETHICAL DILEMMA: Is it ethical for a company to change its line of business so completely that it is has a dramatic effect on the small community to whom it has provided jobs, livelihood, and millions of dollars in community resources?

“You Have No Right to Do That!”

The second day’s ethical dilemma was presented jointly by the plant manager and union president of Truckcom, an international automotive company. This small rural company had been the target of five takeovers in 4 years and was still losing money. The company was heavily unionized and had most recently come under non-U.S. management. The new management felt hamstrung by its inability to work through the issues necessary for revitalization and productivity. The union contract prohibited the new management from hiring outside the company for the skills and talent they believed they needed. In an eleventh-hour rescue, the foreign management team decided to leave the plant open but ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Epigraph

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 Scanning for Dragons

- Chapter 2 The Rising Storm of Business Ethics in Global Organizations

- Chapter 3 Fate and Free Will: Meaning and Mirage

- Chapter 4 Creating a Map for Your Ctoss-Cultural Ethical Navigation

- Chapter 5 Journeying with Your Ethical Map

- Chapter 6 Charting the Course Through Leadership

- References

- Appendix I

- Appendix II

- Appendix III

- Appendix IV

- Appendix V

- Index