![]()

Korea in the World

England knows nothing of Korea. Yet Korea is worth knowing. It focuses so many problems, focuses them so clearly.

H.B. Drake, Korea of the Japanese (1930)1

Korea today exemplifies the possibilities and contradictions of globalization to a degree matched by few other places in the world. Two separate states, both products of the Cold War, confront each other on the Korean peninsula with the threat of mutual destruction long after the Cold War's end. One is an isolated, impoverished, heavily armed, and highly nationalistic Marxist-Leninist regime; the other is a burgeoning liberal democracy and emerging advanced economy deeply embedded in global networks of political, economic, and cultural interaction and integration. Coming out of a common history, culture, and ethnic identity, the two Koreas have responded to the challenge of globalization in radically different ways: North Korea appears to have resisted the global capitalist economy almost to the point of self-destruction, while South Korea is often seen as the twentieth century's most successful example of a third-world country benefiting from globalization to achieve advanced industrial status. Yet, contrary to conventional wisdom at the end of the Cold War, the successful economic and political development of South Korea, in stark contrast to the dismal economic performance and political atavism of North Korea, has not led to the absorption of the latter into the former, along the lines of German unification. North Korea, despite the enormous suffering of its people in recent decades, has proved remarkably resilient. By the early twenty-first century North Korea had begun tentatively opening up its economy to the outside world, yet it is still ruled by the same family and political party under which the country was founded in 1948. South Korea, especially after the financial crisis of 1997 poured cold water on its economic “miracle,” has rejected the German model of unification by absorption as far too expensive and disruptive for its own interests. The two Koreas may be with us for some time to come.

As any cursory glance at the map will reveal, Korea is situated at the nexus of strategic interest among the world's most militarily powerful states (the United States, China, and Russia) and between the world's three largest national economies (the United State, China, and Japan). South Korea itself is the world's twelfth largest economy, and North Korea, despite its poverty, has one of the world's largest armies and a growing nuclear weapons program. Potential site of international war or national unification, victim of famine and major exporter of advanced technology, the Koreas are an ideal vantage point from which to observe and understand contemporary global trends and processes. In analyzing the world's impact on Korea and Korea's impact on the world, this book will consider the shifting and multiple meanings of “Korea” in contemporary history: a geographical entity, an ethnic nation, two states since 1948, and an ethno-cultural identity extending beyond the Korean peninsula to include substantial minority communities in China, the United States, Japan, and the former Soviet Union. We will seek to understand Korea's place in the world through a rigorous and historically grounded analysis of the meaning of globalization in this specific locale. While various forms of global integration have existed for millennia, the speed, scale, and depth of contemporary (post-1945, and especially post-1973) economic, political, and cultural transformations do indeed represent a new form of worldwide interconnectedness.2 In many ways, Korea is an exemplary site for examining these transformations. For example, the migration of Koreans abroad–equivalent to 10 percent of the population of the peninsula–and the emergence of two Korean states are both products of Korea's sometimes difficult encounter with modern globalization. Divided and diasporic Korea thus forms a useful lens through which to view the modern transformation of our increasingly globalized world.

Globalization and Korea

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, “globalization” had become a nearly ubiquitous term in scholarly and popular discourses, in fields ranging from economics to international relations to cultural studies. South Korea (the Republic of Korea, ROK) in the early 1990s even established an official “globalization policy” for the country under the slogan segyehwa (literally “world-ization,” something like the French mondialisation), promulgated by then-President Kim Young Sam.3 Inevitably, such widespread usage has led to numerous and diverse definitions for this term. One of the most useful and concise definitions of globalization may be found in David Held et al., Global Transformations:

Globalization can be taken to refer to those spatio-temporal processes of change which underpin a transformation in the organization of human affairs by linking together and expanding human activity across regions and continents.4

By this definition, globalization is nothing new; such processes have existed since the beginning of human civilization. What is new is the rapid acceleration and intensification of these processes in the last one hundred years, and especially the last fifty.

Placing Korea in world-historical time, we can see that Korea has fared differently according to different periods of globalization. If we follow Held et al. in historicizing globalization into pre-modern (to 1500), early modern (1500–1800), modern (1850–1945), and contemporary (since 1945) periods, it is evident that Korea did rather well in the first two periods. Early modern Korea, that is, the Chosŏn dynasty (1392–1910), was for much of its history a stable, peaceful, and relatively prosperous state by world standards. But Korea clashed disastrously with forces of modern globalization from the mid-nineteenth century onward. In the last half of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, Korea lost its traditional security and trade relationship with China, declined economically and disintegrated politically, and was colonized by Japan in 1910. Liberation from Japanese colonial rule in 1945 resulted in joint Soviet–American occupation of the peninsula, leading to the creation of two separate states in 1948; this was followed in short order by a brutal civil war (1950–1953), which, because of Korea's position in the newly emerging Cold War, drew in the United States, China, and (indirectly) the Soviet Union. The war concluded with an armistice that left Korea divided, a situation that persists to this day.

Over more than half a century of separation, the two Koreas have developed into radically different political, economic, social, and cultural systems, locked in fierce competition with one another. During that time, however, their relative positions in the world system have shifted dramatically. If we divide the period of post-World War II contemporary globalization at about the mid-1970s, a key point of rupture and transformation in the global economy–the end of the gold standard, the OPEC oil shocks, the beginning of the high-tech revolution–it becomes clear that until that point, North Korea was well ahead of the South economically, as well as much more stable politically. From the mid-1970s onward, however, the South developed rapidly and soon overtook the North. By the mid-1990s the gap had grown overwhelmingly in the South's favor, and the ROK had entered the ranks of advanced industrial economies while North Korea faced a crisis of famine and de-industrialization.5

South Korea, deeply integrated into the world system, flourished despite the setbacks of the late 1990s. North Korea, claiming stubborn adherence to a policy of juche, or self-reliance, staved off catastrophe largely through foreign assistance.

Thus, while Korea as a whole was undeniably a victim of modern globalization, the two Koreas since 1945 have had quite different experiences with new forms of global change: North Korea did relatively well in the first phase, South Korea did much better in the second, post-1973, phase of contemporary globalization. It is important, however, to place the more recent experience of the two Koreas in the history of Korea's overall experience of modernity since its mid-nineteenth century encounter with Europe, America, and a rising Japan, in order to understand why the two Koreas dealt so differently with the modern world. While the forces the two Korean states have had to deal with are universal, the means of dealing with them are in some ways distinct to Korea, and come out of Korea's very specific history. By the same token, the endgame of divided Korea may be quite unexpected to those who assume Korea will follow a straightforward Western path. Along the way, it is important to discard, or at least examine very critically, the widely held perception (held not least by Koreans themselves) that Korea has always been the helpless victim of foreign powers and interests.

Korea's Collision with Modernity, 1850–1953

Korea is often understood to be the natural and perennial victim of its location, a small nation caught between the rivalries of larger neighbors, a “shrimp crushed between whales,” as the Korean proverb puts it. One popular study of contemporary Korean history recounts that “Korea has suffered nine hundred invasions … in its two thousand years of recorded history.”6 This is a dubious reading of Korean history, for several reasons.

First, not every attack on the Korean peninsula in recorded history can be considered an “invasion” of “Korea.” The establishment of Chinese-controlled garrisons in the northwest of the peninsula around the time of Christ cannot be seen as offenses against Korean sovereignty, as there was no such unified political or cultural unit as Korea until long afterward. In later centuries, pirate raids originating from the Japanese islands (not necessarily conducted by natives of those islands) were disruptive to life on the peninsula, but were hardly wars of conquest.

Second, compared to many other areas of the world, including much of Europe as well as other parts of East Asia, what is remarkable about Korea's history is not the number of foreign invasions, but Korea's ability to maintain internal stability and political independence over such long periods of time. If the number of attacks by foreign entities determines the degree of a state's “victimization,” then China, which was conquered more often and attacked far more frequently than Korea before the twentieth century, would be the greater victim. Indeed, in the thousand years from the beginning of the Koryoŏ dynasty in the tenth century to Japanese colonization in the twentieth, there were only three full-scale attempts by outside powers to conquer Korea: by the Mongols in the thirteenth century, the Japanese in the late sixteenth century, and the Japanese again in the early twentieth century. Only the final attack succeeded in eliminating Korean sovereignty. The Mongols made Korea a tributary of the Yuan dynasty but did not absorb Korea into their empire. The Japanese invaders of 1592–1598, led by the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi, were defeated by a combined force of Korean defenders and their Ming Chinese allies, although not until after the Japanese had laid waste to much of the peninsula. The Manchus of the Northeast Asian mainland also attacked Korea in the early seventeenth century, but in order to force the Korean king's shift of allegiance from the Ming to the Manchu (Qing) dynasty as the legitimate rulers of China, not to conquer Korea. It took Japanese colonization in 1910 to erase Korea's independent existence, for the first time since the peninsula had been unified in the seventh century. Few states in Asia, to say nothing of medieval and modern Europe, can claim such a record of continuous integrity and independence.

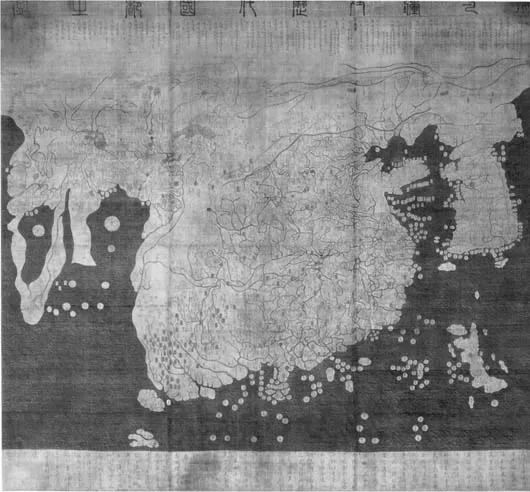

The third and most important reason that it is misleading to read Korea's history as a history of victimization due to the peninsula's unfortunate location, is that such a view ignores the historically contingent nature of geographical significance. Geography is never a “given,” as spatial conceptions change with time.7 Locations only become “strategic” at certain conjunctures of power, knowledge, and technology. For most of their history, Koreans did not at all see themselves as inhabiting a small peninsula strategically situated between rival Great Powers. A Korean map of the world in 1402 ad, for example, shows a large and centrally located China, flanked by a Korean peninsula only slightly smaller, and a tiny Japanese archipelago almost off the edge of the map (see Figure 1.1). This exemplifies the “classical” Korean view of Korea's place in the world for over a millennium: China as the central civilization, Korea nearly coequal with China, and Japan small and insignificant.

What changed at the end of the nineteenth century was the emergence of a new nexus of power, knowledge, and technology that gave rise to a stronger and more assertive Japan, and ultimately reduced Korea and China to colonial or semi-colonial status. This was a new way of envisioning and controlling the world's spaces, first articulated in Europe (especially England and Germany) and later adopted enthusiastically by the Japanese. It was a Prussian military

Figure 1.1 Korean map of the world, 1402 AD.

advisor, Klemens Wilhelm Jacob Meckel, who originally suggested to the Japanese government in the 1880s that Korea was “a dagger pointed at the heart of Japan.”8 For Japanese leaders of the Meiji era (1868–1912), the Korean peninsula was of new and vital strategic importance, and had to be kept out of the hands of geopolitical rivals–first China, then Russia. This sense of geopolitical rivalry on the part of the Japanese, the desire to control spaces that might otherwise come under the domination of competitors, is quite different from the desire to drive through Korea to become emperor of China, which had motivated Hideyoshi in the 1590s. Korea, in short, fell victim to the rise of geopolitics in the final quarter of the nineteenth century.9 It was at this point that Korea became a “shrimp among whales,” a vortex of Great Power conflict. Korea was the central focus of two wars in the decade surrounding the turn of the twentieth century: the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. Japan won both wars, and annexed Korea in 1910.

If peace, stability, and political integrity are considered positive attributes, then Chosŏn dynasty Korea was a remarkably successful polity. The dynasty itself lasted for more than 500 years, from 1392 to 1910. Although there have been symbolic monarchies that have lasted longer–the Japanese imperial family, for example, claims a rulership of 2000 years, but for much of that time the emperor was a powerless figurehead in Kyoto–no other actively ruling monarchy since, perhaps, ancient Egypt has remained in power as long. But the longevity of Korean kingship is more impressive than the Chosŏn dynasty alone: the transition from the previous Koryoŏ dynasty (918–1392) to Chosŏn was not a radical break, but a relatively smooth transfer of power that retained most of the institutional structure and a large part of the elite personnel from one dynasty into the next.10 No significant interregnum or civil war separated the two. In short, the traditional Korean “political system” existed almost unchanged, with only minor adjustments, for almost exactly 1000 years.

What explains this remarkable stability and longevity? Stability does not equal stagnation. Korea did change over time, and in the seventeenth century underwent a significant rise in commercial activity, centered around the ginseng and rice merchants of the former Koryoŏ capital of Kaesŏng. But social and economic change did not lead to drastic changes in the political system, or in Korea's relations with its neighbors, through much of the second millennium AD. Internally, the Korean monarchy and bureaucracy were able to adjust themselves to each other in a rough balance of power, and to keep under control an occasionally restive, predominantly peasant population.11 The Korean social structure, highly stratified and unequal like most agrarian societies in history, managed to function fairly well and with few internal threats; until the nineteenth century, violent, large-scale peasant rebellions were much less common in Korea than in China or Japan. As for Korea's external relations, after the disaster of the Japanese invasions, Chosŏn kept foreign interaction to a minimum. But even before that, Korea's interactions with its neighbors were less than vigorous by Western standards. Korea's relations with the outside world, which meant primarily China but included Japan and “barbarian” groups in Manchuria, drew maximum advantage at minimum cost. Japan was kept at arm's length, primarily for trade relations, with a small outpost of Japanese merchants residing in the area of Pusan and occasional diplomatic missions via the island of Tsushima. Chosŏn exchanged envoys three or four times a year with China and gave lip service to Chinese suzerainty, but for the most part acted independently. Barbarians to the North were generally kept in check, with Chinese assistance, or absorbed into the Korean population. As for the rest of the world, Koreans had no use whatsoever. Those few Westerners who happened to land on Korean shores, such as Dutch sailors shipwrecked on Cheju Island in the seventeenth century, were treated with respect and curiosity but were not seen as sources of any important kno...