![]()

| VI | Curriculum and Instruction |

![]()

| 12 | Fractions: A Realistic Approach |

L. Streefland

State University of Utrecht

Realistic can be misinterpreted easily. Obviously its first meaning signifies that the mathematics to be taught is linked up firmly with reality, or rather in reverse: reality serves both as a source of the envisaged mathematics and as a domain of application. This chapter contains the description of four building blocks for a course on fractions. All of them reflect this aspect of realistic albeit at different levels. Moreover fractions can evolve as a mathematical reality for the learners in this way. This means realistic also refers to the manner in which the learners realize (their) fractions in the teaching-learning process. For bridging the gap between concrete and abstract they need to develop tools such as visual models, schemas, and diagrams. These are the vehicles of thought for students that enable them to enter mathematics and to make progress within it. An extended description of a long-term, individual learning process illustrates this. It reflects the attempts to integrate the processes of teaching and learning fractions. This is what developmental research will result in: courses that deal with both teaching and learning.

Mathematicians from Klein to Freudenthal and psychologists like Piaget and Davydov have concerned themselves explicitly with the educational problem of learning about fractions. Many others have continued to address the challenge represented by fractions in mathematics education (Hilton, 1983; Usiskin, 1979). In the context of the current concerns regarding education, it is time to focus attention on those questions about fractions in mathematics education that are of primary importance in learning to think mathematically.

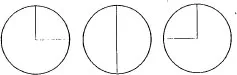

Moving at once from the general to the specific, the following number sentences present an ideal starting point for discussion:

Let us relate each of these number sentences to a bar of chocolate containing six parts. Half a bar equals three parts and two parts equals

. If three parts and two parts are combined, just one part or

is missing. Thus,

. Similarly, the difference between one half and one third of a bar can be determined by comparing three parts with two parts, which leads to

.

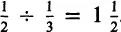

For

the partitioning is done in stages. Of the two parts representing one third of the bar, one half of one part must be taken, which means

=

. Finally, for the division, the result can be derived from comparing the three parts with the two parts. This shows that the last one fits one time and a half in the first one, so

.

Thus, by means of a mediating representation (e.g., the bar consisting of six parts), the main operations of fractions can be perceived and performed. Establishing meaning is one of the most important concerns, both historically and currently, in the teaching and learning of fractions.

How do children acquire an understanding of the meaning of fractions? To answer this, an overview of the research and development that has been done over the last 10 years in The Netherlands is provided. The next section examines the question of how fractions acquire their meaning by presenting two building blocks for a course on fractions: the activities of fair sharing, and seating arrangements in fair-sharing situations (see Streefland, 1991, for a complete description). In the following sections, other building blocks are reviewed. Relevant reflections and theoretical issues based on the view of fractions in Freudenthal (1983), Streefland (1984, 1986, 1991), and Treffers and Goffree (1985) are considered. An example of one student’s learning process, which took place over a 2-year period, is described and analyzed with respect to one of the most important features of the acquisition of the concept of fractions, namely, yielding to or building up resistance to N-distractors.

Fractions: How Do They Acquire Meaning?

Two activities, fair sharing and splitting up the group of sharers into subgroups, are used to illustrate our learning activities. In the situations that resulted from these activities, fractions acquired meaning as mathematical objects. What happened in the aforementioned analysis is that

the column of number sentences was taken for granted because this is what the author intended, as was the case for the bar of chocolate with six parts. The same can be claimed for the symbolic building blocks used to express both fractions and operations. Are we to suppose, for instance, that the symbols for both numbers and operations for fractions have the same meaning as they have in the context of natural numbers? When children treat them that way, like

, why is this not correct, and how can we make the distinction clear to the learners?

The Activity of Fair Sharing

Let us begin with an example: “Divide 3 pizzas among 4 children.” Each child will get three fourths of a pizza, providing the sharing is done fairly. The portions can be described by means of linguistic tools that later will be called fractions. First, the learners estimate their answers. “Does each person get more or less than a half?” Upon hearing more, the pupils can begin to distribute half-pizzas, and then figure out what to do with the rest. Fractions that are closely linked to repeated halving

can be used as

points of reference for estimation. It is preferable that the students themselves choose such reference points for estimation rather than having these references offered by others (Streefland, 1982).

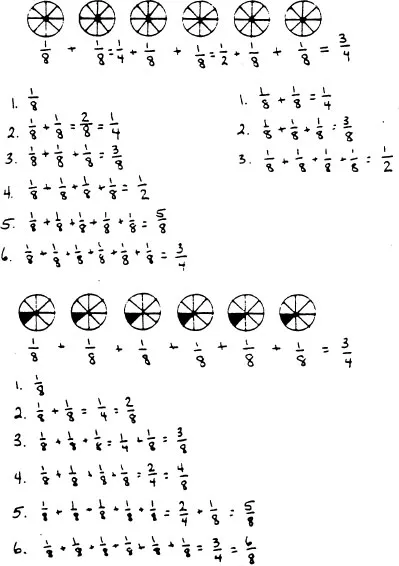

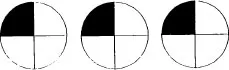

One by one:

Everyone gets

, which is

, or

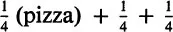

First two, then one:

Everyone gets

(pizza), and later

more:

, or

.

All three at once:

Two children get

, and two children get

.

It is striking that in fair sharing as a varied source for the production of fractions the concept of fraction and the informal operating with fractions are directly related to each other. In this kind of approach, it is impossible to constitute mentally the part-whole aspect of the fraction without also becoming involved in insightful or rules-anticipating operations. When attaching a measure, weight, or price to what is being distributed, the fractions then take on the function of an operator.

Our example of fair sharing illustrates a compound process of division, informal operating, and abbreviating. The following representations express this symbolically:

Comparison of the first and third line shows that two fourths are hidden in one half and so on. That is, what was already visible in the drawn material now can become anchored mentally and symbolically—namely, that

\ is what has been called a

pseudonym for

or

(or the other way round).

Equivalent Fractions

Exploration of situations such as “Divide 6 pancakes among 8 children” and “5 pizzas among 4 children” produces equivalent fractions and mixed numbers. Consider, “Divide 6 pancakes among 8 children.” Class members’ impressions during our teaching experiment are quoted (Streefland, 1991).

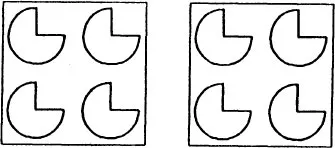

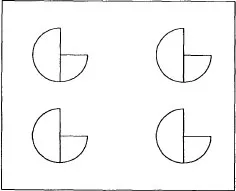

Frans drew the following figure on paper and wrote that this was the same as three pancakes for four people, only “Now it’s doubled”:

Margreet still needed the support of names, and called the sharers “1,2,…, ” She used these symbols to indicate the pieces each person received and drew the following:

Marja wrote: “First each one gets a half and then a quarter.” Kevin used his paper actually to distribute pieces. He distributed the pieces of each pancake systematically and fairly to 8 dishes by drawing connecting lines.

The students’ earlier experiences dividing 3 pizzas among 4 children were called upon. Five students divided the pancakes exclusively into fourths, and 11 students made halves and fourths. No one divided them into eighths.

Because of the previous results, it was judged necessary to pay attention to the unit-by-unit division and to describe the outcomes of the process successively, as well as in intermediate stages of the sharing process. The problem was based on the story of a French restaurant where the pancakes were served this way: The first pancake is served and divided among the sharers, so is the second and so on —a process pupils called French division. This activity produced a good deal of what we termed monographic material, as is shown by the two examples of pupils’ work in Fig. 12.1.

Fig. 12.1. Examples of student work for the problem of dividing 6 pancakes among 8 children.

All the children were quite familiar with repeated halving and its description up through and also with the related mutual conn...

Everyone gets, which is

Everyone gets, which is , or

, or

Everyone gets(pizza), and later

Everyone gets(pizza), and later more:

more: , or

, or .

.

Two children get, and two children get

Two children get, and two children get .

.