- 495 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introduction to Building Management

About this book

This is the classic practical introduction to the broad principles of building management. It is suitable for both students and practising construction professionals who are concerned with greater efficiency within the construction industry.As a general textbook for the student, the introduction covers the entire field in some depth providing a firm foundation for additional reading. The text is closely geared to the chartered Institute of Building (Member) Parts I and II examinations. The book includes examples based upon and related to working experience. It will also be found valuable by students reading for the examinations of other professional bodies in the construction industry, and by HNC/D students.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Introduction to Building Management by D. Coles,G. Bailey,R E Calvert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Ingénierie de la construction et de l'architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

——— Part 1 ———

Introduction

——— Chapter 1 ———

The Meaning of Management

In this book the term management refers to the philosophy or practice of organized human activity, whilst managers are the people responsible for the conduct and control of such an undertaking. As the name suggests, management is a social exercise, part art and part science, involving the organization of a number of individuals in order to achieve a common purpose. The manager is therefore concerned with the ways and means of getting a job done, so that management entails responsibility for

(a) planning and regulating the enterprise by installing and operating proper procedures,

(b) ensuring the co-operation of personnel by providing the will to work and guiding and supervising their activities.

The field of management is usually divided into general and specialist branches, for each of which there have been developed particular techniques or ‘tools’, and in each of which a professional institution is to be found. These management functions are broadly common to all industries, and the list below are of particular relevance to the building industry.

(a) Corporate management responsible for the formulation of policy, the discharge of legal responsibilities, overall direction and co-ordination of specialist functions; organization charts and manuals, standard procedures, management ratios, control figures.

(b) Financial management covering the capital and revenue resources, accounting, insurance and costing; budgetary control, cost analysis, cost control.

(c) Design management, traditionally the responsibility of an architect in the building industry but increasingly the management of design in the modern construction industry is seen as the function of the project manager.

(d) Development including experimental work and research into both materials and processes; statistical method.

(e) Marketing concerned with external relations, tendering and the securing of future work; advertising, public relations.

(f) Production management covering the complete process of planning and co-ordinating the work of construction; planning, programming, progressing, materials control, work study, quality control, safe working practices, sub-contract management, communication methods, plant management.

(g) Maintenance directed towards the upkeep of property, transport, plant and equipment; planned maintenance.

(h) Personnel concerned with the employment of labour, manpower planning, recruitment and selection of staff, equal opportunities, induction procedures, training programmes, staff appraisals, disciplinary and grievance procedures, health and safety; industrial relations, welfare provision, payment policy.

(i) Administration responsible for devising clerical and office management procedures and means of communication, the development of computing and information technology-based systems.

(j) Purchasing involving the procurement of services, materials and equipment, delivery and quality control, supply progressing.

The basic fundamentals of management and detailed operation of techniques can be taught and applied for the most part irrespective of the industry concerned, and, despite the special problems and differences of emphasis of the construction industry compared with others, building managers should understand and master the principles and methods involved. In addition to technical skill and experience, executives require education and training in management to fit them for present day conditions and the complexities of modern building.

In the following chapters the background, development and application of scientific method to the general problems of industrial management are described in the section Management in Principle. In the section Management in Practice are explained those various management functions that are common to all managers, but viewed from the specific standpoint of the several partners in the building team. The fourth section, Management Techniques, covers those particular management tools that, properly understood and utilized, can help to keep the construction industry abreast of the continually more difficult demands of a changing world.

But we must never forget that managers of businesses are fundamentally concerned in performing two basic tasks-preparing goods and services, and selling them. Thus, whilst there is an urgent need for more effective bridges between theory and practice so that they may enrich each other, we must not allow a too academic or scientific pre-occupation to distract us from the down-to-earth practical aspects of managing building and civil engineering projects.

Some of the most significant management changes of the last 20 years have been brought about by world-wide recessions. The oil crisis of the early 1970s and the deep recession of the late 1980s and early 1990s particularly affected the UK. The consequence of this has been a sharpening of competition and the increased importance of marketing. The last 20 years has also seen increased competition for the UK in the international arena. Competition from Europe, the Far East and in particular Japan, has led to increasing adoption of new management techniques.

Instead of waiting for enquiries to tender for work, it has become necessary to anticipate the requirements of prospective clients, to prepare organizational resources to meet those needs and then go out to sell the services made available. This philosophy today permeates and colours every aspect of management activity.

——— Chapter 2 ———

The Role of Industry in Society

Social responsibility

The industrial manager has obligations to three different social groups:

(a) the shareholders or directors who have appointed him,

(b) the human beings whose labour he manages,

(c) the general community, both local and national.

To his employers a manager has a two-fold responsibility, to safeguard the capital invested in plant, machinery, etc., and to earn profits as interest on money loaned to the enterprise. These fairly obvious responsibilities are discharged by means of various administrative procedures or control techniques, such as accountancy. It must be remembered however, that industrial activities are subject to the same moral code which governs all other aspects of life, so that the manager must ensure that his business policies do not conflict with his other obligations.

With his employees the manager must preserve the dignity of human labour, and determine his dealings with equity and justice. Moreover, work must be arranged so that it requires some measure of initiative and responsibility, in order to provide the worker with social satisfaction and status. Again, the individual's contribution to the total effort must be openly recognized so that pride in work and the creative instinct are given outlets.

Effectiveness and economy of operation must be attained by the promotion of co-operation through the personnel function, by an understanding of the part played by human emotions, and by the provision of improved working conditions. Finally, the manager must inculcate in his workers a sense of their own responsibilities, for effective results require the combined efforts of both capital and labour. The manager's obligation to his employees can be summed up as the promotion of their happiness and contentment, or morale.

From the community, management has received labour, materials and amenities, and hence owes a responsibility to supply goods or services of the right quality at reasonable prices. This involves an obligation to ensure the maximum utilization of the undertaking's productive potential, and the most effective use of its resources, in order to satisfy the current needs or desires of the community and to maintain a proper balance between the various consumers. To the local community, the manager must recognize his responsibility to provide suitable and regular employment for the citizens, and to respect or improve the physical and social amenities of the district, when considering such matters as waste disposal and building design.

Some of these latter obligations are not so immediately obvious, or require such a high level of competence, that this particular field is a good example of the need for training for management.

The demands of society

The ever-changing economic climate, major environmental concerns, Britain's membership of the European Community, the demand that organizations should be socially responsible, and the insistence that the whole decision-making process in business be shared, have led to much new thinking about the purpose of industry in society.

The frontier discussion meeting on ‘Industrial Growth and the Demands of Society’ held in 1973 by the British Institute of Management (BIM) was announced as follows:

The last decades have seen a remarkable growth of the economies of the industrialised areas of the world, but resulting affluence has brought its own problems. Social demand, for example in relation to education, health, urban renewal, transportation, housing and environment, is becoming the major claimant for public investment in most of the ‘developed’ countries and could easily absorb all the products of increased economic growth to be expected in the present decade. In addition, problems of scale and excessive centralisation of government activity is producing in many affluent societies an increasing alienation of the individual, with difficult manifestations which range from apathy to violence. As prosperity grows, aspirations become generalised both within and between countries, leading to strong currents of equalitarianism. Technological development, on which growth of the economy depends, is increasingly distrusted, especially by the young, and social environmental obstruction of plans for power stations, nuclear reactors, pipelines and oil refineries may well delay general solutions of the energy problem. These matters are of deep concern to industry and necessitate much rethinking in terms of long-term self-interest; they demand also a new type of relationship between industry and government in which can be seen to be contributing more directly to the attainment of national goals.

It is interesting to observe that the problems outlined above are still the major problems facing the industrial world today. This is shown by the continuing problems of the coal industry in the UK as opposed to other forms of energy generation for electrical power. Transportation policy in the UK, including the proposed privatization of the rail network, the planning problems associated with new motorways and major road improvement schemes, the channel tunnel fast rail link to London and the continued social concerns with health and education still dominate agendas.

The role of industry

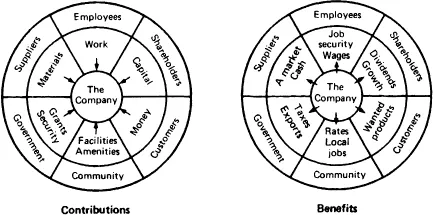

The business situation is illustrated in the diagrams (see Fig. 2.1) where six groups exert pressure on a company, each offering a contribution, and each deriving benefits to satisfy its particular needs. All groups – government, community, customers, shareholders, employees and suppliers – share a common interest that the enterprise will continue and grow, so that they will share in the increased prosperity. No group therefore can afford to be too greedy, and hence a dynamic equilibrium is established between the contenders, based upon a controlled conflict of interests. Only one group (the employees) is in touch with all the others; hence they must hold the balance although they are an interested party. In a company all up to and including executive directors are employees, and must share in the arbitration role. Since the end of the 1939–45 war, governments have attempted to take over this role, by price, wage and dividend restraints, and this distortion has damaged both industry and commerce, and inhibited growth and investment. In latter years the trend has been for government to distance itself from private industry in some of these areas. However, government fiscal policy relating to interest rates and taxation can still have severe effects upon industry. In the 1990s, the UK membership of the European Community will result in many more European directives affecting industry.

The function of profit

Britain enjoys a mixed economy, where private enterprise and public authorities operate side by side in the national interest. Industrial enterprises such as manufacturing, construction, agriculture and quarrying produce the required goods, and commercial institutions like insurance, banking and building societies provide the necessary services. This is the wealth-producing sector that funds the Welfare State, our cultural life and all the advantages of a advanced technological civilization. This small overcrowded island of necessity must import a large part of its food and raw materials, and our balance of payments is dependent upon both the visible and invisible exports of industry and commerce. Monopolies and restrictive practices are controlled by legislation, whilst free competition ensures that failure to maintain an output greater than the input leads to liquidation or bankruptcy.

FIG. 2.1. The role of industry in society (after A. C. Hutchinson)

Central and local government, health authorities and centres of higher education, are supported wholly or in part by taxation or rates levied upon private individuals and corporations. Nationalized industries and public utilities are required to be profitable and produce a modest return on their investments, but there is no similar penalty for failure. Their monopolistic positions allow them to raise prices unrestrainedly despite user councils, or else to demand subsidies from the taxpayer. The measure of success in a capitalist society is of course profitability, and boards of directors are responsible to their shareholders for keeping the company solvent and ensuring an acceptable return on their capital. But in both private and state-owned companies employees must appreciate that their living standards and their security of a good life are equally dependent upon the successful management of productive enterprises. Similarly, executives, supervisors and workpeople must understand that profit is a real and necessary condition for the survival of every company. Provided that a business is run in socially acceptable ways (more of this later), profits are a guide to efficiency, a sound test of performance and a stimulation to management morale. Profit may also lure capital onto untried trails, so that research and invention are encouraged, and innovation rewarded. It is no coincidence that the French word for contractor is ‘entrepreneur, for the construction industry is truly the epitome of private enterprise.

Profit is what is left after all costs and overheads have been deducted from the price or contract sum. Being also the product of turnover multiplied by the profit margin, it is difficult to increase overall profit by maximizing the one without damaging the other component. Since the would-be entrepreneur must provide the correct product/service, at the right time, at a price that the market is prepared to pay, maintaining the optimum balance is a constant preoccupation of the commercially minded manager. Moreover, there are other more subtle factors such as reputation and public responsibility (e.g. safety) which must be fulfilled to ensure long-term profitability.

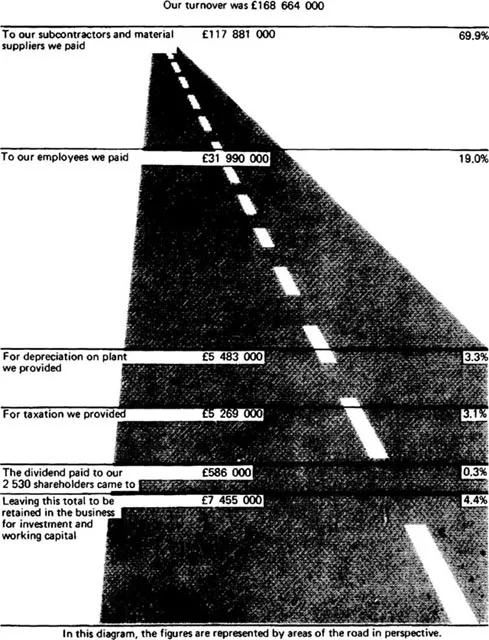

Much of the present-day controversy surrounding profit is not about the making but the distribution. Examination of the public accounts of almost any sizeable company will show that the shareholders receive a modest return on their risked capital, whilst the lion's share goes to the government in taxes, and what is left is necessarily ploughed back into the business to furnish new investment. A typical example is shown in Fig. 2.2.

FIG. 2.2 Where does the money go? (from Sir Alfred McAlpine Group of Companies Report to Employees 1977)

Perhaps the cause of much dissatisfaction lies in the apparently insoluble desire to combine maximum personal liberty with a continue...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface to Sixth Edition

- Revisers’ note

- Preface to Fifth Edition

- Preface to Fourth Edition

- Preface to Third Edition

- Preface to First Edition

- Part I Introduction

- Part II Management in Principle

- Part III Management in Practice

- Part IV Management Techniques

- Appendix 1 Terms used in CPM

- Appendix 2 Metric conversion factors

- Index